You’re reading History’s Confluences, which features historical research, trip reports, book reviews, and public history opinions and analyses.

Nestled in the Blue Ridge Mountains at the confluence of the Potomac and Shenandoah rivers is Harpers Ferry National Historical Park. Stretching across parts of West Virginia, Virginia, and Maryland, the park is full of history. Visitors from all over the world travel here to view exhibits, participate in ranger-led tours, and view living history demonstrations about John Brown’s Raid, the 1862 Battle of Harpers Ferry, the historic HBCU Storer College, and many other historical events and stories connected to the area’s past.

But while history is a powerful draw, it’s not the only reason people come to Harpers Ferry.

For many visitors, Harpers Ferry is known just as much for its natural beauty and recreational opportunities as it is for history. People on canoes, kayaks and whitewater rafts travel down the Shenandoah and Potomac rivers.1 Thru-hikers on the Appalachian Trail walk through the historic town on their journeys to Maine or Georgia, while day hikers head up one of the nearby ridges. Nature lovers aim their binoculars and cameras to the sky to look for local birds, like peregrine falcons. Bicyclists pass by on the C&O Canal.

But that doesn’t mean the hikers and animal watchers are avoiding any engagement with the past. Signs, exhibits, and videos, examples of what people in the public history world call “interpretive media,” complement the ranger tours and offer opportunities for self-directed, on-demand history exploration. Someone hiking on the Appalachian Trail may not have come to Harpers Ferry to learn about the past, but the waysides in the park offers a convenient excuse to take a short rest and drink some water. When the hiker sets off again, they’re a little more rested, a little more hydrated, and a little more informed about the area’s history. It’s something I observed multiple times when I worked as a ranger at the park.

Harpers Ferry has one of my favorite examples of effective interpretive media.2 On the trails heading up Maryland Heights a series of signs (also known as interpretive waysides) interpret the past. While many visitors head up the trails for exercise or to take in the views, strategically placed, well-written signage helps connect them to the heights’ military, economic, and political history.

Younger than the Mountains

Maryland Heights is one of several prominent ridges in Harpers Ferry National Historical Park. Located across the Potomac River from the historic Town of Harpers Ferry and standing at 1,400 feet, it’s hard to miss during a visit.3 Today, the forested slopes hide the mountain’s industrial history. The nineteenth century saw extensive logging on Maryland Heights by workers to feed the growing charcoal industry, and by soldiers and civilian workers during the Civil War.4 To paraphrase John Denver, on Maryland Heights, life is old there, older than the trees [because many of the old growth forests were chopped down].

