Located along the banks of the Potomac River, a few miles south of Washington, DC, is Alexandria, Virginia. Formally chartered by the Houses of Burgesses, Virginia’s colonial legislature, in 1749, the city turned 275 years old in 2024

To commemorate Alexandria’s birthday, the Alexandria Historical Society (AHS) compiled some of our social media posts (lightly edited) in this article. These posts are not meant to be comprehensive history or even capture Alexandria’s most significant events but rather reflect the stories that resonated with the AHS board, our members, and our social media followers. While some of these stories are light-hearted, others deal with serious and sometimes painful topics.

Braddock, the Bad Guest?

In 1755, during the French and Indian War, Alexandria merchant John Carlyle and his wife Sarah Carlyle found themselves reluctant hosts when General Edward Braddock began using their house as his headquarters. The general and his officers planned to march their army to the Forks of the Ohio (present-day Pittsburgh) to drive out the French garrison there, but first, they needed to get organized in Alexandria. Soon, the house was filled with officers, civilian officials, and anyone else who had business with the general.

Although Braddock was friendly, John Carlyle grew to detest the general, calling him "very indolent, [a] slave to his passions, women and wine." In Carlyle’s eyes, Braddock and his staff had taken advantage of his hospitality, wrecked his house and furniture, and, in general, been lousy houseguests.

The presence of Braddock and his fellow officers also meant more work for Carlyle House's enslaved workers. Now, they had to cook for and clean up after the general and his staff in addition to the forced labor they already performed for the Carlyle family. (A story recounts Braddock making a rude joke to an enslaved woman named Penny. While Penny did exist, historians believe the story of Braddock’s conversation with her to be fictional.).

Braddock paid Carlyle 50 pounds for the use of his house. Whether or not he was aware of his host's feelings toward him is unclear. Still, Braddock had other things to worry about. The campaign against the French had to be planned, an alliance with the powerful Haudenosaunee Confederacy needed to be forged, and meetings with colonial officials needed to occur for the expedition to be successful. While Carlyle wasn’t pleased with Braddock’s manners, he was excited that his home played host to “The Grandest Congress,” a meeting between Braddock and five colonial governors to discuss strategy for the upcoming campaign.

So with all that planning, was Braddock’s Expedition a success?

I like Lincoln

The 1860 presidential election was one of the most consequential in United States history. Four candidates battled for the presidency amid heated debates about the expansion of slavery into the western territories.

In 1860, Virginia law limited the right to vote to white men over the age of 21. In contrast to today's secret ballot, voting was handled "viva voce," meaning that voters were expected to speak their choice in front of the public. In 1860, voters in Alexandria also submitted a signed ballot as part of the election process. Voting for an unpopular candidate was a potentially dangerous decision.

While Abraham Lincoln ultimately won the 1860 presidential election, he only received a grand total of two votes in Alexandria City plus 12 votes in Alexandria County (present-day Arlington County). One of these voters was Andrew Wylie. Born in Pennsylvania, Wylie married an Alexandrian and eventually moved to the Port City to practice law.

Casting a vote for Lincoln proved to be a challenge. Wylie had to write to a friend in Wheeling, Virginia, for a Lincoln ballot, and the election officials initially hesitated to record his vote. News about Wylie's choice soon spread, and he began receiving threats. One day, a mob confronted him in Alexandria and followed him home.

The threats against Wylie highlight how unpopular Lincoln was in the eyes of many white Southerners. In the aftermath of the election, many in the South refused to accept Lincoln's victory. Calls for secession, fueled by pro-slavery extremists, increased, and within a year, the country plunged into civil war.

In 1861, Wylie moved to Washington, D.C. Two years later, President Lincoln appointed him an associate justice on the Supreme Court of the District of Columbia. He served in this role until retiring in 1885. Later, he gave an interview to The Alexandria Gazette about his experiences casting a vote for Lincoln in antebellum Alexandria.

Wylie’s story and his interview with The Alexandria Gazette can be found in the Fall 1999 issue of The Alexandria Chronicle, which is available on the publications page of the AHS website.

