You’re reading History’s Confluences, which features historical research, trip reports, book reviews, and public history opinions and analyses.

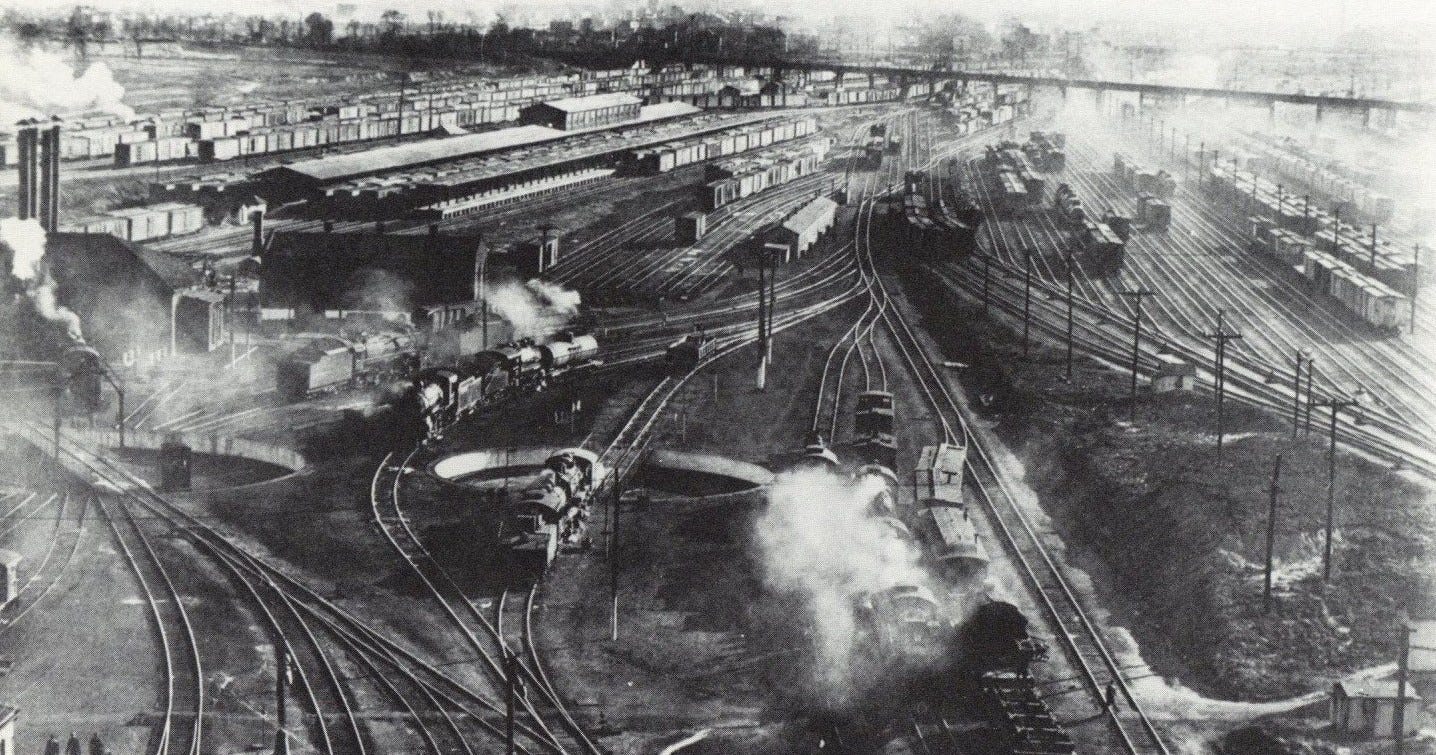

In the northeast corner of Alexandria, Virginia, down the road from where I live, there was once a massive rail yard. Thousands of trains passed through each year as crews inspected and rerouted the cars to ensure they made it to their final destinations. The rail yard was a major job creator for the region. Working there could be dangerous, but the good pay meant that it was an attractive option for many. Those who worked in the yard built communities nearby where they raised their children; some of whom went to work at the the yard themselves when they grew up. Known as “the Gateway between the North and South,” its official name was Potomac Yard.

