In September 1862, the Civil War was in its second year and the Confederacy’s fortunes were flying high. General Robert E. Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia had thwarted the Army of the Potomac’s advance against Richmond and then humiliated the Army of Virginia at the Second Battle of Bull Run. Meanwhile, other Confederate forces were poised to invade Kentucky, and the electoral prospects for President Abraham Lincoln and his Republican Party in the upcoming midterm elections looked grim. Still, Robert E. Lee knew that the picture wasn’t completely rosy for the South. The United State’s blockade of the Confederacy’s coast was growing, and Union armies in the west had notched several important victories. To end the conflict, Lee knew he’d need to secure European recognition of the Confederacy and convince the Northern public that the war wasn’t worth fighting. So, he decided to invade Maryland. Invading the Old Line State would allow the Army of Northern Virginia to resupply itself and give Virginia farmers a reprieve from growing crops in a warzone. A Confederate victory in Maryland, or nearby Pennsylvania, would also be devastating to Northern morale and could potentially prompt the European powers to recognize the Confederacy.

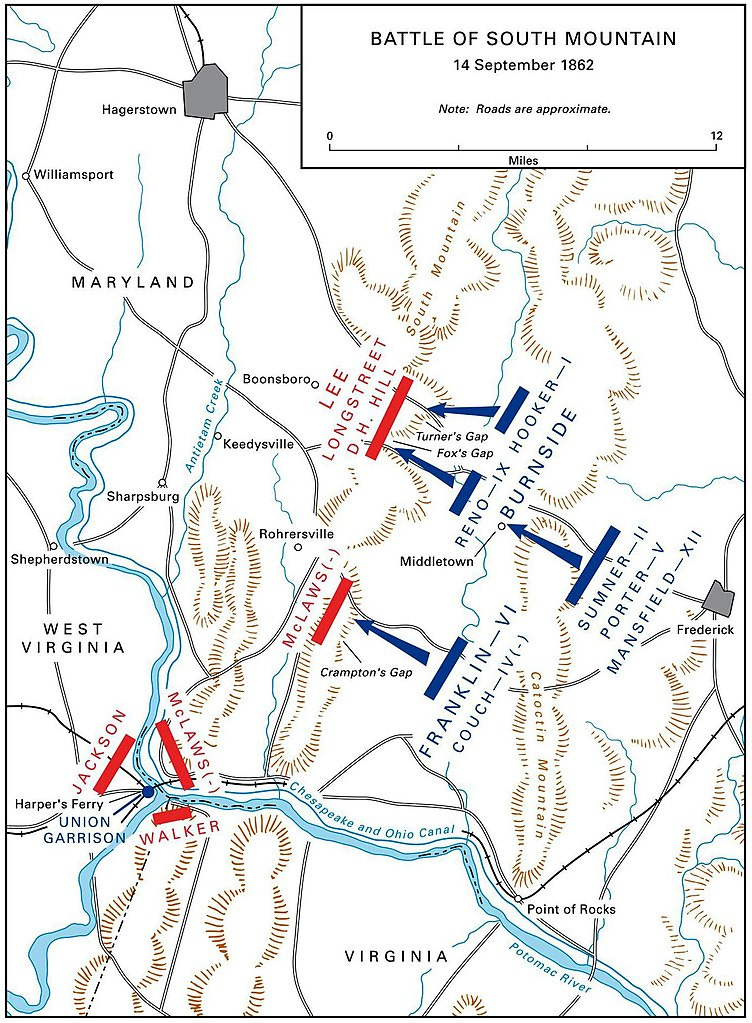

After crossing the Potomac River, Lee divided his forces. General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson was dispatched to capture the Union garrison at Harpers Ferry, Virginia (today part of West Virginia), while the rest of the army remained in Maryland. However, someone misplaced a copy of Lee’s orders, which were recovered by soldiers from the 27th Indiana regiment. General George B. McClellan, commander of the Army of the Potomac, now had an exact picture of Lee’s plans and how divided his troops were. With uncharacteristic speed, McClellan ordered his army in pursuit, but an obstacle blocked their path. South Mountain, a 70-mile ridge, separated the two armies, and Lee was rushing troops into the passes to block the Union advance. If the Army of the Potomac was going to destroy the Army of Northern Virginia, it would have to fight its way across South Mountain.