Unionists in the Port City

“No person shall vote or hold office under this constitution who has held office under the so-called Confederate government or under any rebellious State government, or who has been a member of the so-called Confederate congress.” -1864 Virginia Constitution

That isn’t a typo. In the middle of the Civil War, a Virginia constitution was created that was explicitly anti-Confederacy. Lost Cause mythology presents the idea that Virginians were united in supporting the Confederacy. In reality, there were many Virginians who opposed secession, thought the Confederacy was illegitimate, and considered Robert E. Lee, Jefferson Davis, and other Confederate leaders to be traitors. In 1861, prominent Virginia Unionists gathered in Wheeling, Virginia (later West Virginia), to form the Restored Government of Virginia. After West Virginia became a state in 1863, the Restored Government moved to Alexandria, meaning that the city was, for a time, the capital of the Old Dominion.

In 1864, while meeting in Alexandria, the Restored Government wrote a new constitution for the state. In addition to disenfranchising people serving the Confederacy, the 1864 Constitution also abolished slavery in the commonwealth, declaring, “the general assembly shall make no law establishing slavery or recognizing property in human beings.” However, even though many Black Virginians were serving as soldiers, spies, or workers for the Union army, the new constitution continued to restrict voting rights to white men.

Recently, the Virginia Department of Historic Resources added the former Bank of Potomac building at 415 Prince Street to the Virginia Landmarks Register. Built in 1807, this building served as the executive office and residence of Francis H. Pierpont during his time as governor of the Restored Government of Virginia. This designation recognizes the role the building played during this key part of Alexandria’s history and the complex story of the Civil War in Virginia. The structure is privately owned and is not open to the public but can be viewed from the sidewalk.

Murder Pure and Simple

Each year on April 23, the city remembers the life of Joseph McCoy. On April 23, 1897, a mob of over 500 lynched McCoy, a Black Alexandrian.

McCoy grew up in Alexandria. His grandmother, Cecilia McCoy, raised him in The Bottoms neighborhood, and he attended Roberts Memorial Chapel (Roberts Memorial United Methodist Church).

On the day of his murder, the mob broke into the jail where McCoy was held (accused but not convicted of a crime), overpowered the officers there, and dragged him outside. They beat, shot, and hanged him from a lamppost. McCoy was only 19 years old.

In the aftermath of McCoy’s lynching, many white Alexandrians applauded the mob. According to some accounts, the murderers included several city leaders and well-connected citizens. The Alexandria Gazette called the lynching a tragedy but placed all the blame on McCoy. By contrast, The Richmond Planet, an African American newspaper, declared, “This act was in violation of the laws of Virginia and the statutes of the United States. It was murder pure and simple, and as it was premeditated, executed with precision, it was murder of the first degree.”

McCoy was buried in an unmarked grave at Penny Hill Cemetery. During the funeral service, Reverend William Gaines prayed, “I trust that the time will soon come when all people will realize the fact that the same judgment which they measure to others will be measured to them at the bar of God.”

McCoy’s death was one of two documented lynchings in Alexandria. In 1899, a mob murdered Benjamin Thomas, another Black Alexandrian. Lynchings were a key tool in maintaining white supremacy in the post-Reconstruction era. Ida B. Wells, who worked to document and denounce these hate crimes, noted that lynching victims were often successful African Americans or were those who challenged the status quo.

No one was ever convicted of McCoy’s murder.

Working on the Railroad

Potomac Yard, located in Northeast Alexandria, takes its name from the rail yard that once stood in this section of the city. Known as “The Gateway Between the North and the South,” hundreds of trains passed through each day during its peak.

As the rail yard grew, so did the nearby communities of Del Ray and St. Elmo, which formed the Town of Potomac in 1908. Many workers and their families lived in these communities, and some later participated in oral histories conducted by the city. Edward Gailliot recalled that local residents, even if they weren't railyard workers, would use the shift change whistles to mark time. "Be home by the second whistle," his mother would tell him. Gailliot also noted, "there was always black smoke over Potomac Yards," and that the loud noises of the train cars being moved and shuffled could be heard around the area. Working the yard could be a dangerous activity, with several former workers describing in oral histories some of the injuries that occurred.

A confluence of factors eventually led to the closure of the yard in the 1980s, but that wasn’t the end of Potomac Yard’s story. As Jack McGinley, the yard’s last superintendent, noted in an oral history, "Potomac Yard had outused its usefulness as a railroad facility. But if you go out there today, you will see that it has great utilization for other purposes."