I’ve been working on the railroad

Potomac Yard opened in 1906. Workers were tasked with properly sorting the cars and attaching them to the correct locomotives to complete their journeys. At its greatest extent, there was about 136 miles of track within the yard alongside many different support buildings.1 In her report on the yard, former Alexandria Archaeologist Francine W. Bromberg describes its layout:

The yard was divided into two main areas—a northbound classification yard and a southbound classification yard. In the northbound yard, freight destined for the north came into the yard, was classified and made up into trains for the northern markets. The routine was the same in the southbound yard. Trains would come in, climb what was called the hump, and be directed toward the appropriate track to form outbound trains by the throwing of switches. Initially, gravity took the cars down the hump with brakemen riding on the sides of the cars and manually putting on the brakes (Griffin 2005; Mullen 2007).

While the main function was freight classification, the yard had numerous support buildings and facilities. These included an 800-foot long transfer shed to consolidate freight from cars that were not full, facilities for pit inspection of the cars, a 12-stall round house and engine house for repairs and maintenance, and a 135-foot high coal tipple that could load over 1500 tons of coal per day to satisfy the needs of the steam locomotives. There were also facilities for feeding and resting livestock in transit. In addition, a huge icing facility could service 500 cars of perishable goods per day with ice manufactured by the Mutual Ice Company of Alexandria.2

All of this fit into a piece of land that was only about two and a half to three miles long and fairly narrow.3

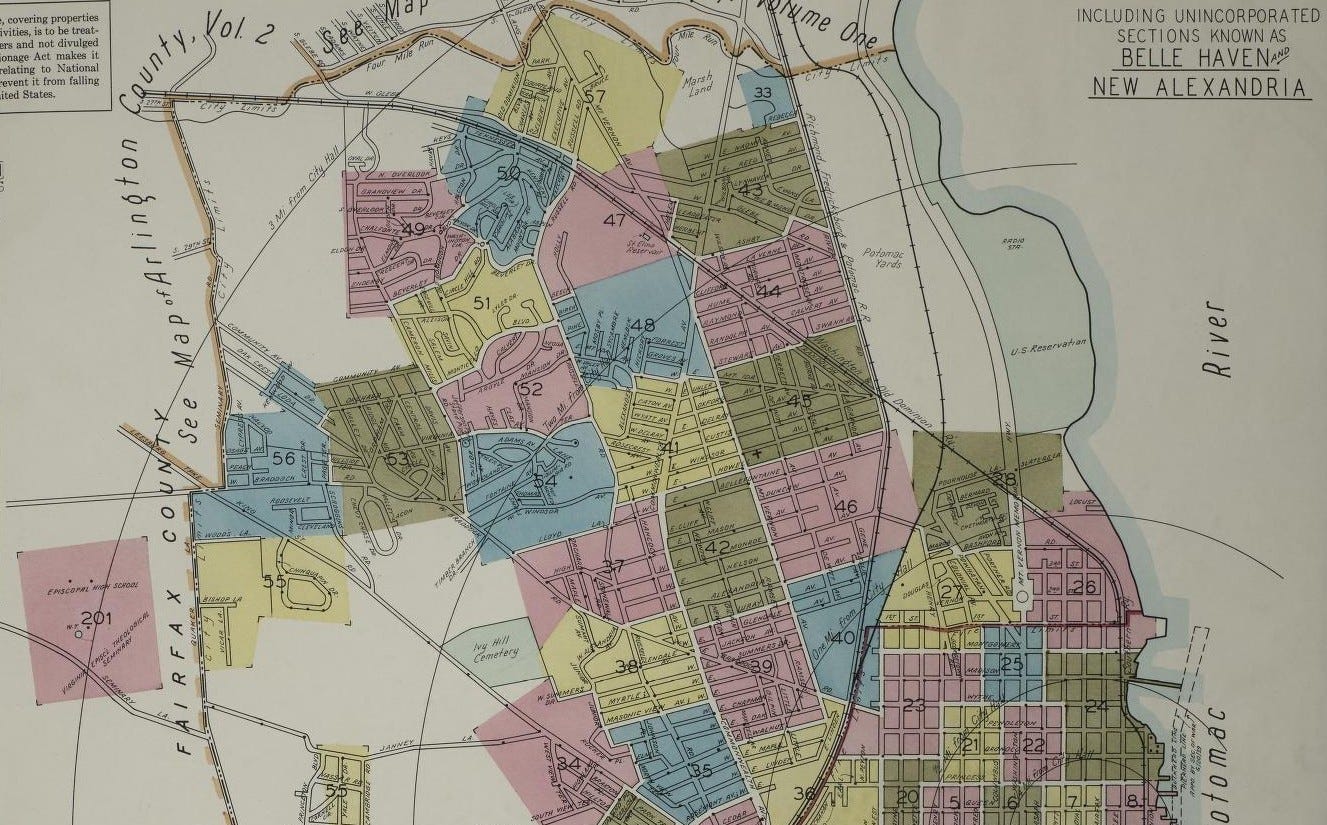

As the rail yard grew, so did the nearby communities of Del Ray and St. Elmo; which was incorporated as the Town of Potomac in 1908. Many workers and their families lived in these communities, and working at the yard was sometimes became a family tradition. When asked why he applied for a job at Potomac Yard, former employee Phelan Tyler simply replied, “My father worked there.”4

