You’re reading History’s Confluences, which features historical research, trip reports, book reviews, and public history opinions and analyses.

Two weeks ago, two lanterns sat just outside my window, their dual flames flickering in the night. They served as a tribute to two other lanterns that hung in the belltower of Old North Church in Boston 250 years ago on April 18, 1775. The lights signaled to local Patriot forces that a British expedition was crossing the Charles River on a mission to capture the weapons and ammunition held in the town of Concord.1 Thanks to the lanterns and the efforts of Paul Revere, William Dawes, Samuel Prescott and other messengers, local militia were able to prepare for the British advance.2 The Battles of Lexington and Concord were fought the next day, marking the beginning of the American Revolutionary War.

The lanterns outside my window were part of a broader effort called “Two Lights for Tomorrow: A Nationwide Call to Action.” By commemorating the 250th anniversary of the signal raised in Old North Church, the goal, as described by VA250 (the state organization leading the semiquincentennial planning in Virginia), was to use “imagery of that shining light 250 years ago as a uniting call to action today for our fellow citizens, no matter where they are, to commemorate and remind ourselves that our history is about working together for a better tomorrow.”3

There were many people who played a role in the birth of the United States. Some are commemorated by poems, others by movies, tv shows, and the occasional Broadway musical. But for many, the only recognition they receive is when a historian finds their name on an old muster roll, pension application, letter, or obituary. Still, even if a participant in those events isn’t well known, that doesn’t change what they did and the impact they had. The people who helped spread the word of the British advance that April evening, or who fought in the Battles of Lexington and Concord the following day, all played a role in making history, even if they didn’t know it at the time. As the flames in the lanterns danced in the night, it was hard not to reflect on their stories.

I also thought of the people far away from Massachusetts. Those living elsewhere in the Thirteen Colonies who spent those two April days unaware of that events were taking place that would shape the rest of their lives.

A Sound Carried by the Wind

Much of my life has been spent in places connected to the struggle for American independence. Philadelphia, where I was born, needs no introduction. The Declaration of Independence and the Constitution were both signed in the City of Brotherly Love, which served as the nation’s capital for most of the Revolutionary War.4 Springfield Township, just outside Philadelphia and where I grew up, is also connected to the birth of the United States, even if the township itself didn’t incorporate until 1901.5 In 1777, the soldiers of the Continental Army marched through the area on their way to attack a British force in Germantown (it didn’t go well for the Patriots).6 A short time afterwards, the British made their way through the same area to drive the Continental Army out of their positions on the Edge Hill ridge (it didn’t go well for the British).7 Williamsburg, Virginia, where I attended college, was the center of the struggle between Virginia Patriots and John Murray, 4th Earl of Dunmore (also known as Lord Dunmore), the royal governor. Alexandria, Virginia, where I live now, was also a hive of revolutionary activity (not to mention that George Washington lived just down the road at Mount Vernon and also owned a town house in the city).

The people who called these places home in 1775 all played a role in shaping the story of the early years of the United States. Patriot or Loyalist, free, enslaved, or indentured, young and old, they all contributed in ways big or small, and regardless of whether their efforts succeeded or failed.

Yet, while many people in these areas had been involved in organizing or protesting against British policies (or, if they were Loyalists, finding ways to support the Crown), the events of April 18 and 19, 1775 occurred completely outside of their control. For those living in Williamsburg, Philadelphia, Alexandria, and on the farms and small settlements that what would one day become Springfield, the two April days would have passed without any sense that something earth-shattering had occurred. While the first gun fired at the Battle of Lexington has often been called “The Shot Heard ‘Round the World,” it took time for the noise of that shot to reach people outside of Massachusetts.