McGinley was right. Today, Potomac Yard is home to a shopping center with a Target, Best Buy, Chipotle, and several other stores and restaurants. Many Alexandrians live in rowhouses or apartments built on where the rails used to be. The new Virginia Tech Innovation Campus is under construction, and the Potomac Yard Metro Station opened last year.

The area's history isn't forgotten either. Signs in Potomac Yard Park tell the story of the former rail yard. Meanwhile, freight and passenger trains continue to run along the remaining tracks, continuing to connect North and South. It's a new chapter for Potomac Yard as its history continues to be written.

Creating a Community

In 1905, Laura Watson became a land developer. She and her husband, Charles Watson, had purchased property in present-day Arlandria along Four Mile Run in 1870 to be used for his “Rag and Bone” business, an early reuse and recycling operation. Four years later, however, Charles Watson died, leaving her a widow. Watson worked as a domestic servant, enduring long hours and low pay to support her family. She ensured her children received an education, and one son became an attorney after graduating from Howard University. At the start of the 20th century, she and her sons decided that her land could be put to a new purpose.

The previous few decades had seen the rise of Jim Crow in Virginia and the passage of racist laws designed to exclude African Americans from political and economic opportunities. Poll taxes and onerous restrictions prevented many from voting, and “white-only” public facilities blocked access to many schools and libraries. This discrimination extended to housing. New subdivisions were going up throughout Northern Virginia, but the vast majority were restricted to white buyers.

As Black Alexandrians, Watson and her family understood the many restrictions facing their community. By dividing up her land into individual plots (hence the term subdivision), Watson and her family offered Black Alexandrians a chance to own land, something that was denied to them in the emerging subdivisions north and west of the Port City.

Watson called the community Sunnyside. While she continued to live at 518 Gibbon Street in the Old Town section of Alexandria, she ensured that her family’s legacy was represented in the new community by naming the streets after her sons and husband.

The historical record suggests that profits from the sale of her land allowed Watson to retire from her job. She lived in her home on Gibbon Street until she passed away in 1924. Today, a plaque at Sunnyside in Alexandria’s Arlandria neighborhood pays tribute to her and her family’s legacy.

Making the Library Public for Everyone.

In 1939, the Alexandria Library on Queen Street was the only public library in the city. Although supported by taxes paid by all adult Alexandrians, it was open to white Alexandrians only. Samuel Wilbert Tucker, a 26-year-old Alexandria lawyer, was determined to change this.

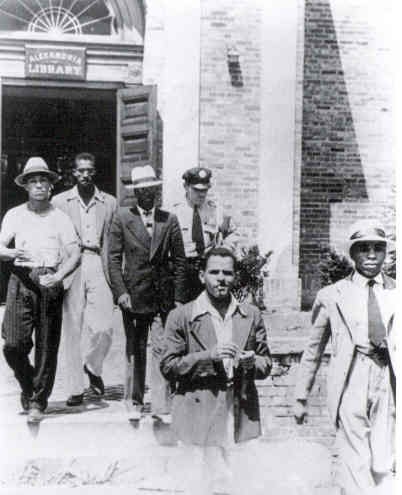

On August 21, 1939, William Evans, Otto L. Tucker, Edward Gaddis, Morris Murray, and Clarence Strange walked into the library and requested library cards. After the librarian told them that library cards were not issued to African Americans, they found seats in the library and began to read. Library staff called the police. As the officers led the five men out of the library, they were met with a crowd of around 300 people and reporters from several newspapers. Samuel Tucker had planned the protest with the five men and ensured that the media covered the event.

In response, Alexandria constructed the Robert H. Robinson Library. The library was for Black Alexandrians but lacked many of the resources of the library on Queen Street. The books were second-hand donations, and the building had a dirt floor. While the Robinson Library provided access to books and periodicals for many Alexandrians, it was a far cry from integration, and Tucker refused to patronize it. The five men who protested at the library on Queen Street were charged with "disorderly conduct." However, the judge declined to issue a verdict, leaving them in legal limbo, neither guilty nor innocent in the eyes of the law.

Starting in 1959 and continuing into the early 1960s, the city began to desegregate its library facilities. The process was completed by 1962. Today, the former Robinson Branch building is home to the Alexandria Black History Museum.

