What "history is written by the victors" misses

A short saying is no substitute for the scrupulous study of the past

“Good talk…” the visitor would say to me.

“Here comes the ‘but,’” I would think to myself.

“But you know, history is written by the victors.”

Conversations like that happened to me on occasion when I worked as a guide and historical interpreter at several historic sites. I could typically see the signs before I even finished my talk, tour, or program. The visitor would spend most of my presentation frowning with their arms crossed. It was clear that they disagreed with much of what I was saying, but they didn’t want to challenge me during the program. After I’d finished speaking and the crowd started to disperse, they'd approach me, say, “history is written by the victors,” and walk away, often before I had a chance to respond.

While people disagreeing with you is part of the job when you’re interpreting the past, I did regret that these visitors almost never seemed interested in having a conversation about the aphorism they used to try and rebut me. If they had been willing to talk, we could have discussed how “history is written by the victors” is a phrase that simultaneously speaks to important considerations but also oversimplifies and distorts the work of historians and the field of history.

He who controls the past…

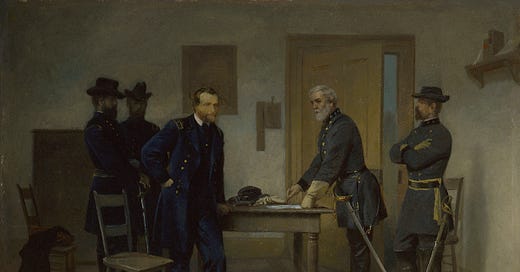

Sometimes, the visitors acted as though they were the ones who coined the saying, but there’s a good amount of debate on who first said “history is written by the victors.” Winston Churchill, Hermann Goring, and various historians have all been incorrectly credited with originating the maxim, but the true answer will probably never be known.1 Its origin is less important than its impact. Throughout the centuries, the phrase has been deployed by thinkers, artists, politicians, and historians. A scene from The Simpsons is seemingly inspired by it. One episode shows a Civil War reenactment at “Fort Springfield,” where the guide informs the crowd that the Union garrison was “too brave” to accept the surrender of a group of tired, sick, and defeated Confederates. As the Union reenactors “kill” the Confederate reenactors, the announcer declares to the cheering audience, “The brave Springfielders heroically slaughtered their enemies as they pleaded for mercy.”

While played for laughs, The Simpsons clip highlights that there is some truth to the idea that “history is written by the victors.” History, the study of the past, is based on the examination of sources. If Side A triumphs, it stands to reason that we’ll have more documents from them and few, if any, accounts from Side B. Likewise, individuals with power in society are more likely to have their sources preserved, while sources relating to historically marginalized groups are more likely to be destroyed or discarded, either accidentally or deliberately. Throughout the human story, victors in wars and other conflicts have portrayed their actions as noble and good, while their vanished enemies are portrayed as brutal monsters. The narratives created by both government officials and many past historians often whitewashed what had actually occurred, turning murders, massacres, and other atrocities into feats of glory. This is a well-established concern for historians, and any good history program will emphasize the need to understand how both the sources we have and the sources we don’t can shape the works of history we produce.

“Fort Springfield” is fake, but there have been many massacres throughout history that were whitewashed into heroic victories. In 1864, the Cheyenne chief Black Kettle led his band to a camp at Big Sandy Creek in present-day Colorado. Tensions between American settlers and the local Indigenous nations were high, but Black Kettle hoped to avoid bloodshed and had been in communication with government authorities to ensure the safety of his band. Unfortunately, Colonel John Chivington had other ideas. Despite Black Kettle flying both an American flag and a white flag over his camp to show that his band was not a threat, Chivington and his soldiers attacked, murdering over 230 people.2 In his report, the colonel did not describe how he slaughtered unarmed children but instead spun a tale of how his soldiers triumphed against a well-armed foe.3 Chivington’s account was reprinted, and he and his soldiers were treated as heroes.4

So, were the people who confronted me on my tours correct? Did my talks lack value because “history is written by the victors?” Given the preceding paragraphs, what’s my concern with the phrase? Who writes history if not the victors?