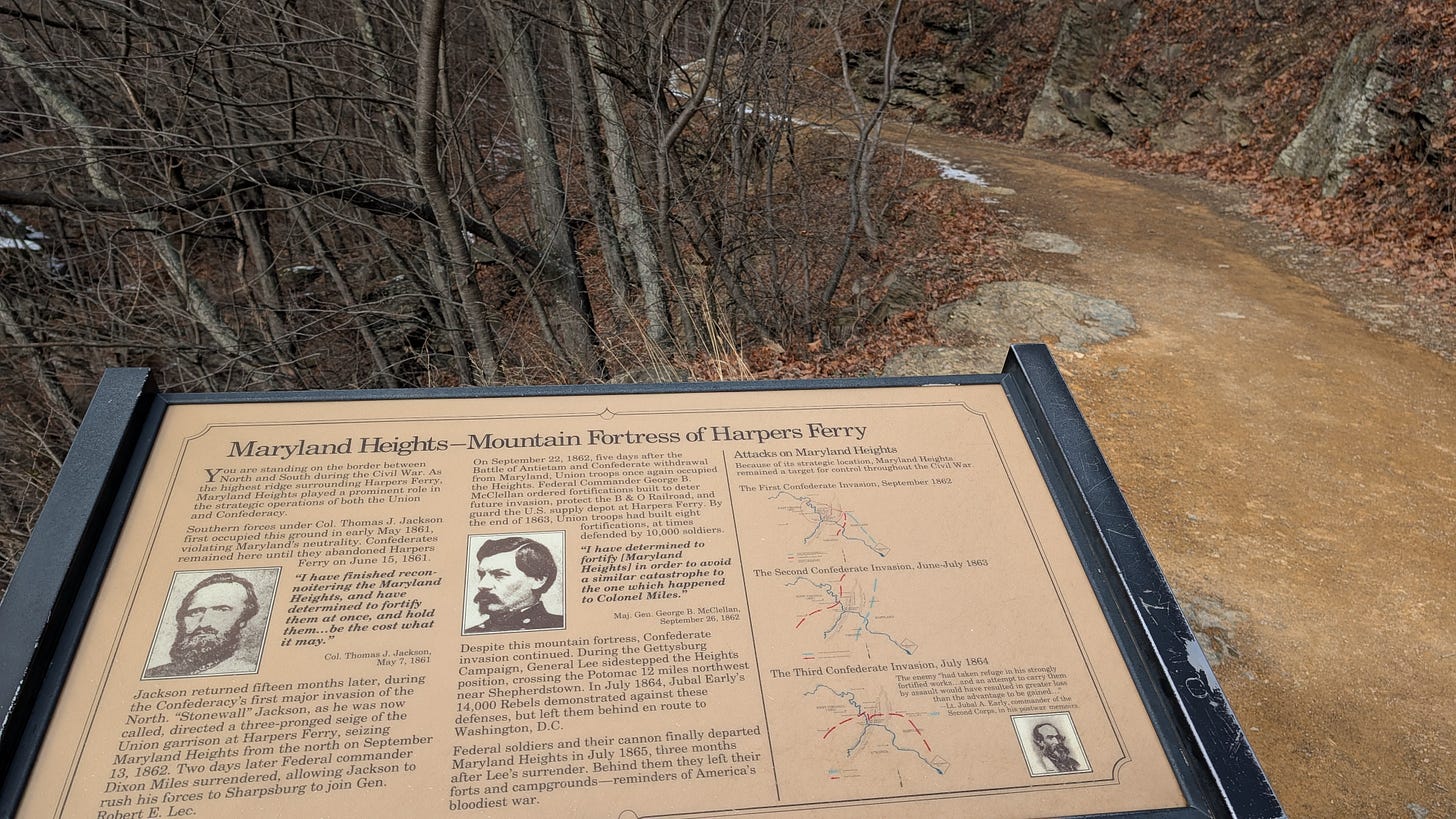

Given its commanding presence, it’s no surprise that Maryland Heights figures prominently in Harpers Ferry’s Civil War history. In September 1862, as General Stonewall Jackson’s Confederate soldiers began encircling the town, Union commander Colonel Dixon S. Miles knew he needed to hold Maryland Heights if his garrison was to survive a siege. Unfortunately for Miles, and despite a fierce defense by Union troops, Confederates under General Lafayette McLaws captured Maryland Heights on September 13. As his men retreated, a horrified Miles screamed, “They are coming down! Hell and Damnation!”5

The Union garrison continued to resist but eventually surrendered two days later on September 15. More details about this battle and the concurrent Battle of South Mountain can be found here.

The Confederate occupation of the captured town was brief, and when Union forces reoccupied the area, soldiers and civilians workers constructed an expansive series of fortifications on Maryland Heights. Future Union commanders would learn from the 1862 debacle. When sizable Confederate forces approached in 1863 and 1864, the Union garrison simply abandoned the town and retreated to the defenses on Maryland Heights. Heroic? Not really. Smart? Absolutely.

After the war, the fortifications on Maryland Heights were abandoned. Advertisers affixed a large ad for Mennen’s Borated Talcum Toilet Powder ( a skincare product) to the side of the mountain in 1906, which, despite several removal attempts over the years, remains visible today.6

When the federal government began purchasing land for Harpers Ferry National Monument (later Harpers Ferry National Historical Park), various property owners held title to the land on Maryland Heights, and trying to figure out who owned what proved to be a challenge.7 Eventually, however, those issues were resolved, and in 1963 NPS officials were able to purchase much of Maryland Heights and add it to the park.8 They acquired an additional parcel of land on the mountain in 1992.9 Today, Maryland Heights is a key part of Harpers Ferry National Historical Park, and a favorite hiking spot for both locals and out of town visitors.

A hike up Maryland Heights

Hikers who wish to travel up to Maryland Heights start their journey by leaving the town of Harpers Ferry and using the footbridge on the CSX railroad bridge to cross over the Potomac River. After a short walk along a section of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal Path, they cross Harpers Ferry Road and begin their ascent. A wayside a short way up the hill provides an overview of the mountain’s Civil War history. From a point where a hiker can still see the both the town of Harpers Ferry and the Potomac River, the sign reminds the hiker that this was a borderland area during the war, with divided loyalties, political uncertainty, and the ongoing threat of violence.