Beyond providing a source of employment, Potomac Yard shaped Northeast Alexandria in other ways. Edward Gailliot, who grew up in Del Ray, recalled that local residents would use the shift change whistles to mark time even if they weren’t railroad workers. "Be home by the second whistle," his mother would tell him.5 Gailliot also noted, "there was always black smoke over Potomac Yards," and that the loud noises of the train cars being moved and shuffled could be heard all over the area.6 Most residents, it seemed, eventually got used to the noise.

Working in the yard could be a dangerous activity. Howard Beach, a former Potomac Yard employee, recalled ‘We had some very bad accidents…it was very numbing to see someone mutilated by a boxcar.”7 Spills, leaks, and derailments were also an issue, and, according to one former employee, ranged from the benign (a train car began leaking orange juice) to the severely hazardous (a car containing nuclear waste derailed).8 Other oral history interviewees mentioned the variety of safety improvements and safety trainings that were put in place over the years to try and mitigate mistakes and injuries.

For a time, the yard’s owners enforced racial segregation at Potomac Yard.9 The yard was later integrated, although I couldn’t find the exact date, and former workers recalled Black and white employees working side by side.

Potomac Yard was originally part of Arlington County, and the City of Alexandria annexed the land it stood on in 1930.10 While much of the debate about annexation focused on the nearby Town of Potomac, newspaper accounts from the time (and historians today) have noted that gaining access to the taxes Potomac Yard paid was probably the city’s main motivation.11 The annexation paid off. According to one former yard superintendent, Potomac Yard was, for many years, Alexandra’s biggest its biggest source of tax revenue.12

Potomac Yard reached its peak during World War II when it employed around 1500 people, and it continued to be an economic powerhouse into the 1980s. “Potomac Yard never stopped changing, from its very beginnings to its end,” historian James McDonald noted13 The operations, the jobs available, and the infrastructure of the yard evolved over time. A cultural resource survey conducted on behalf of the City of Alexandria found that only two buildings from the yards opening in 1906 were still standing in 1989.14 Over the years new technologies, new techniques, and new types of equipment changed the way that work was done in Potomac Yard. Former employee Walter Cabler recalled that the first computer at Potomac Yard was from National Cash Register and was “ten foot long, four or five foot wide, and all of em just full of boards.” The computer required several clerks to operate, but was more efficient then the previous method of writing everything down by hand.15 Yet while Potomac Yard changed and evolved, changes in the outside world eventually forced its closure.

New economic patterns, improved technology, competition from trucks, rising real estate values, taxation issues, and railroad bankruptcies and mergers all played a role in the decision to close the yard.16 The yard didn’t close overnight, but over time fewer trains passed through and even fewer stopped to have their cars sorted. While management promoted a spirit of optimism, many employees began to see the writing on the wall. During the late 1980s and early 1990s, the buildings were torn down, the employees were transferred or laid off, and most of the rails were ripped up.

Many accounts of Potomac Yard end here, but the area’s story continued.

Old Rails Gone

With the end of Potomac Yard as a working rail yard, city officials faced the challenge of determining what was next for the massive space. The area was prime real estate, and local officials were understandably interested in ensuring that it continued to be a source of tax revenue.

The first task was to clean up the site. Decades of industrial activity, including diesel fuel leaks and coal ash dumping, meant that Potomac Yard was heavily polluted.17 The area was declared a Superfund site, and remediation activities began.

There were many different ideas about site’s future. City planners in the 1980s originally came up with a plan for a mixed-use neighborhood. However, in 1992, Virginia Governor L. Douglas Wilder proposed building a football stadium at the site, only to shelve the idea in the fact of local pushback and legislative skepticism.18 A plan for a convention center proposed the following year also ended up being scrapped.

