On August 21, 1939, 85 years ago this month, five men walked into the Alexandria Library. Their plan was to use their presence as a protest against the segregated facility and strike a blow against Jim Crow segregation in their southern town. Samuel Tucker, a young Black lawyer, organized the protest, which sent him and his allies on a collision course with the powerful white establishment.

Recently, I had the privilege of sitting in the very library where the protest took place to interview Dr. Brenda-Mitchell Powell, the author of Public In Name Only: The 1939 Alexandria Library Sit-In Demonstration. This is the first part of our two-episode discussion about the sit-in and the city’s long road to integrating its library facilities. Listen to Part II here.

Listen to our conversation or read the transcript below.

If you’re in the Alexandria area next week, Dr. Mitchell-Powell will be discussing the legacy of the 1939 Sit-In protest on Wednesday, August 21, 2024, at 6:30 pm at the Alexandria Library. The event is currently sold out, but continue to check the events page to see if any spaces open up: https://alexlibraryva.org/event/11410770

You can purchase Dr. Mitchell Powell’s book on Amazon or directly from the publisher.

Friendly note: I’m still a bit of a novice at podcasting, so you might have to adjust your audio. Your patience is appreciated.

Transcript

Scott Vierick

Hello and welcome to another episode of the History's Confluences podcast. I'm your host, Scott Vierick. Now, if this is your first time listening, History's Confluences is an online publication featuring articles and podcast episodes about history, historic preservation, historic interpretation, museums, and historic sites.

Today's episode is a co-production with the Alexandria Historical Society. The Alexandria Historical Society works to research and share the history of Alexandria, Virginia by publishing independent research, hosting lectures and special events, giving grants, and honoring the best of public history in the Port City with its annual awards program. Both myself and my guest today sit on the board of this organization, which is turning 50 years old this year.

However, that's not the anniversary we're talking about today. No, today's discussion is about a landmark civil rights protest that happened 85 years ago this August; the Alexandria Library Sit-In Demonstration. On August 21, 1939, five African American men walked into the Alexandria Library. When the librarian at the desk refused to grant them library cards, the men grabbed books off the shelves, sat down, and started to read. Alexandria, a small city just to the south of Washington, D.C., was then under the regime of Jim Crow segregation. The Alexandria Library was restricted to white patrons only, and Black residents of Alexandria had to travel to Washington, D.C. if they wanted to use a library facility. By entering the library, these five men were challenging segregation and the power structures that sustained it.

Today, I'm sitting in the very library where the protest took place, and I'm joined by an expert on the topic, Brenda Mitchell Powell. She is the author of Public in Name Only, the 1939 Alexandria Library Sit-In Demonstration published by the University of Massachusetts Press. Dr. Mitchell Powell earned her PhD in archives management from Simmons University in 2015, where she was an American Library Association Spectrum Fellow.

She was a senior international correspondent for African Link, and was the editor-in-chief of Small Press Magazine. She also created, edited, and produced Multicultural Review, an international education and library resource. She has also served as a lecturer at Howard University. She is a member of the American Library Association, the Society of American Archivists, and Virginia Africana.

While working on her Ph.D., Dr. Mitchell-Powell accessioned and processed the Samuel Wilbert Tucker Collection at the Alexandria Black History Museum, which is an appropriate segue into our discussion. Samuel Tucker, after all, is a key part of the story of why, on that August day, those five men walked into the Alexandria Library and opened up a new chapter in the struggle for civil rights in the United States.

music

So, to start off, I'd like to discuss a little bit about Samuel Tucker, the man who planned the protest. Can you tell us a little bit about who he was and his path to organizing the sit-in?

3:50

Dr. Brenda Mitchell-Powell

Samuel Tucker was an activist even as a young person. At the age of 14, he, his younger brother Otto, and his older brother George were arrested on a streetcar because a white woman had charged them with abusive language.

4:18

Scott Vierick

And was this in Alexandria?

4:19

Dr. Brenda Mitchell-Powell

This was in Alexandria, yes. The boys had simply turned around the seats in front of them. All the seats were reversible seats. There were plenty of seats in the white section, so she certainly had ample opportunity to pick one of those chairs. The fact that she was upset about this one particular chair was a personal decision rather than a transit one. But anyway, the boys went to court. Otto, because he was so young, he was only 11, was dismissed. Samuel was charged $5 for the crime and court costs. And George, the oldest of the three boys, was charged $50 as a fine and court costs. Subsequently, a lawyer who was a friend of the Tucker family appealed the boys' conviction. And with an all-white, all-male jury, the boys were acquitted. So, it worked out well.