Each wayside on the trail can be enjoyed independently, so hikers aren’t penalized for skipping one. This is helpful not only for hikers who don’t necessarily want to stop at every single sign, but also because there are several side trails and branching paths on Maryland Heights that make a comprehensive hike a little challenging.

As visitors make their way further up the trail, a short loop allows them to walk around the former site of the Naval Battery, where a set of large guns from the US Navy Yard in Washington DC once stood. A wayside tells the battery’s history as one of the first defenses built on Maryland Heights by the Union Army and the failed efforts by its garrison to halt the Confederate advance during Battle of Harpers Ferry.

Eventually, hikers come to a fork in the road and another sign.

This interpretive marker is doing double duty. Not only is it connecting visitors to the history of the path they’re on, but it’s also providing them with logistical information about their hiking options.

For some hikers, this is the end of the road. Seeing the additional distances (and the steep incline on the trail on the left) prompts them to turn around. That’s why the sign’s interpretive content is important. It clearly states the history and its connection to the resource (visitors are using the same road that Federal troops did while retreating during the 1862 Siege of Harpers Ferry) with a short, concise piece of text and an accompanying image that evokes the historical scenes.

Two paths diverge from this sign. Visitors who head to the right make their way to a rocky overlook. Even if you’ve never done the hike, you’ve probably seen the iconic view it offers of Harpers Ferry.

Visitors who head to the left are making a longer, significantly more uphill journey to the historic Stone Fort. As they climb, additional waysides discuss the history and provide a convenient place to rest and hydrate. Visitors who decide to make this hike encounter one of my favorite waysides, which features Abraham Lincoln’s aborted attempt to hike Maryland Heights.