A century and a half later, I hiked through the same passes that the Union and Confederate forces had fought over. The path I followed was well-trod, and, if I wished, I could have continued hiking all the way to either Georgia or Maine. Such is the magic of the Appalachian Trail.

Starting at the Washington Monument… No, Not That One

Over the years, I’ve heard anecdotal stories of visitors at large battlefields with lots of monuments asking questions like “How did they fight around those monuments?” or “Why were so many battles fought at National Parks?”1

I’ve never gotten firm confirmation that these stories are true, but I bring this up because my hike started at the site of a monument that DID play a role during the Civil War. As the two sides clashed, Confederate artillery officer Edward Porter Alexander described seeing “some sort of tower on the mountaintop.” Roughly 30 years earlier, residents of Boonsboro, Maryland, had erected a structure on South Mountain as a monument to George Washington. When the Civil War broke out, the structure was used at various times as an observation platform by U.S. forces. During the Battle of South Mountain, local residents climbed to the top of it to try and see the action.

Today, the monument is managed by the Maryland Park Service and boasts a small museum and picnic shelter (humorously named “Mount Vernon”). Visitors heading towards the monument are treated to a series of signs marking major events in George Washington’s life (southbound Appalachian Trail hikers encounter the signs in reverse order, so they get the Benjamin Button version of Washington’s story). The visitor center, while small, does a good job of discussing the monument’s creation, its role during the Civil War, and the efforts of the Civilian Conservation Corps to restore the monument during the 1930s after years of neglect. The view from the top of the monument remains spectacular.

The Washington Monument was where I started my hike. From there, the plan was to follow the Appalachian Trail (AT) 20 miles south to Harpers Ferry, passing through the gaps and passes that Union and Confederate troops battled over in 1862. This was a one-day hike but because it was also a practice run and equipment check for a longer multi-day hike in New York in August, I was carrying full pack of camping equipment.

Hallo Sam, I’m Dead

The Appalachian Trail is nicknamed “the Green Tunnel” for the amount of tree cover it offers and that was on full display during my hike. Aside from road crossings and a few overlooks, my time on South Mountain was very much a walk in the woods. This worked out in my favor. Even though it was the middle of summer, thanks to the tree cover, I was cool and comfortable. From the Washington Monument, it was a fairly easy walk to Turner’s Gap, one of several passes where Union and Confederate forces dueled for control. The Battle of South Mountain is best understood as a series of separate but related clashes for control of the strategic mountain passes on September 14, 1862. In addition to Turner’s Gap, the trail would take me through Fox’s Gap and Crampton’s Gap, both of which were scenes of heavy fighting.

At Turner’s Gap, the trail passed by the Old South Mountain Inn, which dates back to around 1732. According to the Boonsboro Historical Society, the inn served as Confederate General D.H. Hill’s headquarters during the battle.2 Forces under Hill’s command protected both Turner’s Gap and Fox’s Gap to the south.3 Facing east to where the fighting occurred, the trees made it hard to see the landscape, but it was clear the challenges facing both General Hill and his counterpart in the Union Army, General Joseph Hooker. Hill had the high ground but was vastly outnumbered. Hooker’s command was much larger than Hill’s, but he had to attack uphill. Ultimately, the Union forced the Confederates to give ground but were unable to fully drive them from their positions by the time night fell.

About a mile away from Turner’s Gap was Fox's Gap. As I approached Reno Monument Road, the trees on the left thinned out, and I could see a large open area known as Wise’s Field, which was the scene of heavy fighting during the battle. A sign informed me that the area had been preserved by the Central Maryland Heritage League. According to their website, they work to preserve and interpret the South Mountain Battlefield and hold several historic easements on land significant to Maryland’s history.4 The field itself only had one marker, but the American Battlefield Trust has a 360 virtual tour with hotspots interpreting the fighting and the soldiers involved, which you can view here (no hiking required).