How to lose a war, thousands of your soldiers, and then be raised to secular sainthood

By the end of 1865, the Confederate States of America was dead. Its armies had been decisively defeated, its railroads had been torn up, and many of its factories had been burned to the ground. The Thirteenth Amendment had outlawed the hereditary, racialized, chattel slavery Confederate leaders had fought to defend. Hundreds of thousands of soldiers had gone off to fight for the Confederacy only to never come home, losses that would be felt in their homes and communities for decades. The Confederacy had so definitively lost the war that diehard Confederate Edmund Ruffin committed suicide rather than live under the US flag again.5

Yet, within less than a century, the Confederate cause had been valorized and mythologized. Statues of Confederate leaders stood in many southern cities, military bases bore the names of Confederate generals who had waged war on the United States, and textbooks and popular media throughout the USA valorized the Confederate cause as a heroic but futile struggle to defend slavery states rights. The novel Gone with the Wind, which presented an idealized depiction of the antebellum South, was a sensation upon its publication, and its film adaption remains the highest-grossing movie in American history when adjusted for inflation.6

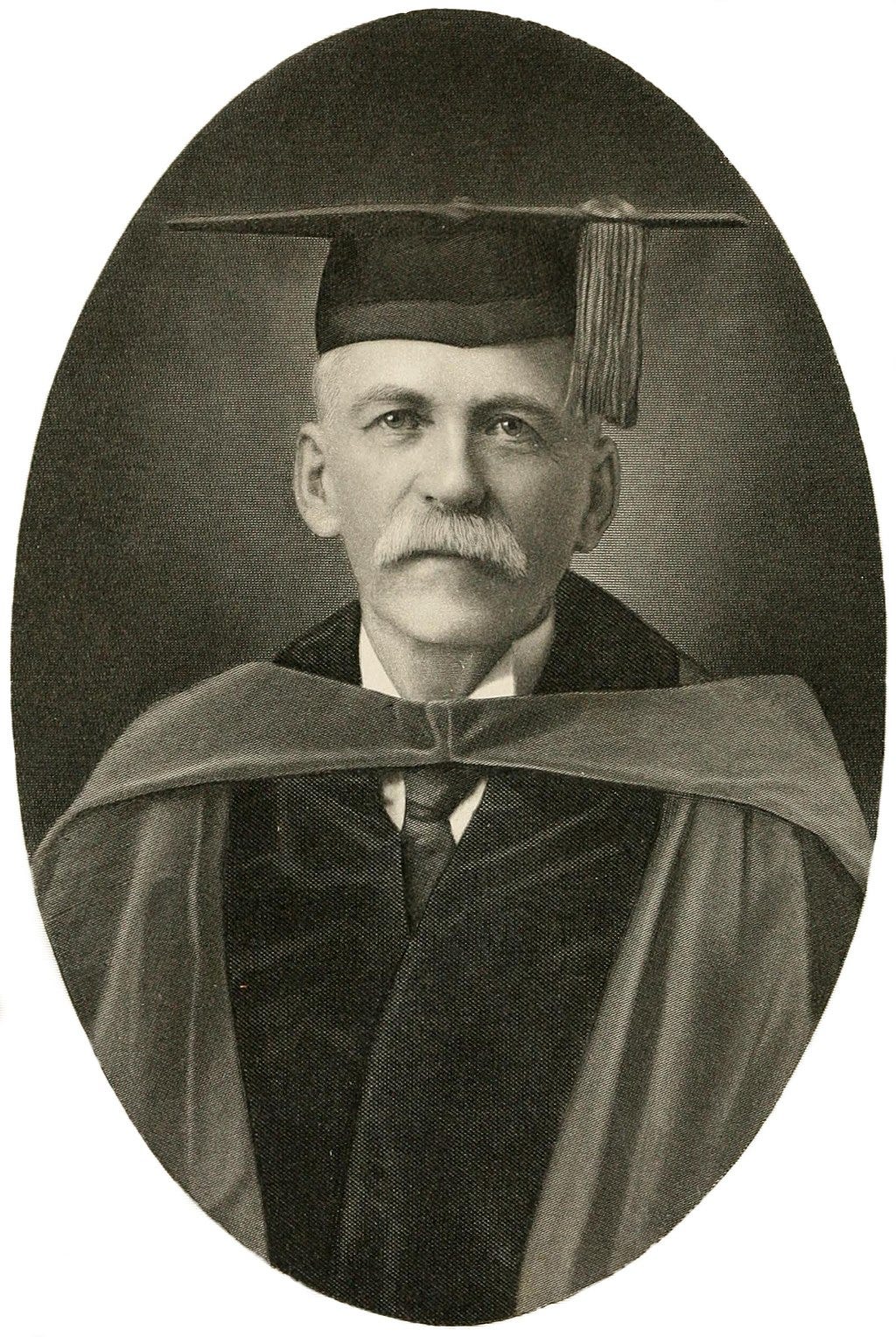

I’m far from the first person to note how the story of what became known as the “Lost Cause” challenges the “history is written by the victors” adage. In his article, “Bad Historical Thinking; History is Written by the Victors,” historian and National Park Service ranger Nick Sacco notes, “There may be no stronger example of ‘losers’ writing widely accepted historical narratives than those who have advocated for the Lost Cause interpretation of the American Civil War.”7 As Sacco describes, “In the years after the Civil War, Lost Cause advocates grabbed their pens and their pocketbooks in an effort to win the memory battle over the meaning of the nation’s bloodiest conflict.”8 Former Confederates wrote books that emphasized their heroism and deemphasized slavery as the central cause of the war. Organizations like the Sons of Confederate Veterans and the Daughters of the Confederacy erected monuments and worked to influence the content of textbooks to present a pro-Confederate interpretation. Confederate leaders like Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson and Robert E. Lee were held up as heroes, while Union leaders like Ulysses S. Grant were dismissed or degenerated. Historians at major universities promoted the Lost Cause narrative. Professor Lyon Gardiner Tyler at the College of William and Mary wrote what became known as “A Confederate Catechism,” which lays out many Lost Cause principles.9