In 2019, the charges against William Evans, Otto L. Tucker, Edward Gaddis, Morris Murray, and Clarence Strange were formally dismissed. Samuel Tucker went on to have a long career as a lawyer, arguing several cases in front of the Supreme Court. Today, the Samuel W. Tucker Elementary School is named after the man who orchestrated the protest and helped lead the fight against Jim Crow in Alexandria.

In 2024, Dr. Brenda Mitchell-Powell, AHS board member and author of the book Public in Name Only: The 1939 Alexandria Library Sit-In Demonstration, sat down for a podcast about the sit-in. You can listen to the podcast here: Part I, Part II.

Birth of the Torpedo Factory

The US Navy began construction of Alexandria's iconic Torpedo Factory just one day after Armistice Day. World War I was ending, but the military still decided to build the facility and manufacture munitions there. The plant produced torpedoes until 1923 (one or two years after this photo was taken) and then served as a munitions storage space.

In the late 1930s, as storm clouds once more gathered over Europe and Asia, the government decided to resume torpedo production at the plant. The factory employed thousands of workers, and the demand for employees brought many new residents to Alexandria, which, in turn, prompted the creation of new housing developments. The workforce of the torpedo factory was integrated, although African Americans and their families still had to contend with the segregation and racism of Jim Crow Alexandria. Class prejudice was also present, as some long-time Alexandria residents looked down on the new arrivals.

According to one source, by the time production ceased in 1946, over 9,000 torpedoes had been produced. The workers at the Torpedo Factory played an important role in defeating the Axis. Not all employees remained at the factory for the entire conflict. Some enlisted and served on the front lines.

After the war, the Torpedo Factory served as a Federal Records Center. In 1969, the City of Alexandria purchased the building, and, in 1974, after years of citizen activism, it reopened as the Torpedo Factory Art Center. Today, the Torpedo Factory features beautiful works of art made by talented artists and is the home of the Alexandria Archaeology Museum. While Alexandria might not need a place to manufacture torpedoes anymore, creativity and openness to change ensured that the Torpedo Factory could be reinvented as a thriving center for history and art.

The Torpedo Factory Art Center is celebrating its 50th anniversary this year and remains a beloved community institution.