Samuel Tucker's mother had been a teacher before her marriage, and she and her husband, they were both activists and particularly involved in civil rights. They taught their children that initiating personal agency to accomplish a goal or to initiate a goal was one of the most important things you could ever do. She taught him to read before he went to kindergarten, and he continued on his life as a voracious reader and continued with his parents' tutelage of social activism. And got very involved in NAACP activities, activities by social activist Blacks in Alexandria. And it really set the path for a takeoff route for him to himself be a social activist for civil rights.

7:07

Scott Vierick

So, I guess my next question would be, why 1939, and why the library? Alexandria, at that time, you would have no shortage of targets to protest Jim Crow segregation, given that this was a segregated city in the South. Why did he hone in on the library, and what made him decide to do it in August of that year?

7:34

Dr. Brenda Mitchell-Powell

Tucker chose the library as a sit-in venue because he understood, from his own childhood growing up lacking the option for secondary education, that libraries were components of a community's educational superstructure…infrastructure.

Samuel Wilbert Tucker wanted to go to high school, as did his brother George, but there were no high schools for Blacks in Alexandria in 1933 when he was going to school. Samuel Wilbert Tucker's parents wanted him and all their children, they had four children, three boys and a girl, to go to high school. So, they essentially bootlegged an education for the children by letting them use the address of a friend of the family in Washington, D.C. as his home residence, so that he could enroll in the DC school system.

Samuel Tucker realized the importance of education for all citizens, certainly for Blacks as well as whites. Although at that time, throughout the South, and in communities beyond the South, Blacks were frequently denied opportunities for education because it was perceived as the province exclusively of whites. Blacks were not seen as having critical thinking skills, and so they felt there was no need to educate them, no need to provide them with schools beyond the eighth grade.

So, Samuel understood the value of self-education, which is the province for all. And he went on to pursue that self-education in order to teach himself the law, because he wanted to be a lawyer. He never went to law school. He practiced and was tutored by a gentleman who was a friend of his father's, a Mr. Watson. And Tucker did chores and conducted research at the Library of Congress even before he was 12 years old for Mr. Watson and realized what a benefit that had been to him. And he felt that everyone deserved it, those kinds of privileges, especially Blacks, because they were denied formal education by the community. So he saw libraries as integral to educating the entire person, not just the education limited by the demands of the curriculum authorities. And certainly for people who never got to go to school beyond the eighth grade.

The year was actually very important. In 1935, the African National Congress, which was a labor organization, a union, a labor organization for Black men, had their conference in Virginia, and they were protesting for union admission of Blacks into white unions, or at least social and civil justice, so that their union would be recognized. In 1936 to 1937, the union workers, who were automobile workers, conducted successful, what they called sit-down strikes. This was before the term sit-in had been coined. And he realized that sit-ins could be a productive, direct-action way to encourage change, if not desegregation or integration.

12:57

Scott Vierick

So, a sit-down strike is you're in the factory, and you're not working, but you are in the factory as opposed to picketing in front of it, correct?

13:05

Dr. Brenda Mitchell-Powell

Exactly, exactly, exactly. And although the sit-in demonstration was the first protest, overt protest, for Blacks against segregation directly, other demonstrations had been conducted, but they were always pickets or boycotts, and they were conducted for extension of service provisions, rather than erasure of segregation. So, this became a very important event in Tucker's life.

In 1937, also, the Alexandria City opened its first public library. Up to that point, the library had been a private facility. But they did not allow Blacks to use the library. It was actually in their bylaws that Blacks were to be excluded. Samuel was incensed by this. He lived just a couple of blocks away from the library.

And although they were not allowed to use the library, taxes were still imposed on Blacks to help subsidize the library for use exclusively by whites. And Samuel Tucker saw this as a real affront. He realized how unfair it was and wanted to do something about it. He decided to wage his own protest. And it became a two-pronged affair. The first part involved convincing a friend of his, a retired army sergeant and a Black Alexandrian, to attempt to get a library card at the Alexandria Library.

15:24

Scott Vierick

And what was this gentleman's name?

15:26

Dr. Brenda Mitchell-Powell

George Wilson was his name.

15:30

Scott Vierick

So that was the first part, was to have George Wilson go in...

15:34

Dr. Brenda Mitchell-Powell

And attempt to get a library card. Of course he was refused. And he and Samuel Tucker, because Tucker had gone with him, exited the premises. But Samuel, this made Samuel even angrier. So he decided to stage a sit-in protest as a continuation of his direct action for civil rights. And that became the Alexandria Library Sit-In Protest.