Reaching the road, there were a few more waysides describing the action. At Fox’s Gap, Union forces under General Jesse L. Reno clashed with Confederate troops. The fighting took most of the day, but by early evening, the Union troops had pushed their foes back. Today, there’s a small monument to Confederate General Samuel Garland and a monument to the North Carolina troops who fought there, which is located along a side trail. Most prominent is the monument to General Reno, who paid for the victory at Fox’s Gap with his life. After being mortally wounded near the end of the battle, soldiers brought the general to the headquarters of General Samuel D. Sturgis, where the dying Reno greeted his fellow officer with “Hallo, Sam, I’m dead!” before passing on.5

A little way beyond Fox’s Gap, I encountered the steepest section of the hike, which featured a climb of around 600 feet over the course of slightly less than two miles.6 This was nothing compared with some of the other parts of the AT (or even some of the other parts of the Maryland section), and the view from the top was more than worth it.

Before long, I was coming up on Crampton’s Gap, where, like Fox’s and Turner’s Gaps before it, outnumbered Confederate forces attempted to hold back the Union soldiers. Union General William Franklin was under strict orders to push the Confederates out of the pass and then relieve the concurrently occurring siege of Harpers Ferry to the south (more on that later). Confederate forces guarding the pass numbered slightly over 1000 men, so Franklin should have been able to make easy work of them.7 However, Franklin delayed making the attack. This allowed Confederate reinforcements to reach the area. While Franklin’s troops ultimately took the gap, his delay would have serious consequences for his comrades to the south of the Potomac River.

Some of the battlefield here is preserved as part of Gathland State Park. Unlike some of the other parts of the hike, this one includes a very hard-to-miss feature.

The War Correspondents Memorial pays tribute to the journalists who chronicled the American Civil War as it happened, providing updates to readers on the home front. The text on the structure reads: “To the Army Correspondents and Artists 1861-1865/ Whose toils cheered the fireside/ Educated provinces of rustics into/ a bright nation of readers / and gave incentive to narrate / distant wars and explore dark lands.”8 The monument was a brainchild of George Alfred Townsend, who served as a reporter during the war and owned the land where the monument stands. Townsend called his South Mountain estate “Gathland” after his pen name “Gath.” The monument is a fascinating one and Chris Mackowski of Emerging Civil War has a nice write-up about it, which you can read here.

Gathland marked the approximate halfway point of my hike. From there, it was a gentle uphill back into the forest and then a few roughly flat miles before a gradual (but somewhat rocky) descent from Weverton Cliffs. There weren’t any waysides or interpretive materials along this stretch of the trail, as by this point, I’d passed the areas of active fighting. The Battle of South Mountain had more or less concluded by the evening of September 14, 1862. Union forces had been victorious, but Confederate resistance had bought Lee and Jackson enough time to reunite their troops near the banks of Antietam Creek.

After passing Weverton Cliffs, I descended South Mountain, crossed under Route 340, and then passed over some railroad tracks before reaching the point where the AT briefly joins up with C&O Canal National Historical Park. By now, I was ready for my hike to be done. I’d been hiking since 10 am, my water was gone, and I’d walked and biked this section of the C&O so many times that there was really nothing new to discover. Still, the trail was pancake flat which meant that traversing it didn’t take long. Before I knew it, I was crossing the Potomac River to my final destination, Harpers Ferry.