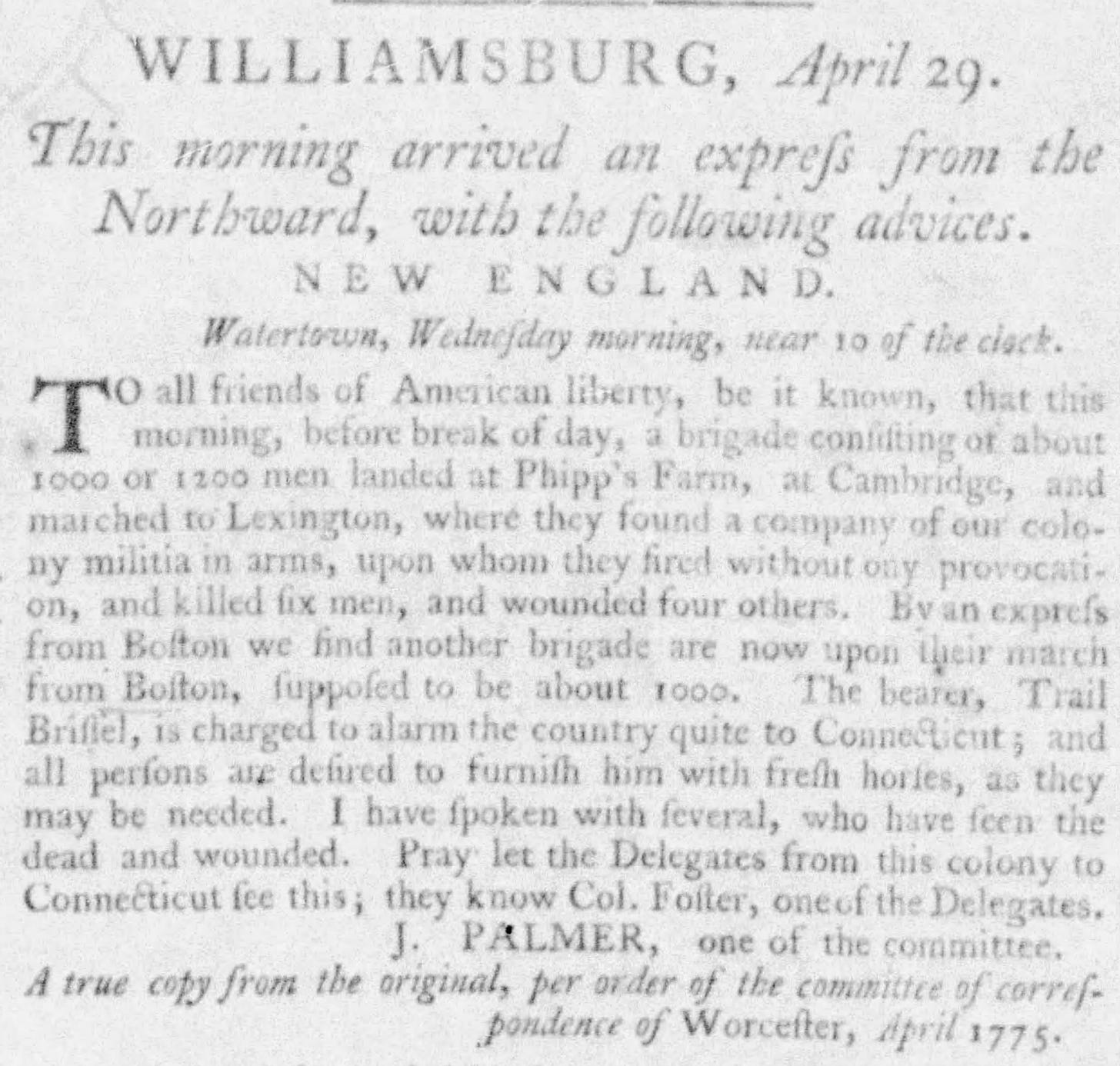

Understanding what had happened was another matter entirely. As news of the clash between the local militia and British regulars spread across the Thirteen Colonies in the days and weeks that followed the battles, people had to determine what exactly had happened and whose stories they could trust. Both George Washington and Thomas Jefferson alluded to the the rumors and conflicting accounts of the events in Massachusetts. “That such an action has happened is undoubted, tho’ perhaps the circumstances may not yet have reached us with truth,” Jefferson noted in a letter.8 Washington wrote to a friend “From the best accounts I have been able to collect of that affair; indeed from every one, I believe the fact, stripped of all colouring, to be plainly this…” indicating that he had to sift through several different versions of events.9