To be sure, former Confederates had been able to reclaim some power in the aftermath of Reconstruction, using Jim Crow laws, sharecropping, convict leasing, and voting restrictions to economically, politically, and socially oppress Black Southerners. Still, even if you consider the ex-Confederates “victors” at a regional level, that doesn’t explain the success of the Lost Cause outside of the South. Growing up in Pennsylvania in the 1990s and early 2000s, I was exposed to Lost Cause mythology. In history class, we learned that slavery was wrong and that it was the central cause of the war. However, through conversations with various adults (and in a couple of English classes), I definitely heard many tenets of the belief, including “the war was solely about state’s rights” and “Lee was the epitome of a general, Grant was a drunk.”

Given that I‘m writing this critique, it’s clear that the Lost Cause does not have a monopoly on historical thinking. Counterarguments began as soon as the first former Confederate put pen to paper. Union general George Thomas, a Virginian who stayed loyal to the Union, noted, “Everywhere in the States lately in rebellion, treason is respectable and loyalty odious.”10 Frederick Douglass, who self-liberated himself from slavery, noted in a speech at Arlington Cemetery, “We are sometimes asked…to remember with equal admiration those who struck at the nation’s life and those who struck to save it…We must never forget that victory to the rebellion meant death to the republic.”11 While some historians embraced the Lost Cause, others firmly rejected it. Works by historians like John Hope Franklin, James McPherson, Elizabeth Varon, Bruce Levine, Gary Gallagher, and others have used extensive documentation to rebut the Lost Cause narrative.

What do we mean when we say “victor?”

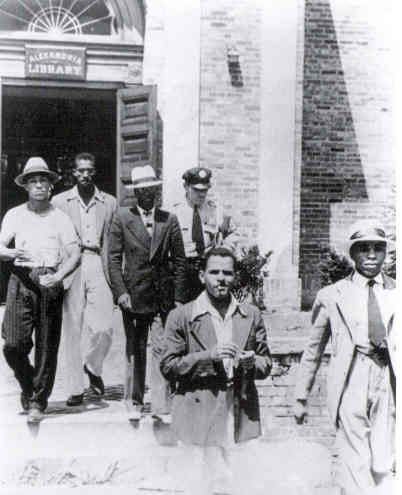

In his article, Sacco notes that “winners” “is a vague and ill-defined term in this context.”12 “Vague and ill-defined” hits the nail on the head when we talk about “history is written by the victors.” How do we determine a victor/winner in the broad scope of human history? As an example, in 1939, Samuel Tucker led a sit-in protest to desegregate the local library in Alexandria, Virginia. The demonstration was only partially successful; the library did not desegregate, but the City of Alexandria grudgingly built a separate facility for Black Alexandrians. Tucker, who led the protest, didn’t consider this a victory and refused to use the new building on principle. The city’s library system didn’t fully desegregate until the 1960s.13 So who was the winner here?