Hell and Damnation

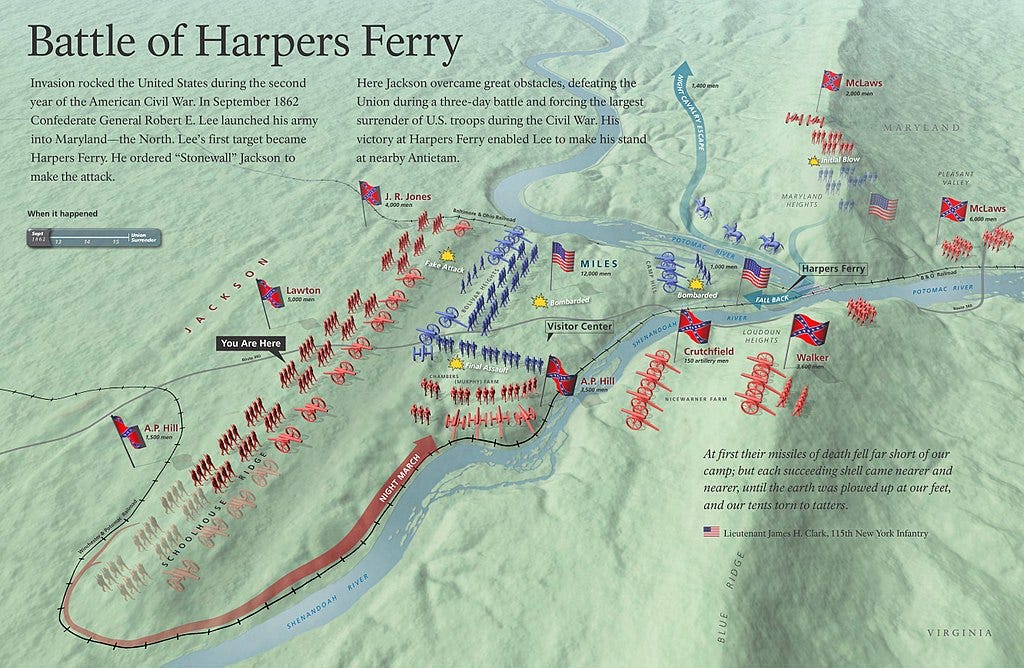

While the Confederate and United States forces battled in South Mountain, a separate but related battle was being fought in Harpers Ferry. Lee’s plan for the invasion assumed that the Union garrisons at Martinsburg and Harpers Ferry would evacuate. He was half right. The garrison at Martinsburg did evacuate…to Harpers Ferry, meaning that Lee had an enemy force of over 12,000 to his army’s rear. To deal with the issue, he dispatched Jackson to force the town’s surrender.

Meanwhile, in Harpers Ferry, Colonel Dixon Stanley Miles, the commander of the United States garrison, had his work cut out for him. In comparison to Jackson’s battle-hardened veterans, most of Miles’s command had only been in the army for a couple of months, while others had only been under arms for a couple of weeks. Geography was another issue. The strategically important town is surrounded by several high ridges, Maryland Heights, Loudon Heights, and Bolivar Heights. If the Confederates could gain control of any of these ridges, they could bombard the town. Meanwhile, the Shenandoah River separated the Union forces in Harpers Ferry from Loudon Heights, and the Potomac River separated them from Maryland Heights. Miles didn’t have enough troops to garrison each of the heights. To get around this, he decided to send troops up to Maryland Heights and Bolivar Heights. The former offered the highest position in the area, which meant that, in theory, Union canons could prevent Confederates from moving artillery to Loudon Heights. Meanwhile, Bolivar Heights blocked the land approach. If all went well, Miles could hold off Jackson long enough for reinforcements to arrive.

Unfortunately for Miles and the rest of the Harpers Ferry garrison, things quickly went south. Despite a fierce defense by Union troops, Confederates under General Lafayette McLaws were able to capture Maryland Heights on September 13. As his men retreated from the highest point on the battlefield, a frustrated and horrified Miles screamed, “They are coming down! Hell and Damnation!”9 By the afternoon of September 14, as Union and Confederate forces battled for South Mountain ten miles away, Confederate artillery on both Maryland Heights and Loudon Heights were bombarding Harpers Ferry. “There was no corner of safety for unnamed men, women, and children. They could do nothing but look up to the frowning mountain walls and await the storm of fire,” wrote eyewitness Mary Clemmer Ames.10 Still, the Union line on Bolivar Heights held firm, a serious problem for Jackson. Time was of the essence, and for every moment he spent besieging Harpers Ferry, the Union forces in Maryland got closer to completely overwhelming the rest of the Army of Northern Virginia.