16:12

Scott Vierick

And so, when the protest happens, Samuel Tucker is not actually in the building. And we'll get into where he was and what he was doing. But ultimately, it was a group of five other men who went into the library. Can you talk a little bit about who they were and how they got involved?

16:30

Dr. Brenda Mitchell-Powell

Yes, they were actually all either friends of the Tucker family, or friends of the children of the Tuckers. And they knew each other very, very well. And, although he originally enlisted 11 participants, on the day of the sit-in, only six were left. The other five were not allowed to continue because their parents feared for their safety (Note: after recording, Dr. Mitchell-Powell asked that we clarify that one man missed the protest because he overslept). And this was perfectly understandable given the social environment in the community.

17:20

Scott Vierick

As context for our listeners, there are at least two lynchings in Alexandria's history. And of the two we have documentation for, both of them would have been within living memory of many in the city's Black community at the time of the sit-in demonstration.

17:38

Dr. Brenda Mitchell-Powell

Exactly. Exactly. They had actually occurred less than, less than 40 years prior to the sit-in demonstration. So this was a significant point. The five men were trained arduously by Tucker in his law office so that they would know precisely how to conduct themselves, what to wear, why not to speak if they were confronted by the librarians or the police. And how to act should the police attempt to remove them from the library. Those men were Otto Lee Tucker, younger brother of Samuel Tucker, Morris L. Murray, Edward Gaddis, Clarence Strange, and William Evans. Clarence Strange's younger brother, young Robert Strange, was not one of the protesters, he was only 14 years old, but he wanted to be part of the event. And so Tucker decided to make him a runner between the library and Tucker's office so that as events unfolded, he could run back to Tucker's office and relay the information as it happened, but he never physically entered the library. So there was no occasion and no reason for him to be arrested. So Samuel Tucker did not fear for his safety. He knew the other men would be arrested and intended to serve as their attorney.

19:52

Scott Vierick

And talk a little bit more about the preparations they went through. It seemed, to me at least reading your book, that Tucker was very concerned that the white press and the white authorities might try and spin it that, “oh, they were arrested for something else and not being in the library.”

So it seems like he was very much concerned that they wouldn't do anything that could be construed in such a way as taking away from the actual protests.

20:22

Dr. Brenda Mitchell-Powell

Exactly. Taking away from a nonviolent civil disobedience protest. And he... really stressed this point with the men because he knew the librarian, the library assistants, and the police were going to want to remove the men from the library. Their presence at the library was considered an affront by the white community who never thought Blacks would want library privileges, much less take it upon themselves to conduct a protest to achieve these goals.

21:10

Scott Vierick

And so, walk me through the events of the day of the protest. So, the five men walk in, they're dressed, correct me if I'm wrong, they're dressed in suits, they're dressed in their Sunday best, and they go in through those doors, and what happens next?

21:27

Dr. Brenda Mitchell-Powell

Well, they enter the library one at a time in five-minute intervals. Tucker has instructed them to go to the circulation desk and to ask for a library card application. Of course, upon requesting the application, they were refused, and it was expected by the library staff that they would then turn and leave the library. But no, Tucker had instructed them, subsequent to being refused an application, to go to the library shelves pick a book at random, and they were to pick books from different shelves, so that it could not be perceived that they were trying to create some sort of chaos in the library. Each man then took his book, sat down at a different table in the library so that they could not be accused of talking to one another, and then simply read. At that point, another protester would come into the library. And this went on until all five men were in the library seated and reading books.

22:56

Scott Vierick

And it's fascinating reading the accounts of what happened that day and just the simple act of going to the library, picking out a book and sitting down and reading quietly was causing chaos amongst the staff. And they're trying to figure out how to respond to it. And they call the police and the police are trying to figure out how to respond to it. Walk me through the freakout that is going on among the library staff.

23:25

Dr. Brenda Mitchell-Powell

The staff and the patrons, the white patrons who were in the library at the time of the protest, were very much taken aback by this arrogance on the part of Blacks thinking that they had the right to use the library; even though their taxes paid in part to subsidize the library. They had no clue as to how to respond. One of the library assistants actually went upstairs to the second floor of the building to get the librarian who immediately…she lived upstairs…She immediately rushed downstairs and made a point of going to the men and telling them they could not be in the library; they were not welcome in the library and that they had to leave. They still wouldn't go. Then she finally called the city manager and the police chief.