Floods lead to Change

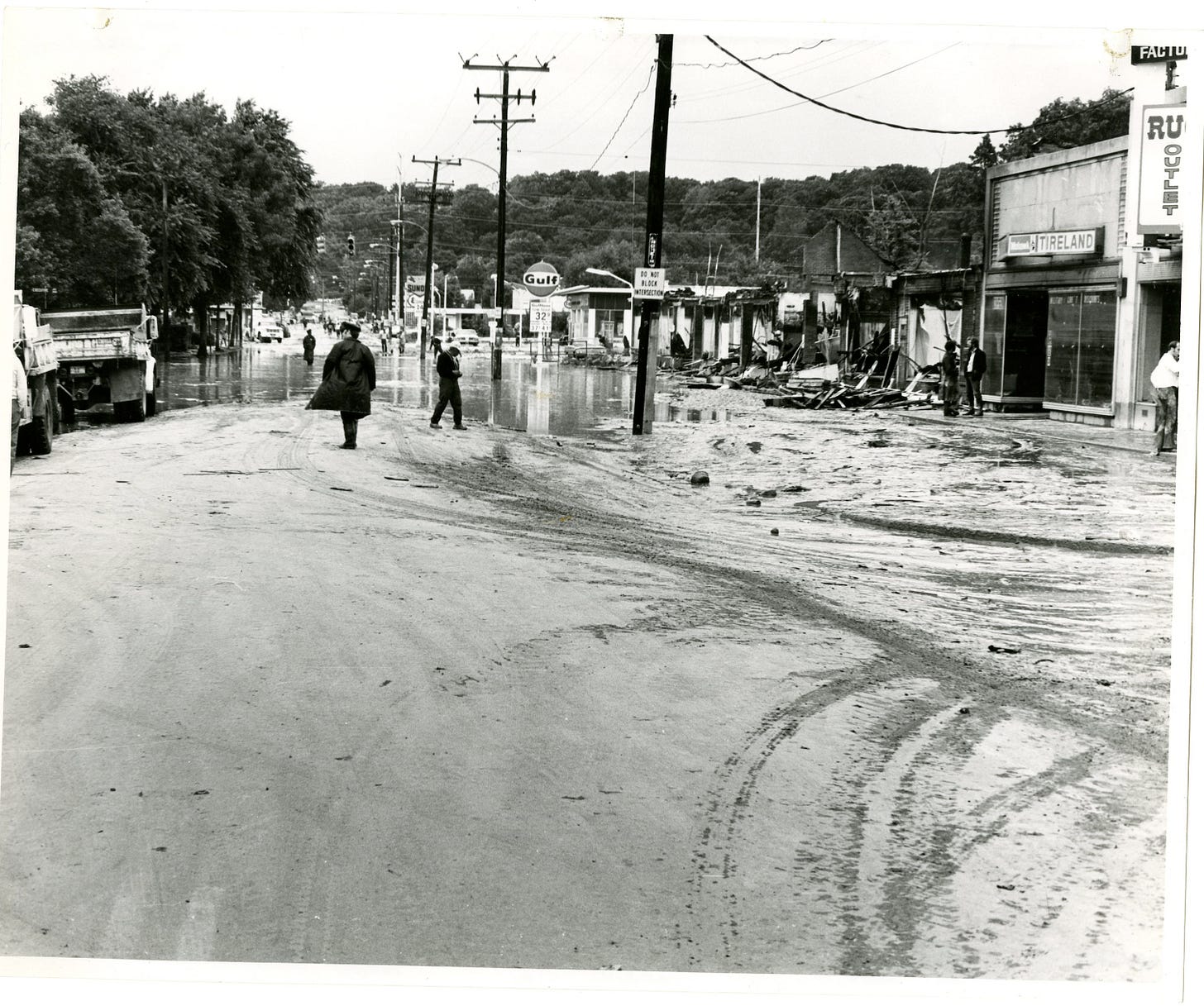

“The Washington area struggled out of one of the worst flood disasters in its history last night,” The Washington Post reported on June 24, 1972. Hurricane Agnes had battered the Washington, DC, area, causing flooding, property damage, and power outages. In Alexandria, the rain caused Four Mile Run to overflow, forcing many residents of the Arlandria neighborhood to evacuate. At least one person in the neighborhood, a resident of Presidential Gardens Apartments, died. Alexandria officials solicited donations for Arlandria residents and set up an immunization station at Mount Vernon Elementary School.

By June 25, it was safe for residents to return. The Washington Post reported, “Shop owners and residents could be seen shoveling mud clumps of cement and other debris from lawns, sidewalks, and storefronts.” Unfortunately, several businesses, including a grocery store and a drugstore, decided it wasn’t worth it to reopen and closed permanently, a significant blow to the community.

“Always the first to feel the brunt of heavy rainfall,” one reporter noted of Arlandria. The destruction of Four Mile Run’s wetlands and the increased suburbanization of Northern Virginia meant that too much water often flowed directly into the creek, causing flooding. As a result, Arlandria experienced multiple severe floods in the twentieth century.

The Arlandria Civic Association was determined to change this. They put pressure on the city and the federal government to find a solution. Eventually, a flood control plan was put in place for Four Mile Run, which included the creation of Four Mile Run Park. The effort took years, during which time Arlandria experienced several more severe floods. After the project’s completion, the rate of flooding declined dramatically. Agnes devastated Arlandria, but the area’s residents, rather than giving up, turned it into a rallying cry for action.