With the bombardment taking too long, on the night of September 14th, Jackson ordered a flanking maneuver around the Union position on Bolivar Heights. The Confederates snuck around their US opponents and placed cannons near the Murphy-Chambers Farm and also across the Shenandoah near the base of Loudon Heights. From these spots, they could effectively target the troops on Bolivar Heights. As the Confederate cannons opened fire on September 15, it was clear that the battle was over. The Union garrison was trapped “like rats in a cage,” as one soldier described it.11 Miles gave the order to capitulate right before a stray shell, perhaps one of the last to be fired in the battle, mortally wounded him. The surrender of around 12,700 soldiers was the largest surrender of United States forces until World War II.12

The Confederate occupation of Harpers Ferry was brief. Jackson knew he needed to rejoin Lee, and quickly paroled the garrison (meaning that they weren’t going to a Confederate POW camp, but also that they were not allowed to fight again until a formal prisoner exchange occurred). However, the need to quickly rejoin the rest of the Army of Northern Virginia didn’t stop the Confederates from going through the town and kidnapping any African American civilians they found, whether born free or born enslaved, and dragging them into slavery. Hospital Matron Abba Goddard sadly noted, “Every nook, corner, cranny, barn, and stye has been searched, and men, women, and little children in droves have been carried off.”13 Historians estimate that up to 2,000 people may have been forcibly enslaved by the Confederates in the aftermath of their capture of Harpers Ferry.14

On the Bloody Banks of Antietam Creek

While the fighting at the Battle of South Mountain was fierce and the Union defeat at Harpers Ferry was humiliating, both battles would be overshadowed by another battle fought a few days later near the town of Sharpsburg. On September 17, 1862, the Army of the Potomac and the Army of Northern Virginia met in the bloodiest single day of the war. By the time the sun set, 23,000 soldiers were wounded, dying, or dead.15 Jackson’s men arrived in enough time to prevent the destruction of Lee’s army, but the high casualties eventually forced a reluctant Lee to retreat back to Virginia. While the Battle of Antietam itself was inconclusive, it was a strategic win for the United States. The Army of the Potomac had held firm and pushed the enemy out of a loyal state. It gave President Lincoln the victory he needed to issue the Emancipation Proclamation. My route didn’t take me near Antietam, but I was able to catch a small glimpse of it at the beginning of the hike

A Long Hike

The Maryland section of the Appalachian Trail is considered to be one of the easier sections, but I’d recommend that anyone interested in tackling this hike do their research and be honest about their physical fitness before attempting. The hike is over 20 miles long, and I was pretty tired by the end of it. Granted, I also had a heavy pack on me (this was a prep hike for a longer AT hike), but it’s not exactly a walk in the park even without the backpack. It took me about seven hours to do the whole hike and I didn’t have a lot of time to take in and read the waysides. That was fine for me, I’d done this hike before and visited most of these locations on other trips, but that approach might not work for everyone.

From a recreational hiker’s perspective, South Mountain is a great place to explore the outdoors. The trails are well-maintained, there are plenty of locations for parking, and the occasional wayside and monument make for an interesting diversion. That said, anyone who wants to really experience the Battle of South Mountain might want to instead plan a driving trip from one of the historic structures below the mountain and then drive up to the various gaps. This will allow you to follow the avenue of approach taken by the US soldiers and get a better sense of the topography of the battle. You’ll also be able to view parts of the battlefield that aren’t accessible from the AT. I’d also recommend picking up a book to help give you a sense of how the battle developed. I’d recommend John David Hoptak’s The Battle of South Mountain or Robert Orrison’s and Kevin Pawlak’s To Hazard All: A Guide to the Maryland Campaign, 1862.