As it became clear what had happened, people throughout the Thirteen Colonies reacted. Militia units in New England rushed towards Boston, while militia units elsewhere in the colonies drilled and trained with increased earnestness. Tempers were high on both sides and thoughts of additional violence and potential recriminations occupied the minds of many. “This accident has cut off our last hopes of reconciliation, and a phrenzy of revenge seems to have seized all ranks of people” Jefferson noted.10 Hearing the news of the battles, Nicholas Cresswell, a Loyalist, wrote in his diary “I hope it will prove that the English have killed several thousand of the Yankees.”11 In Virginia, news of the battles did nothing to help the decaying relations between local Patriots and the royal governor. As his position grew more precarious, Lord Dunmore threatened to free and arm the Patriots’ enslaved workers and indentured servants. Enslavers denounced Dunmore while enslaved people throughout Virginia cheered him. That November, when the governor made good on his threat, many enslaved people took him up on his offer, seeing it as their best chance to escape slavery and secure their freedom.12

The Battles of Lexington and Concord brought an escalation in the conflict between crown and colonies. While many people shaped the story of those April days, many others had to live with the consequences. The war disrupted the lives, placed homes at at risk, and compelled thousands of people to march off to enlist, some never to return. Many must have felt a loss of control even as they took action to try and secure the best possible for future for themselves as their families. Conversely, many of the people who played a role on April 18 and April 19 found themselves on the sidelines for much of the rest of the struggle for independence. No matter how active a person was during the war, the vast majority of what happened still occurred outside of their control.

Is History Against Us All?

While I worked on editing this post, the series finale of Wolf Hall: Mirror and the Light aired in the United States. The show, which chronicles the rise and fall of Henry VIII’s chief minister Thomas Cromwell, couldn’t have less to do with the American Revolution, but there’s a line in the final episode that has stuck with me. Cromwell, imprisoned and knowing he’s only a few days away from the executioner’s ax, chats with his long-time enemy Stephen Gardiner about King Henry VIII’s new wife, Catherine Howard. “History is against her,” Cromwell muses. “I fear it is against us all,” Gardiner sadly replies.

The study of history is a humbling experience. Reading about the past, you come to realize that no one, no matter how powerful, is free from the consequences of events beyond their control. The future is not a blank canvas, but a series of imperfect options that we must chose between based on the limited information we have available to us. Sometimes our best efforts end in failure (just ask the Loyalists). Our lives are impacted, often unexpectedly and unpredictably, by the actions of others and events in the natural world.