On the one hand, Tucker and his allies eventually achieved their objective, albeit several decades later than they had hoped. Local racists were probably infuriated that they had lost the battle for a segregated library and now had to share the facilities with all residents. On the other hand, the Black population of Alexandria in the 1960s continued to face economic injustice, racism, and a lack of political power at the hands of the white power structure, so Tucker probably didn’t consider himself fully victorious as many challenges remained.

The question of who is a “winner” in history gets even more complicated when one looks at the international space. Taken literally, “history is written by the victors” would imply that, after the American Revolutionary War, only the Americans could write history. But why? After all, the British Empire had not been dismantled and would only grow in size and power over the next century. It’s not as though George Washington could storm Kew Palace and point a pistol at George III’s head if the king attempted to write down his account of events.

Going even further back, the Egyptian Pharaoh Ramesses II had his scribes and artists commemorate his victory over the Hittite Empire at the Battle of Kadesh in 1275 BCE. As a successful pharaoh who led one of the most powerful states in the Bronze Age, Ramesses could certainly be considered a “winner” in the grand scope of history, and he had the resources to write down his version of events. However, Ramesses didn’t win at Kadesh. In fact, historians believe that, at best, the battle was a tie, and at worst, the Egyptians lost. That didn’t stop the pharaoh from writing his version of history and declaring himself the victor. The Hittites, although victorious at Kadesh, weren’t powerful enough to impose their version of the past on Ramesses, even though theirs was more accurate. However, Ramesses’ version didn’t survive the test of time. Anyone today who is interested in the battle would be hard-pressed to find a scholarly work that treats the pharaoh’s account as gospel. Ramesses was a “winner” in many ways, and that allowed him to claim that he had won a great victory. However, all of his power couldn’t stop future historians from recognizing the holes in his story and comparing it with the other available evidence.

Want to end up in a history book? Create a source

“My father, now the ships of the enemy have come. They have been setting fire to my cities and have done harm to the land.”14 The line comes from a letter found in the ancient city of Ugarit in modern-day Syria, and archeological evidence indicates that the writers’ fears were well-placed. The city was violently destroyed. However, there remains much we don’t know about its fate, including who “the enemy” was.15 While the City of Ugarit is not a “winner” in the scope of history, thanks to the archeological record and surviving letters, we know a decent amount about it. Who or what destroyed the city remains unclear. It’s been theorized that the “Sea Peoples,” a group allegedly responsible for the destruction of several civilizations during what’s known as the Bronze Age Collapse, might have destroyed Ugarit. However, historians and archeologists continue to debate who the Sea Peoples were and their true impact on the Eastern Mediterranean, as the records relating to them are fragmentary. Whoever sacked Ugarit could call themselves a “victor,” but we know far less about them than the city they destroyed.

A few centuries after the fall of Ugarit, the ancient Greek historian Thucydides wrote his history of the Peloponnesian War, conveniently titled History of the Peloponnesian War. The conflict had seen Sparta defeat Athens, humiliating the proud city-state and stripping it of much of its empire. Today, Thucydides’s writings are a valuable source for historians, in part because so few first-hand textual sources for the conflict exist. But Thucydides was not a victorious Spartan. He was an Athenian general who not only was on the losing side of the conflict but had been exiled from Athens after commanding a failed military expedition during the war.16 Given this, It’s hard to call Thuycides a “winner,” but in one sense, he did better than most of his Athenian and Spartan counterparts. He was able to write his account of what happened and, in doing so, shape future understanding of the event. Like all historical sources, Thucydides’s account has its biases and omissions, but his version of the war remains with us because he wrote it down, and future generations preserved it. Not bad for a disgraced general from a defeated power.