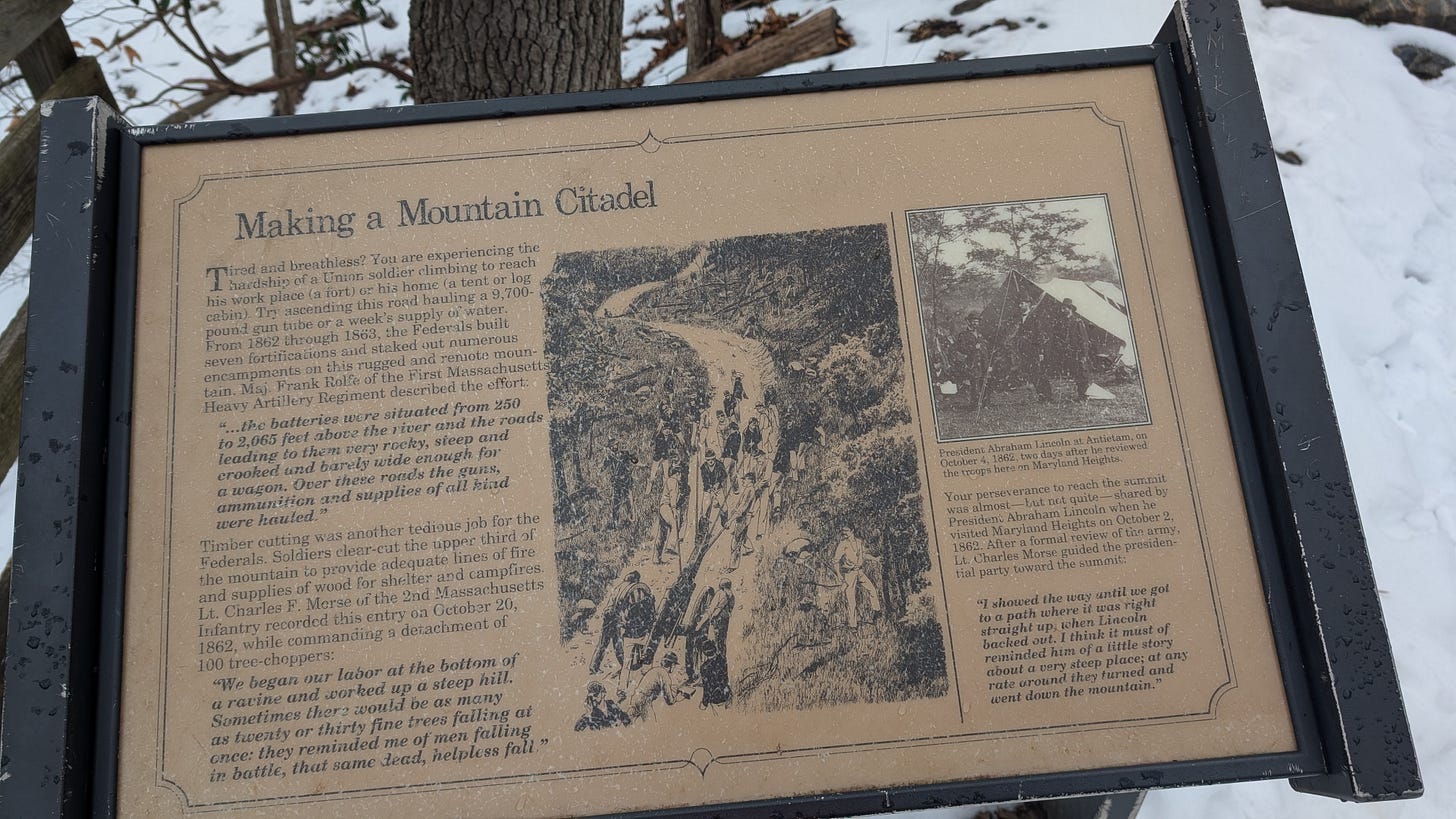

At it’s best, historical interpretation makes connections between the past to visitors’ lives and experiences. This is often easier said than done, but sign creators saw their opportunity to connect modern-day hikers experiences of trying to climb Maryland Heights with the experiences of Civil War soldiers trying to make their way up the Mountain. The text and the images here work together beautifully. “Try ascending this road hauling a “9,700-pound gun tube or a week’s supply of water,” the panel reads, accompanied by an sketch depicting soldiers attempting to make their way up the trail while pulling a very heavy cannon. The text connects the emotions that many visitors are feeling as they make their way up the steep incline (tired, sore, frustrated) and asks them to consider the soldiers who had to make that same trek multiple times a week while sometimes hauling heavy equipment.

The panel also discusses a humorous story about President Abraham Lincoln’s visit in 1862. After reviewing the troops, Lincoln began to make his way towards the top of Maryland Heights. However, after seeing the steep incline he decided that, nah, climbing this mountain wasn’t for him and turned around. Maryland Heights, it seemed, caused the famously resolute president to give up. It’s a fun story that shows the human side of the often-mythologized 16th president, and it provides a subtle encouragement for the hiker. “Keep going,” it seems to read, “you’re doing something that not even Abe Lincoln could do.”10

The next wayside’s content is a little different than the others. Most of the interpretive signage on Maryland Heights discusses the Civil War, but this one breaks the mold by covering the history of charcoal making on the mountain. Historical interpretation isn’t meant to provide every single fact about a place. Doing so is impossible, and trying to include too many topics or time periods can adversely impact the learning experience and harm visitor engagement. So choices need to be made about what time periods to focus on and what stories to include. Ideally, a site will have an interpretive plan that helps staff focus their efforts. In this case, I think the charcoal wayside is appropriate. The sign is placed near the remains of a former charcoal hearth, anticipating the visitor’s question of “what’s that?” The content is connected to both the Civil War (the roads created by charcoal industry laborers were later utilized and improved during the conflict) and the modern-day hiker’s experience (the trail is on a former charcoal transport road). The sign is thematically linked to the other waysides on Maryland Heights even if the focus is on a different time period.

After departing the charcoal sign, the uphill trek continues. Eventually, the path levels out as the visitor approaches the remains of the Stone Fort. Built in the aftermath of the Union Army’s defeat and the surrender of the Harpers Ferry garrison in 1862, the fort was meant to serve as citadel to help prevent a similar disaster. The trail takes visitors through the remains of the structure, with waysides describing the various defenses and the lives of the soldiers who garrisoned it. Visiting on a winter day with the fort covered in snow, the sign describing the soldier’s housing and the poor weather conditions they faced really hit home.

The tree cover means that any visitor expecting 360-degree views from the top is going to be disappointed. But what the Stone Fort lacks in clear views it makes up for in solitude. The effort required to reach the fort means that its typically pretty quiet up there, and, at certain times, a hiker may find themselves alone with the mountain’s history. There are also a few vistas that offer the chance to take in the surrounding area.