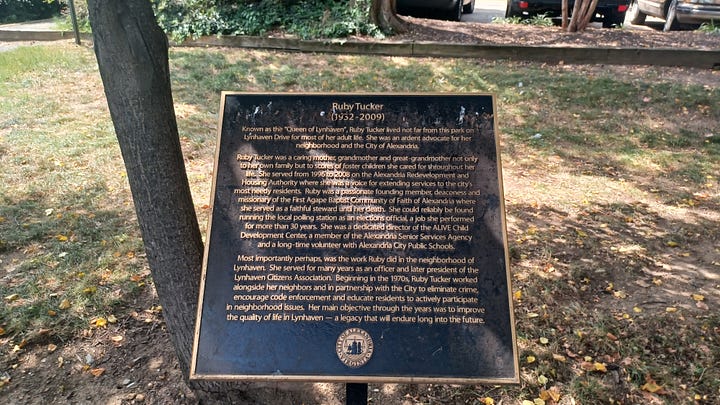

Given all that, it’s easy to feel hopeless. In many ways, history is indeed against us. But within the historical record are also stories of countless people who, working alone or with others, were able to make a difference despite the challenges and setbacks they faced. Sometimes they made a positive change on a national level; other times they made it at a local or individual level. In my corner of Alexandria, the names of several parks pay tribute to long-time community activists who spent decades building coalitions to fight the disinvestment, flooding, neglectful landlords, violence, and open-air drug markets that plagued the community.13 While the area still faces some challenges today, the open-air drug markets are gone, the flooding issue has been mitigated, and people can walk around at night without fear. It’s a great place to live, and residents today have people like Ruby Tucker, Shirley Tyler and their allies to thank for it. Our lives are better because of their actions.

Self-Evident

Staring at those two lights, what stuck in my mind was the many people, locally, nationally, and internationally, who were able impact the course of history. George Washington, James Armistead Lafayette, Margaret Corbin, James Forten, Casimir Pulaski, Deborah Sampson, and Tewahongalahkon (just to name a few) all had their lives impacted and limited by forces outside their control, but that didn’t stop them from helping to shape the course of human events. In much the same way, we all make a difference. We all impact the people and the world around us, and we all leave a legacy. Even if we can’t achieve every dream or fix every problem, and even if we don’t make the correct choice every time, history shows that its within our power to leave this Earth at least a little better then we found it.

So keep those lanterns lit.

Portions of this essay came from content I wrote for the Alexandria Historical Society

All views expressed in this article are my own and do not represent the views of any of my employers, past or present.

“Old North Church,” National Park Service, last updated February 6, 2025, https://www.nps.gov/bost/learn/historyculture/onc.htm

Robert Middlekauff, The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763-1789, (New York, Oxford University Press, 2005), pg. 274-275.

“Two Lights for Tomorrow: A Nationwide Call to Action,” VA250, (accessed on April 22, 2025), https://va250.org/two-lights/

And for much of George Washington and John Adam’s presidencies as well.

“About Springfield,” Springfield Township, Montgomery County Pennsylvania, (accessed on April 20, 2025), https://www.springfieldmontco.org/information/about-springfield/

Michael C. Harris, Germantown: A Military History of the Battle for Philadelphia October 4, 1777, (El Dorado Hills, Savas Beatie, 2023), pg. 248.

Robert N. Fanelli, “The 2nd Connecticut Regiment at Edge Hill,” Journal of the American Revolution, June 15, 2021, https://allthingsliberty.com/2021/06/the-2nd-connecticut-regiment-at-edge-hill/, “Revolutionary War Battles,” George Washington’s Mount Vernon, (accessed on April 18, 2025), https://www.mountvernon.org/george-washington/the-revolutionary-war/washingtons-revolutionary-war-battles

“From Thomas Jefferson to William Small, 7 May 1775,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-01-02-0103. [Original source: The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, vol. 1, 1760–1776, ed. Julian P. Boyd. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1950, pp. 165–167.]

“From George Washington to George William Fairfax, 31 May 1775,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/02-10-02-0281. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Colonial Series, vol. 10, 21 March 1774 – 15 June 1775, ed. W. W. Abbot and Dorothy Twohig. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1995, pp. 367–368.]

From Thomas Jefferson to William Small, 7 May 1775,”

Erin Sterner, “The Journal of Nicholas Cresswell, Part 2,” Emerging Revolutionary War Era, March 20, 2020, https://emergingrevolutionarywar.org/2020/03/20/the-journal-of-nicholas-cresswell-part-2/

Alan Taylor, American Revolutions: A Continental History, 1750-1804, (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2016) pg. 147-148.

Alice P. Morgan, “Tyler, Shirley,” Living Legends of Alexandria, (accessed on April 25, 2025), https://alexandrialegends.org/shirley-tyler/; Rosa Byrd oral history interview conducted by Francesco De Salvatore in Alexandria, VA, 2023 05 11, from the Alexandria Oral History Archive, https://media.alexandriava.gov/docs-archives/historic/info/history/oralhistorygailliotedandshirley.pdf