The study of history is based upon analysis and comparison of sources. The more sources we have, the more we can know about a past person, society, or era. To be sure, this gives an advantage to history’s “victors.” The rich and the powerful are more likely to be able to create sources that reflect their views and ensure they’re preserved. However, that doesn’t mean that our only sources are from history’s “winners.” Sometimes, as in the case of Ugarit or Thuycdides, the opposite is true. Furthermore, as we’ll discuss later, historians have many tools to parse sources, identify gaps, and read between the lines to piece together stories.

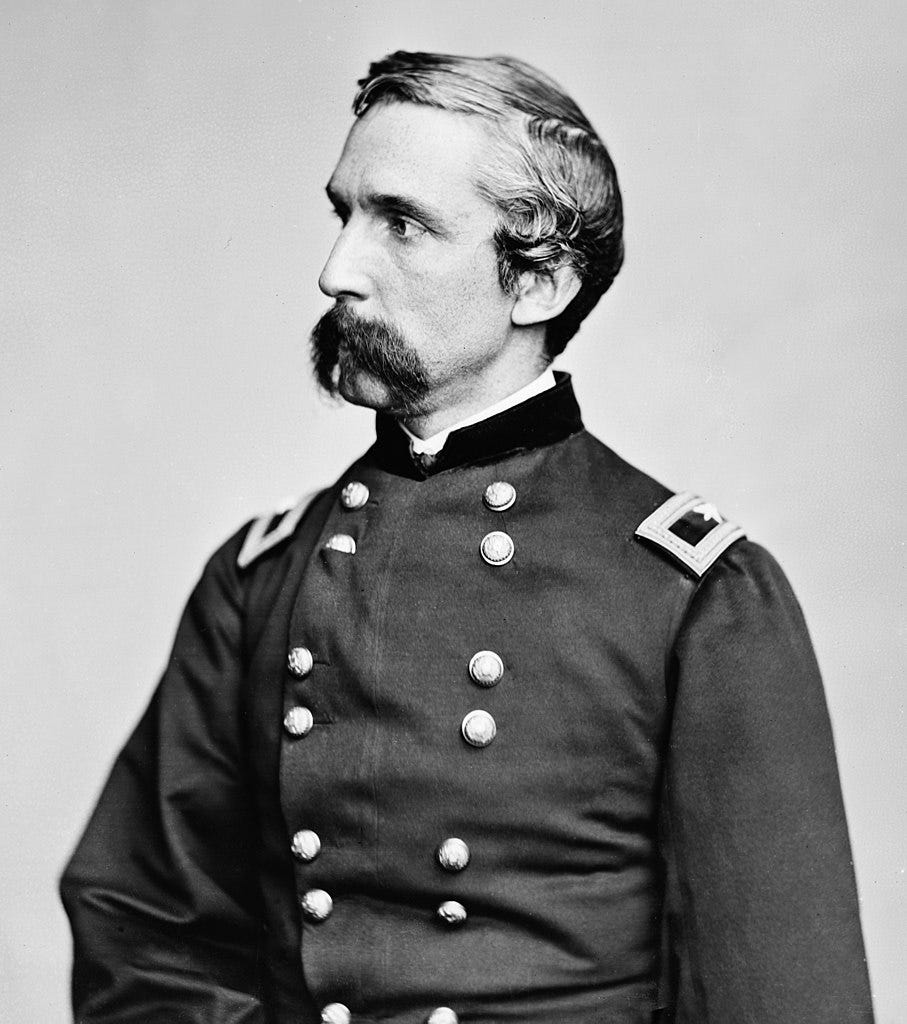

Creating historical narratives isn’t just a competition between opposing sides. Sometimes, historians have to parse through differing accounts from people on the same side of a conflict or movement. On July 2, 1863, during the Battle of Gettysburg, Colonel Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain helped defend Little Round Top, a key part of the Union Army’s position, by ordering a bayonet charge against advancing Confederates. After the war, Chamberlain wrote his memoirs of the conflict. Thanks in part to these printed recollections, Chamberlain and the 20th Maine achieved almost mythic status, with some arguing that they single-handedly saved the Union cause on that hot July day.