From the Stone Fort, visitors can continue on the trail that takes them back down the mountain, passing by a few other gun batteries. However, many chose head back the way they came since that route is a little shorter.

Happy trails

Whenever I get a chance to go to Harpers Ferry, I try to make my way up to the Stone Fort. Are there things that I’d change? Sure. I’d like to see refreshed signs with tightened text, new graphics (Gettysburg National Military Park recently installed waysides with some striking illustrations), and updated scholarship. Research on the civilian employees who worked for the army on Maryland Heights, including freedmen who had escaped slavery, would enhance the stories told on the waysides. Likewise, information on the area’s Indigenous history could be added without diluting the trail’s interpretive focus. The sign focusing on antebellum charcoal workers could include a bit more information about their backgrounds, where they came from, where they lived when not working on the heights, and how many were paid workers and how many were enslaved.

Still, these current signs get the job done, and given that most visitors to the park don’t go up to the Stone Fort and many don’t even take walk on Maryland Heights at all I can understand if updating the signs isn’t a priority right now. The park, like many other National Park Service units, has many other pressing financial challenges to address.

The interpretive signage on Maryland Heights does what good interpretation should do, meaningfully connect visitors to the resource. As a hiker makes their way up the trail, the signage allows them to learn and empathize with the people who had to go up and down the mountain during wartime, sometimes under fire. The signs help make the past come alive, reinforcing to the visitor why Harpers Ferry National Historical Park is important not just from a recreational standpoint, but from a historic one.

Could the stories that are told on the Maryland Heights Trail be told elsewhere in the park? Yes, and many of them are.11 However, there’s a value to having them on the resource itself, where the visitors can stand where the soldiers and laborers once stood, lived, worked, and fought. Without the signs on the trail, many visitors would probably see Maryland Heights as just another place to go hiking. Having the waysides on the heights literally meets visitors where they are, creating a smooth connection between the information and resources interpreted. Likewise, the signage doesn’t try to tell stories that could be better told elsewhere in the park. The interpretive media is focused on the resource and the visitor, which makes for an engaging experience.

Make time for a hike

Hiking Maryland Heights can be challenging, but for the people who do, the history, the views, and the experience make it all worth it. If you’re able to hike the trail, I recommend it (but please be realistic about your level of physical fitness). Take your time going up, stop to read the waysides, pack food and water, and you’ll have a good time while engaging with its history. Plus, when you finish your hike and walk back across the bridge over the Potomac River there are plenty of great restaurants in town to grab a bite and toast your achievement. The feeling of looking at the the mountain you just hiked as you enjoy a cold drink and a good meal? Almost heaven…

All views expressed in this article are my own and do not represent the views of any of my employers, present or past

Note, while you can pass by the park while traveling on the river, you cannot launch a watercraft from within the park itself. Please follow all rules and regulations

Although I used to work for the park, I had nothing to do with the creation of the signs.

Earl J. Hess, “The Terrain and Fortifications of Harpers Ferry: September 12-15, 1862,” American Battlefield Trust, last accessed on January 27, 2025, https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/terrain-and-fortifications-harpers-ferry (And yes, I’m sure some of my readers out West would quibble with me calling Maryland Heights a “mountain”).

Hess, “The Terrain and Fortifications of Harpers Ferry.”

Dennis Frye, Harpers Ferry Under Fire: A Border Town in the American Civil War, (Virginia Beach: Donning Company Publishers, 2012, 83.

“Mennen’s Toilet Powder Sign,” National Park Service, last updated February 6, 2023, https://www.nps.gov/places/000/mennens-toilet-powder-sign.htm

Teresa S. Moyer, Kim E. Wallace, Paul A. Shackel, “To Preserve the Evidences of a Noble Past” An Administrative History of Harpers Ferry National Historical Park, (Harpers Ferry: National Park Service, 2004), pg. 159

Moyer, Wallace, Shackel, “To Preserve the Evidences of a Noble Past,” pg. 362.

Moyer, Wallace, Shackel, “To Preserve the Evidences of a Noble Past,” pg. 362.

An alternate reading is that its saying “Lincoln said ‘I quit,” and so you can too if you want.” Ultimately, the visitor can take whatever lesson they wish, but I think most who read it will probably soldier on.

Photos of the waysides and transcripts of the their text are also available online for visitors who may be unable to make the hike up Maryland Heights.