Likewise, anyone who wants to combine South Mountain, Harpers Ferry, and Antietam into a single trip would be advised to drive. Most of the Battle of Harpers Ferry took place on the heights around town, and while the Maryland Heights, Loudon Heights, and Bolivar Heights/Schoolhouse Ridge trails are enjoyable hikes on their own, I wouldn’t recommend hiking South Mountain and then attempting to hike the Harpers Ferry Battlefield on the same day. Antietam is even more of a challenge. You’d need to hike up the C&O for a few more miles and then hike uphill along roads before you reach the battlefield. Can you do a multi-day hike and experience all of these places? Yes, but that itinerary won’t be most visitors’ cups of tea.16

Younger Than the Mountains

So what does the future hold for South Mountain Battlefield? Quite a lot, if the last few years are any indication. In 2019, Preservation Maryland commissioned an in-depth study and public consensus plan to discuss past preservation efforts and pathways for the future. The report recommended more interpretation at the battlefield, better branding, and additional preservation and archeology work.17 Preservation Maryland commissioned an archeological study of Crampton and Fox’s Gap and worked to stabilize Shafer Farm, which served as the headquarters for one of the Union commanders. Preservation Maryland and its partners are also in the process of a new re-branding effort which will hopefully clue in more visitors about the battlefield and encourage them to explore other sites relating to its story.18

As for myself, I’m looking forward to seeing more interpretation of the battlefield in the future. As a recreational trail, and particularly as part of the Appalachian Trail, the hike along South Mountain is great. From an interpretive standpoint, I’d like to see some side trails that take visitors along the route used by Union troops to attack each of the passes. This would give visitors a better sense of the terrain, the avenue of approaches used during the battle, and provide a more experiential hike. I’d also like to see more information about the civilians and communities who experienced the Maryland campaign as well. The Battle of South Mountain may be a part of history, but the battlefield’s future is still being written and I’m excited to see the next chapter.

Junior ranger badges. It’s the junior rangers badges that cause all wars.

“Old South Mountain Inn” Boonsboro Historical Society, https://boonsborohistoricalsociety.org/south-mountain-inn/

John David Hoptak, The Battle of South Mountain, (Charleston: The History Press, 2011), pg. 104.

“About Us,” Central Maryland Heritage League, https://cmhl.org/about-us

“Jesse L. Reno” National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/people/jesse-l-reno.htm#:~:text=Sturgis.,D.H.

David “AWOL” Miller and AntiGravityGear, The AT Guide: 2023 Edition,” (Wilmington: AntiGravityGear LLC, 2023), 114.

Hoptak, The Battle of South Mountain, 139.

Chris Mackowski, “Battlefield Markers & Monuments: The Civil War Correspondents Memorial,” Emerging Civil War, November 10, 2017, https://emergingcivilwar.com/2017/11/10/battlefield-markers-monuments-the-civil-war-correspondents-memorial/

Dennis Frye, Harpers Ferry Under Fire: A Border Town in the American Civil War, (Virginia Beach: Donning Company Publishers, 2012, 83.

Frye, Harpers Ferry Under Fire, 87.

Frye, Harpers Ferry Under Fire, 94.

“Harpers Ferry,” American Battlefield Trust, https://www.battlefields.org/learn/civil-war/battles/harpers-ferry#:~:text=At%20the%20time%20of%20the,in%20the%20Philippines%20in%201942. “1862 Battle of Harpers Ferry,” National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/hafe/learn/historyculture/1862-battle-of-harpers-ferry.htm

Frye, Harpers Ferry Under Fire, 102.

Frye, Harpers Ferry Under Fire, 102.

Robert Orrison and Kevin Pawlak, To Hazard All: A Guide to the Maryland Campaign, 1862, (El Dorado Hills: Savas Beatie LLC, 2018), 131.

Goes without saying, I’m not responsible if you try any of these hikes and have a miserable time. Hike at your own risk.

Mary Ruffin Hanbury and David W. Lewes, Public Consensus Building Plan for the South Mountain Battlefield, Baltimore: Preservation Maryland, 2019, pg. 41-44.

Branon Weigel, “New Branded Signage Linking Battle Sites to be Installed Near South Mountain,” CBS News Baltimore, September 13, 2022, https://www.cbsnews.com/baltimore/news/new-signage-to-be-installed-near-south-mountain-linking-battle-sites/ Obligatory disclaimer. The company I work for has done consulting work for Preservation Maryland and I conducted an interpretive reconnaissance survey for them for the Falling Waters Battlefield. However, I have not done any work on the South Mountain Battlefield, and all my visits have been as a tourist.