Historians over the past few decades have pushed back on this narrative, noting that the actions of many Union commanders and units helped stop the Confederate advance on July 2nd.17 That is not to say that the 20th Maine’s actions weren’t brave and valuable to the Union cause or that Chamberlain’s writings are not a useful source. Rather, the full picture reveals a larger story in which the regiment’s actions were one part of the successful defense of the left flank of the Army of the Potomac.

So why did Chamberlain get all the glory compared with the other commanders on Little Round Top? Why didn’t they write their own memoirs? This dialogue from the movie Gettysburg, although fictional, illustrates the reason:

The 20th Maine has faced several rebel attacks. Many of the soldiers are dead and wounded. Colonel Chamberlain receives reports from his officers that ammunition is running low. A soldier runs up with news of the other Union regiments nearby.

Soldier: Would like to report…

Chamberlain: What? What? What?

Soldier: Colonel Vincent is badly wounded. Yes sir, got hit a few minutes after the fight started. We’ve been reinforced at the top of the hill by General Weed’s brigade up front, that’s what they tell me. But Weed is dead. So they moved Hazlett’s battery and artillery up there. But Hazlett’s dead.

It’s hard to write a memoir when you’re dead. Chamberlain survived the battle and was able to tell his story. Many of his fellow commanders on Little Round Top that day weren’t so lucky. Chamberlain, Hazlett, and Weed were all on the winning side, but Chamberlain was the only one who lived long enough to put pen to paper. In that sense, history is written by those who can create a source before their time on this earth is up.

History isn’t static, and historians weren’t born yesterday

The historical method is the act of research, analysis, communication, and revision. The work of a historian is never-ending, and what we believe to be true about the past today might no longer be the case twenty years in the future. Historians are constantly reexamining old beliefs, adding additional layers of nuance to the historical record, and considering new sources and new types of sources. The dynamic nature of history is something that “history is written by the victors” does not account for. Rather, it implies the opposite: that the victors write the history, and historians simply regurgitate the information again and again until the end of time.

Source analysis is a key part of the historian’s job, and understanding the bias of various records and narratives is part of the training historians go through. Historians know that people have reasons to distort the truth, and so part of their research is determining what information can be gleaned from a source and what information needs to be taken with a small (or large) grain of salt. In the past half-century, historians have worked to look at sources in new ways to provide more information about people and communities that were often overlooked or marginalized in the past. Mary Thompson in The Only Unavoidable Subject of Regret and Bruce Ragsdale in Washington at the Plow both utilized George Washington’s personal journals to learn more about the enslaved community at Mount Vernon. However, the books they’ve written are not whitewashed accounts that treat Washington as a benevolent enslaver. Rather, because both historians are skilled at reading between the lines, they can create a picture of the enslaved community that endured Washington’s punishments, worked to resist his orders, and, in a few instances, even outwitted or escaped from the first president. Neither historian accepts Washington’s writings at face value, and they also utilize other sources to add additional context and perspectives. While both books are of great value to historians, Washington himself probably wouldn’t be too happy with some of their conclusions.

Returning to the Sand Creek Massacre, today, the site of the murder is managed by the National Park Service. Rangers there work for the same government that Chivington did. However, visitors hear a very different story than the one Colonel Chivington wrote. While Chivington presented a heroic battle where his men overcame steep odds, the park’s website calls his actions “the barbarism of November 29th” and condemns his legacy, bluntly informing web visitors that “the Sand Creek Massacre stands as a testament to a brutality that should be learned from and never repeated; a lesson of what the rejection of conscience in the face of fear and hysteria can lead to, and the suffering that this betrayal has imparted on generations of Arapaho and Cheyenne people.”18 This rejection of Chivington’s narrative is reflected in the very name of the site. It’s not called the “Sand Creek Battlefield” or “Sand Creek National Military Site,” but “Sand Creek Massacre National Historical Site.”