And the police chief sent two officers over to the library to arrest the men. One was named John Wilkerson, And the other one was John Kelly. John Kelly features more prominently in the story. Wilkerson seems to drop off the face of the earth after initially going into the library. There is no primary source evidence of him speaking to the men or trying to get them to leave. Nothing like that whatsoever.

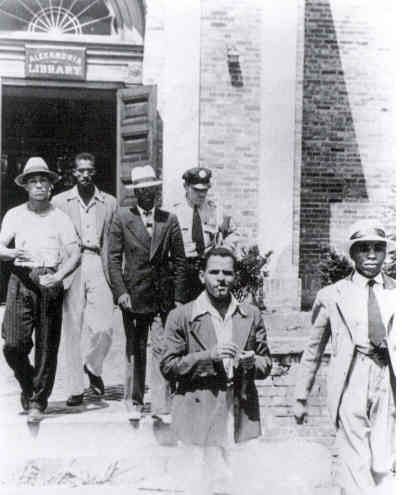

But finally, one of the protesters spoke up, and that protester was William Evan. William Evan spoke up and said, “Well, what would happen if we don't leave?” And this was against everything Tucker had tried to instill in the men. And it was a potential undermining of the entire protest. Buddy Evans then said, “Well, we're staying.” After that second comment, the protesters were removed from the library. They were quietly, no force was made, but quietly encouraged to leave the library premises. And there's an iconic photograph from the Washington Tribune, a Black paper in the city, of the five men being escorted from the library. They were immediately taken to the police jail.

26:34

Scott Vierick

I want to back up just a little bit. The fact that we have that photo, that wasn't a coincidence, that was all part of Samuel Tucker's plan. So, the doors to the library open, the men are being let out by the police and what greets them?

26:48

Dr. Brenda Mitchell-Powell

Samuel Tucker was very media savvy, incredibly media savvy. I mentioned previously that he had been a voracious reader and read all sorts of national newspapers. So, he decided in advance of the protest to contact the Black and white media to alert them to the fact that this civil rights protest was going to take place.

So, they all showed up and were there on the scene when the men were escorted from the library. At that point two, two to three hundred other visitors were at the library. And they too saw the men being escorted from the library. And this made front page news, even in the white papers.

It was a front-page story for the Alexandria Gazette, the city's paper of record.

27:58

Scott Vierick

So, what happens next after that? So they're led to the police station...

28:03

Dr. Brenda Mitchell-Powell

They're led to the police station. Interestingly, immediately after they're led to the police station, they have their arraignment. Usually, there's a period of time between arrest and any subsequent police action. But in this particular case, the arraignment immediately followed the men's appearance after the protest. Tucker then goes to the jail, pays the men's bonds. They're released on their own recognizance, which is surprising in and of itself. One would think that the men would be held in jail for causing such a disturbance in terms of normative standards in the city. But no, that did not happen.

On August 29th, they had their third hearing. And at that time, no decision was made about the outcome of the arrest. The men were simply left to be on their own recognizance and were simply told to appear in jail when they were told to do so. Samuel Tucker has made all of this clear to the men prior to the protests so they were not surprised and understood which steps would follow which preceding steps.

On September 1st, an initial hearing for the law case that Samuel Tucker had lodged against the librarian and the Alexandria Library for George Wilson's attempt to get a library card. Tucker filed what's called a writ of mandamus, which is an order from a superior official to a lower official, meaning instructions from the court to the librarian, that the men had to be admitted to the library and should be given library privileges. All of these things are happening in rapid action, and the two cases for a time are going on simultaneously.

Later in September, a first ruling was handed down by the court for the George Wilson case. And a continuance was issued as requested by the prosecuting attorney, Armistead Lloyd Booth. And he was also, interestingly, the vice president of the library board, and he sat on the city council as well.

31:39

Scott Vierick

And Booth is a really fascinating character who, when it comes to 20th century Alexandria history, he shows up a lot. And his overall civil rights record is, for lack of a better word, very interesting. Unfortunately, we don't really have time to talk about it now.

For our purposes, looking at the case, he's very much fighting back against Samuel Tucker. You write in the book, and I think this really summarizes his role so well, you write, "He personified tradition, continuity, and the status quo. As city attorney and vice president of the library board, he vigorously prosecuted the demonstrators and forcefully represented the interests of city and library officials. His exuberance led him to present questionable arguments rejecting the 14th and 15th Amendments.” So, he's quite the foe to Samuel Tucker.