Eventually, city planners gave approval to build a strip mall in the northern section of Potomac Yard to serve as a 20-year stopgap for the site until it could be redeveloped as a mixed-use residential and commercial area (other sections of the former rail yard would be developed in the interim). In 1997, the Potomac Yard Center opened to the public.19 While some of the inaugural shops, like Sports Authority and Shoppers, are no longer present, others including PetSmart, Staples, and Target are still serving customers today.

News reports from the time show a divided response from Alexandrians to the new shopping center. Some critics worried about the possibility of increased traffic, while others were disappointed that the soccer field and skating rink amenities present in previous development plans were missing.20 Some felt that the shopping center was ugly. However, others spoke in favor of the new stores. Nearby resident Catherine Fudge declared, “It’s great. It’s about time. I’ve lived in this neighborhood all my life, and it’s great that they’re finally doing something with the railroad yards.”21 President of the Lynhaven Civic Association and civic activist Ruby Tucker, who lived in a neighborhood across the street from the strip mall, praised it as a source of jobs and an easy, walkable shopping option for her and her neighbors.22

When the shopping center opened, its critics might have taken comfort that its expected 20-year shelf life meant that it wouldn’t be a permanent addition to the city. However, even by 1999, its popularity was causing some developers to acknowledge that the timeline for the shopping center’s retirement might need to be adjusted.23 Today, its been nearly 30 years since Potomac Yard Center debuted, and the stores are still there.

Starting in the 2000s, a series of office buildings, apartments, and rowhouses began to arise south of the shopping center. Changes occurred in the areas surrounding Potomac Yards too. Many of the houses built near the former rail yard began to exponentially rise in value. Most of the homes in Ruby Tucker’s Lynhaven neighborhood, which The Washington Post referred to as “a lower-middle class neighborhood” in 1997, are now valued at over $500,000 according to Zillow.24 In Del Ray, a growing number of the houses built during Potomac Yard’s prime years as a rail yard now sell for over a million dollars.

In the past decade, local residents have watched as two new major projects arose in Potomac Yard, the Potomac Yard Metro Station and the Virginia Tech Innovation Campus. The Potomac Yard Metro had been a dream of many city residents, elected officials, and planners since at least the 1990s.25 It finally opened in 2023. The Virginia Tech Innovation Campus was unveiled alongside the announcement that Amazon would be opening a new headquarters in nearby Crystal City.26 While Amazon ended up scaling back some of its plans for the area, the Innovation Campus began welcoming students in January 2025.27 Both projects had their share of controversy, but now that both are up and running it seems that the most residents have accepted them as part of the Potomac Yard landscape.28

The same cannot be said of the other recent large development project proposed for Potomac Yard. In late 2023, Virginia Governor Glenn Youngkin, the mayor and city council of Alexandria, and representatives of Monumental Sports unveiled their plan for Potomac Yard’s future, a mixed-used development anchored by a sports arena that would replace the shopping center and fill up much of the currently vacant land around the Metro.29 The arena would serve as the new home of the Washington Capitals hockey team and the Washington Wizards basketball team. In some ways, this was a continuation of long-term plans that called for the redevelopment of that section of Potomac Yards into a dense mixed-use area.30 However, having the arena as the centerpiece of the development immediately proved controversial. Concerns ranged from increased traffic on game days to Monumental Sports unfairly receiving taxpayer subsidies. Lawmakers outside of the Alexandria area also raised concerns about funneling significant funds to the project. Widespread local opposition hindered the plan’s progress, and when Senator L. Louise Lucas in the Virginia Senate removed language authorizing the arena from the annual budget bill, the effort fell apart.31

Past is Present

Given all the development and changes, one might be forgiven in thinking that Potomac Yard’s railroad history has been forgotten. While the land looks unrecognizable compared to 50 years ago, the City of Alexandria has done a great job researching and interpreting the area’s past. Cultural resource studies, archeological reports and oral histories conducted by the city provide an extensive documentary record of the Potomac Yard story. A historic trail with interpretive signage runs through Potomac Yard, featuring historical images, relevant facts, and quotes. The signs are placed along a biking/walking path in a linear park and are located near playgrounds and sports facilities to better catch the eye of residents. Most of the signage is also positioned so that visitors might look up from the text and see a train speeding by.