So, how did Chivington’s account fall out of favor? Cracks immediately appeared in the aftermath of the slaughter. Several soldiers in Chivington’s regiment were horrified by what had happened and reported it up the chain of command. A Congressional committee called it a “foul and dastardly massacre.”19 Still, Chivington’s version of events endured. A 1909 monument to Colorado soldiers called the massacre a battle.20 However, Cheyenne and Arapaho survivors of the massacre and relatives of the dead kept the memory of what happened alive, which eventually prompted more and more historians to analyze the flaws in Chivington’s story and examine the sources that contradicted his account. The existence of the Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site today reflects the research efforts by historians as well as sustained involvement by the Cheyenne and Arapaho leaders and community members. This process isn’t linear. A History Colorado exhibit about the massacre from a few years ago was criticized for inaccuracies, but even then, the scholarly activities of historians and efforts by stakeholders eventually compelled the organization to create a more accurate exhibit.21

Competing interpretations and debating ideas about the past are part of the historical method. For many years, the popular image of Reconstruction, the time period after the Civil War, was one presented by Gone with the Wind and Birth of a Nation, which focused on the sufferings of white Southerners after the war and the corruption of Northern officials. While many historians endorsed this view, others, including W.E.B. Du Bois, pushed back. Du Bois and others highlighted the civil rights gains of the time period, the establishment of public schools for both white and Black children throughout the South, and other achievements. They also emphasized the violence inflicted by white Southerners on Black southerners and their allies. Over time, through the work of historians like Kenneth M. Stamp, Eric Foner, and others, this understanding of Reconstruction has become widespread in the academic world. While many in the public still think of Gone with the Wind when they think about the post-Civil War period, documentaries like PBS’s Reconstruction: America After the Civil War and the creation of Reconstruction Era National Historical Park all testify to the growing public reexamination of Reconstruction.

How the public perceives the past

“History is written by the victors” presupposes that there is one historical narrative that the public receives. Is everyone getting the same information about the past? No. People learn about the past in different ways, as this report by the American Historical Association discusses. One person’s knowledge of the Tudor Dynasty might come from reading a recently published book by a reputable scholar, another might read a book that’s out-of-date, while still another might get their understanding from watching The Tudors.22 People might also receive different versions of the past as they go about their lives. As I noted earlier, although I got whiffs of the Lost Cause growing up, I still learned slavery was the main cause of the Civil War. Go to one historic plantation, and you’ll get an accurate depiction of the brutal realities of slavery. Go to another, and you’ll get a “Moonlight and Magnolias” version of the past, which presents an inaccurate view of everyone being happy and there being no conflicts until the Yankees arrived.

Are there books, museum exhibits, and other works of history communication that deserve revision, whether due to overreliance on sources created by the powerful or for other reasons? Of course. Sometimes relevant sources are overlooked, sometimes the set of sources one has is very limited, and sometimes historians make mistakes about which sources to trust. But here’s what’s often forgotten by the public. Revaluating our historical knowledge is part of the process. It’s a feature, not a bug. I’m sure that some of the research products I’ve created during my career will become out of date as new sources and new information come to light, and I’m okay with that. Our understanding of the past is constantly evolving, and the dialogue between historians, stakeholders, and the public means that discussions about history will continue into the future.

Why learn history when you have a one-liner?

I cannot speak for everyone who uses the phrase, “history is written by the victors,” but I can discuss the motivations of those who used it to try and rebut my public programs (often, but not always, when I talked about slavery and the Civil War). By and large, the people who quoted it to me weren’t interested in hearing about my sources. They didn’t want to know more about the documents I reviewed, the analysis I had done, or the work of the scholars I had read. Rather, they wanted to delegitimize everything I had said without doing any research or engaging in the historical method themselves. Using my Civil War talks as an example, since the United States had won the Civil War, these visitors argued that anything historians, rangers, or guides said about the conflict and its causes that challenged their preconceived notions was fake since “history is written by the victors.” All of the primary sources created by the Confederate officials and supporters and the countless hours of research conducted by historians throughout the decades meant nothing. “History is written by the victors” gave these visitors a reason to ignore what they heard and avoid having to reexamine their preexisting beliefs.

That’s the issue with the phrase “history is written by the victors.” At its best, it is a useful tool during the historical method, a way to give the historian pause and consider what perspectives and sources they do not have and what narratives have been promoted or suppressed by powerful people and organizations. At its worst, it is a way to stop the historical method in its tracks. It allows one to avoid the messy, time-consuming, and complicated effort of actually engaging with the human story and instead walk away with a smug sense of superiority, preexisting beliefs intact and unchallenged. When deployed this way, it denies the ability of historians and historic sites to improve their understanding of the past and the information they give the public. It erases the work of historians who have worked to challenge dominant narratives and add nuance to our understanding of previous eras.