So, we could do a whole episode just about the case, but in the interest of time, I'd like to ask you to talk about how the court case, for lack of a better word, ends. Because it's very interesting from a historical standpoint.

32:59

Dr. Brenda Mitchell-Powell

That's true. After the third hearing, there was no action taken by Judge James Reese Duncan. And he simply let the trial elapse. Things just dropped. Nothing happened. He did not get in touch with the men about subsequent actions.

The judge called Booth and Tucker into his chambers for private discussion after he made no ruling on the case. It is unknown what happened in the judge's chamber because the two attorneys, Tucker and Booth, were essentially sworn to secrecy by Duncan, so the case was not discussed by them. Tucker left the judge's chamber first and went out to meet a throng of visitors who wanted to know the outcome of the case. He could simply tell them that no decision had been made and that the men would continue to be free on their own recognizance. They served no jail time, and they were never fined for their participation in the protest. Booth left next. I found little evidence in the primary records about what happened with him. Like Tucker, he made no comments to the citizens interested in learning more about the final execution of the case, it just seemed to lapse. And Duncan not having made a ruling means that there were records that would have been in the court filings that were never there. They were never recorded because no decision had been made on the case.

35:34

Scott Vierick

We're gonna talk about how Tucker reacted to some of the decisions made by the library board moving forward. But through your research, did you get a sense of how he reacted to the judge's decision beyond what he told the crowd? Was there anything in his papers that contextualized how he reacted even if they didn't illuminate what was actually said in the space?

35:59

Dr. Brenda Mitchell-Powell

I understand what you're asking and wish I could answer your question intelligently. But unfortunately, I was unable to find any primary source records that record Samuel's Tucker's response to the judge's actions, he realized that there was little that he could do.

In the meantime, a group of accommodationist blacks approached the library board, and the librarian, and told them that it would be perfectly acceptable to them if a boy’s club were established instead of a library. So in doing so, they potentially undermined Tucker's case.

37:08

Scott Vierick

Do we have the names of who made up this group?

37:12

Dr. Brenda Mitchell-Powell

No, there's no record of who the accommodationists were.

37:17

Scott Vierick

Gotcha.

37:19

Dr. Brenda Mitchell-Powell

But there were Black citizens in Alexandria, as there were Black citizens all over the country, who wanted to stay away from involvement in what was perceived as a potentially dangerous scenario. They were content to accommodate white wishes, to be subordinate to the white establishment, and to bow to their decisions.

It's unfortunate because it meant that Tucker was battling not only the white establishment, not only a white court and judge and prosecutor, but city Black accommodationists as well.

38:16

Scott Vierick

So this group makes the offer about the boy’s club as the library board is having all these discussions and debates while the court case is ongoing. So, talk about what's going on with the library board and the ultimate decision they make.

38:33

Dr. Brenda Mitchell-Powell

Well, they knew for years that Blacks deserved to have library services, but they chose not to act on anything and deferred all decision-making to the city council. The city council deferred things as well. And so the issue continues to be dropped by the powers that be. It was simply kicking the can down the road, in effect.

And the next involvement is the court case of George Wilson on January of 1940, the 10th of January, precisely. Judge William Pape Woolls handed down the decision that had George Wilson attempted to fill out his own application (so evidently, Tucker was the one who was going to be filling out George Wilson's application on his behalf) and if Wilson had identified himself as an Alexandria resident, the library board would have been compelled to grant him a library card. But he did not do those two things, and so his request was denied. But because the library board and the city council and the white establishment realized that this essentially left the door open for Blacks applying for library cards, they hustled to make decisions as quickly as possible to erect a separate and unequal Black library in the city. This they did, and that became the Robert H. Robinson Library.

It's interesting because the library was named for the grandson of Martha Washington's personal maid. I found no evidence whatsoever that the Black community ever had any input into the library's naming. So again, they were cut out of the scenario. They were simply excluded from consideration as they had been throughout the trial and throughout the judgments.

41:39

Scott Vierick

A separate and unequal library. Not the outcome Samuel Tucker was hoping for.

Join us in our next episode as we discuss the Black community's reaction to the Robinson Library, Samuel Tucker's next steps, and the ultimate story of how the library system in Alexandria desegregated.

To make sure you don't miss the next episode, follow the Alexandria Historical Society on social media, or subscribe to History's Confluences.

Thank you to Brenda for sharing her expertise, the Alexandria Historical Society for co-producing this episode, and the Alexandria Library for hosting us. Until next time, this has been History's Confluences.