Potomac Yards is still a place of trains and railroads. In addition to the Metro trains that stop at Potomac Yard Station, Amtrak and Virginia Railway Express passenger trains and CSX freight trains continue to pass through. For anyone living in or near Potomac Yards, seeing and hearing trains is still an everyday occurrence, and the number of trains is planned to increase in the coming years. In 2019, the Commonwealth of Virginia announced an agreement to buy part of CSX’s right of way on the rail corridor from DC to Richmond.32 The state, working with Amtrak, will be building a new bridge over the Potomac River and making track updates to improve travel times. The ultimate goal is hourly service from DC to Richmond at speeds faster than driving. If those plans work out, rail will be a part of Potomac Yard for decades to come.

All abroad for the future

Former Potomac Yard superintendent Jack McGinley noted in an oral history, "Potomac Yard had outused its usefulness as a railroad facility. But if you go out there today, you will see that it has great utilization for other purposes."33 As someone who moved to the Potomac Yard area fairly recently, am I disappointed that I never got to see the rail yard? A little, but I think that McGinley was right about the need for Potomac Yard to be utilized for new purposes. Today, it’s a pretty nice place to live. The area is very walkable, the Metro makes getting into Washington DC a breeze, the shopping center is convenient, and Potomac Yard is a great place to go running and learn about the area’s past. The history of Potomac Yard is the history of change, and it seems that there’s more change in the area’s future.

Despite all the development in Potomac Yard, there are still several large empty lots, particularly around the Metro. The future of these sections is still up in the air, and there are a lot of opinions about what should happen to them (my vote for is for dense, transit-friendly, mixed-use development…but that’s an article for another time). What isn’t up for debate is that the area’s history is very much still being written. The rail yard may be gone, but recent chapters of Potomac Yard’s history, from the multiple fights over building a stadium/arena to the effort to get the new Metro station up and running show that the story of this place is far from over.

The future

Today Potomac Yard continues to a place of railroads and trains while also offering shopping, dining, and living opportunities. The area’s past is thoughtfully interpreted. While the yard itself no longer exist, there are many opportunities to engage with its complex and engaging history.

A history that is still evolving.

Interested in learning more about Potomac Yard’s railroad history? Check out this video by scholar (and former coworker of mine) James McDonald.

Note: Portions of this post were adapted from articles and social media posts I’ve written for the Alexandria Historical Society.

All views expressed in this article are my own and do not represent the views of any of my employers, past or present.

Francine W. Bromberg, “The History of Potomac Yard: A Transportation Corridor through Time,” in North Potomac Yard Small Area Plan, (City of Alexandria, 2017), pg. A23. https://media.alexandriava.gov/content/planning/SAPs/NorthPotomacYardSAPCurrent.pdf

Bromberg, “The History of Potomac Yard,” pg. A23.

Bromberg, “The History of Potomac Yard, pg. A23.

Phelan Tyler oral history interview conducted by Jennifer Henry in Alexandria VA, 2006 09 17, from the Alexandria Oral History Archive, pg. 5.

Edward and Shirley Gailliot oral history interview conducted by Mary Baumann and Pam Cressey in Alexandria, VA, 2004 11 13, from the Alexandria Oral History Archive, pg. 12. https://media.alexandriava.gov/docs-archives/historic/info/history/oralhistorygailliotedandshirley.pdf

Edward and Shirley Gailliot oral history, pg. 13.

Howard Truslov Beach oral history interview conducted by Susan Callegari in Alexandria VA, 2005 12 14, from the Alexandria Oral History Archive, pg. 12.

Walter Cable oral history interview conducted by Amanda Ognibene in Asburn VA, 2006 12 10, from the Alexandria Oral History Archive, pg. 16-17. https://media.alexandriava.gov/docs-archives/historic/info/history/oralhistorycablewalter.pdf

Bromberg, “The History of Potomac Yard,” pg. A23.

Ted Pulliam, Historic Alexandria: An Illustrated History, (San Antonio: Historical Publishing Network, 2011), pg. 52. Note: In the 1950s Potomac Yard expanded into a section of Arlington County north of Four Mile Run (modern-day Crystal City).

“Possession of Potomac Yards Held Real Issue in Alexandria’s Annexation Fight,” The Washington Post, October 16, 1927, (accessed on ProQuest Historical Newspapers); Michael Lee Pope, “The Hidden History of Del Ray,” Alexandria Gazette Packet, March 22, 2019, https://www.alexandriagazette.com/news/2019/mar/22/hidden-history-del-ray/?template_preference=desktop

Norman Gomlak, “Past Becomes Future,” Alexandria Journal, November 29, 1988, in William C. Sheild, Potomac Yard, VA: The Gateway Between the North and the South: Book 2, (Richmond: Fredericksburg and Potomac Railroad Historical Society, Inc, 2015), pg. 632.