History written by the victors does exist, but the way to challenge it is through detailed study, careful analysis, and reasoned arguments, not through tired one-liners.

Matthew Phelan, “The History of ‘History Is Written by the Victors’” Slate, November 26, 2019, https://slate.com/culture/2019/11/history-is-written-by-the-victors-quote-origin.html

“Sand Creek Massacre National Hisotric Site,” National Park Service, Last updated April 9, 2021, https://www.nps.gov/places/sand-creek-massacre-national-historic-site.htm

Tony Horwitz, “The Horrific Sand Creek Massacre Will Be Forgotten No More,” Smithsonian Magazine, December 2014, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/horrific-sand-creek-massacre-will-be-forgotten-no-more-180953403/

Tony Horwitz, “The Horrific Sand Creek Massacre Will Be Forgotten No More,” Smithsonian Magazine, December 2014, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/horrific-sand-creek-massacre-will-be-forgotten-no-more-180953403/

John M. McClure, “Edmund Ruffin,” Encyclopedia Virginia, October 12, 2024.

“Top Lifetime Adjusted Grosses,” Box Office Mojo by IMDbPro, (last accessed on October 15, 2024), https://www.boxofficemojo.com/chart/top_lifetime_gross_adjusted/?adjust_gross_to=2021

Nick Sacco, “Bad Historical Thinking: ‘History is Written by the Victors,’” Exploring the Past, February 15, 2016, https://pastexplore.wordpress.com/2016/02/15/bad-historical-thinking-history-is-written-by-the-victors/

Sacco, “Bad Historical Thinking: ‘History is Written by the Victors.’”

Alison Bell, The Vital Dead: Making Meaning, Identity, and Community through Cemeteries, (Knoxville: University of Tennesee Press, 2022), pg. 136. Dan Monroe, “Lincoln the Dwarf: Lyon Gardiner Tyler’s War on the Mythical Lincoln,” Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association, Vol. 1, no. 1 (Winter 2003), https://quod.lib.umich.edu/j/jala/2629860.0024.104/--lincoln-the-dwarf-lyon-gardiner-tylers-war-on-the-mythical?rgn=main;view=fulltext

Kenly Stewart, “The Anti-Lee: George Henry Thomas, Southerner in Blue,” Emerging Civil War, September 2, 2021, https://emergingcivilwar.com/2021/09/02/the-anti-lee-george-henry-thomas-southerner-in-blue/

Andy Hall, “Frederick Douglass on Decoration Day, 1871,” DeadConfederates, May 27, 2012, https://deadconfederates.com/2012/05/27/frederick-douglass-on-decoration-day-1871-2/

Sacco, “Bad Historical Thinking.”

Brenda Mitchell-Powell, Public in Name Only: The 1939 Alexandria Library Sit-In Demonstration, (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2022), pg. 147.

Eric H. Cline, 1177 BC The Year Civilization Collapsed, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2021), pg. 107

Cline, 1777 BC: The Year Civilization Collapsed, pg. 107

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: A Trip Through Thucydides (Fear, Honor, and Interest),” A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, December 5, 2019, https://acoup.blog/2019/12/05/collections-a-trip-through-thucydides-fear-honor-and-interest/

For a good discussion of this, see Garry Adelman, The Myth of Little Round Top (Gettysburg: Thomas Publishing, 2003).

“History & Culture,“ Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site, August 29, 2022, https://www.nps.gov/sand/learn/historyculture/index.htm

Horwitz, “The Horrific Sand Creek Massacre.”

Horwitz, “The Horrific Sand Creek Massacre.”

Shanna Lewis, “Here are two new ways to learn about the Sand Creek Massacre in Eastern Colorado,” Colorado Public Radio, December 11, 2023, https://www.cpr.org/2023/12/11/eastern-colorado-sand-creek-massacre-online-on-site-learning-experience/. Barbara O’Neil, “History Colorado Center Unveils Sand Creek Massacre Exhibit,” 5280, November 21, 2022,

Goes without saying, but please don’t get your understanding of Tudor England from The Tudors.