James McDonald, “Potomac Yard: Constant Motion…Constant Change,” Presentation to the Washington DC Chapter National Railway Historical Society, February 17, 2023, video link.

Mark K. Walker and Marilyn Harpers, Potomac Yard Inventory of Cultural Resources, (Alexandria: Engineering Science, 1989), pg. 8.

Walter Cable oral history interview, pg. 9-10.

James McDonald, “Potomac Yard: Constant Motion…Constant Change.”

“Nicholas Horrock, “South Potomac Yard Area Certified as Safe,” Alexandria Gazette Packet, May 3, 2012, https://www.connectionnewspapers.com/news/2012/may/03/south-potomac-yard-area-certified-safe/; “Environmental Services for Potomac Yard Redevelopment Project,” Geosyntec consultants, (accessed on March 23, 2025), https://www.geosyntec.com/projects/item/779-environmental-services-for-potomac-yard-redevelopment-project

John F. Harris and Robert F. Howe, “Stadium will Spark Boom, Wilder Vows,” The Washington Post, August 15, 1992 (accessed on ProQuest Historical Newspapers).

Margaret Webb Pressler, “Potomac Yard’s Monumental Appeal,” The Washington Post, October 13, 1997 (accessed on ProQuest Historical Newspapers).

Eric L. Wee, “Mixed Reviews for Strip Mall at Potomac Yard,” The Washington Post, October 27, 1977 (accessed on ProQuest Historical Newspapers).

Pressler, “Potomac Yard’s Monumental Appeal.”

Wee, “Mixed Reviews for Strip Mall at Potomac Yard.”

Leef Smith, “Latest Potomac Yard Proposal Includes Houses, Shops, Hotel,” The Washington Post, June 11, 1999, (accessed on ProQuest Historical Newspapers).

Wee, “Mixed Reviews for Strip Mall at Potomac Yard.”

Jordan Pascale, “Metro’s Potomac Yard Station Opens, Anchoring A Quickly Growing Neighborhood, DCist, May 19, 2023, https://dcist.com/story/23/05/19/metros-potomac-yard-station-opens/

Susan Svrluga, “Amazon arrival spurs Virginia Tech to build technology campus in Northern Virginia,” The Washington Post, November 13, 2018, https://www.washingtonpost.com/education/2018/11/14/amazon-hq-arrival-spurs-virginia-tech-build-technology-campus-northern-virginia/

Vernon Miles, “Virginia Tech Innovation Campus celebrates grand opening in Potomac Yard neighborhood,” ALXnow, February 28, 2025, https://www.alxnow.com/2025/02/28/virginia-tech-innovation-campus-celebrates-grand-opening-in-potomac-yard-neighborhood/

And as a frequent user of the Potomac Yard Metro Station, I’m thrilled that it’s here.

Sam Fortier, Teo Armus, and Laura Vozzella, “Monumental, Youngkin announce deal to move Caps, Wizards to Virginia,” The Washington Post, December 13, 2023, https://www.washingtonpost.com/dc-md-va/2023/12/13/capitals-wizards-move-alexandria-potomac-yard/

North Potomac Yard Small Area Plan, (City of Alexandria, 2017), https://media.alexandriava.gov/content/planning/SAPs/NorthPotomacYardSAPCurrent.pdf

Laura Vozzella, Gregory S. Schneider and Teo Armus, “Virginia Sen. L. Louise Lucas deals another blow to arena project,” The Washington Post, February 22, 2024, https://www.washingtonpost.com/dc-md-va/2024/02/22/virginia-arena-bill-lucas-senate/; Staff “Monumental Sports Arena Negotiations End,” Alexandria Living Magazine, March 27, 2024, https://alexandrialivingmagazine.com/news/monumental-sports-arena-negotiations-end/

“Press Release: A new Long Bridge, infrastructure to transform passenger, commuter, and freight rail in the Commonwealth” Virginia Passenger Rail Authority, December 19, 2019, https://vapassengerrailauthority.org/virginia-and-csx-announce-landmark-rail-agreement/

Jack McGinley oral history interview conducted by Jen Hembree in Alexandria, VA, 2007 04 14, from the Alexandria Oral History Archive, pg. 17. https://media.alexandriava.gov/docs-archives/historic/info/history/oralhistorygailliotedandshirley.pdf