The Sun is Shining on Arlandria

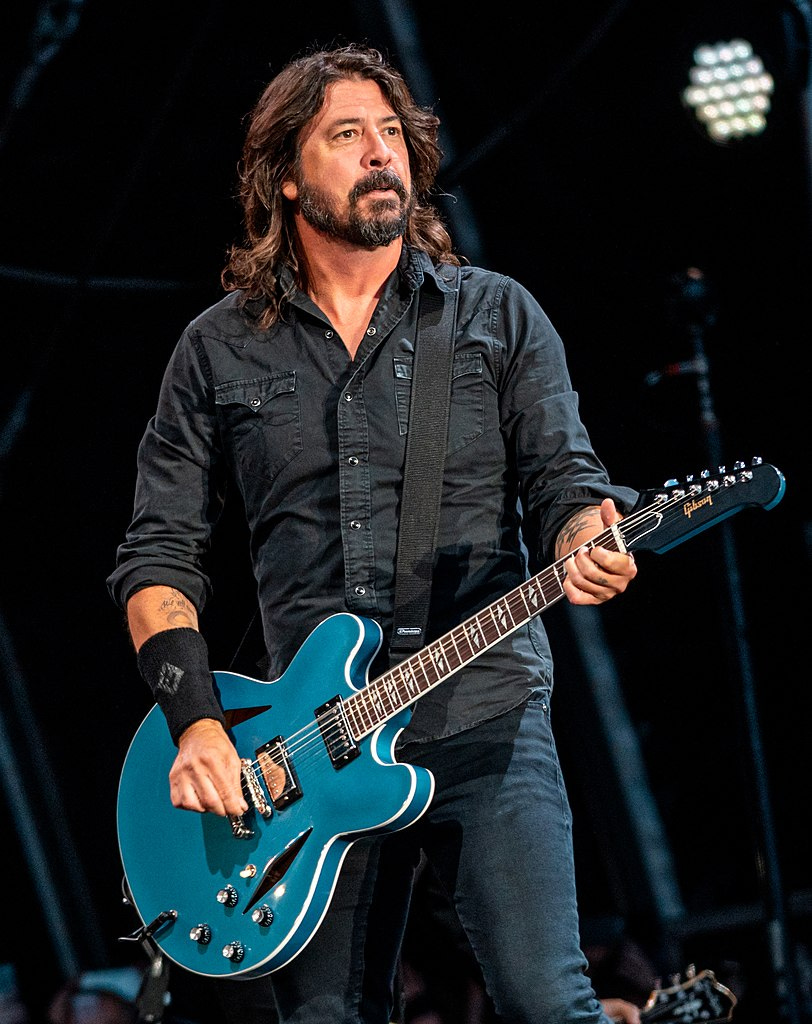

While people today know Dave Grohl as the rock star legend of Nirvana and Foo Fighters fame, there was a time when he was just another student attending school in the Port City. Grohl grew up in Northern Virginia and attended Bishop Ireton High School in Alexandria for a time in the 1980s. The music scene in the DC area inspired Grohl, and he gained experience playing with local bands. After heading out west, Grohl joined an up-and-coming rock band called Nirvana, and the rest, as they say, is history.

Despite his fame, Grohl never forgot about Northern Virginia. When Nirvana was touring in the DC area, his mother, Virginia, offered her house to the band as a place to relax and chill between performances. In the 1990s, after Nirvana dissolved in the aftermath of Kurt Cobain's suicide, Grohl returned to Northern Virginia. His current band, Foo Fighters, recorded several songs in the Alexandria area, and two of their songs reference the Arlandria section of the city, "Headwires" and "Arlandria." As Grohl once told an interviewer, "Arlandria is where my house was when I moved back to Virginia... I always go back to Virginia when things get too out of control."

While rocking out is not what many people picture when they think about Alexandria's history, Grohl is one of several noteworthy musicians from the city's more recent past. Jim Morrison of The Doors, and John Phillips, and Cass Elliot of the Mamas & the Papas also spent part of their formative years in the city. Who will be the next musician from Alexandria, Fairfax, or elsewhere in Northern Virginia to make it big? Only time will tell!

Metro comes to Alexandria

On December 17, 1983, Alexandria received an early Christmas present when the Braddock Road, King Street, Eisenhower Avenue, and Huntington stations opened to the public. These new stations, part of an expansion of the Yellow Line, officially connected Alexandria (and the Alexandria section of Fairfax County) to the Metrorail system. Other Alexandria stations followed. The Van Dorn Station on the Blue Line opened in 1991, while the Potomac Yard Station opened last year.

“Metro Extension Opens with Flourish,” The Washington Post declared as the trains began traveling north and south through the Port City. Extending Metro to Alexandria was not without controversy, but when it came time to open the new stations, the city rolled out the welcome mat (pictured). At King Street Station, a bagpiper played and cannons fired to mark the occasion. Around 12,000 passengers utilized the new stations to hop on a Metro train that day.

While Metro (like any transportation system) has experienced challenges over the years, today, it is hard to imagine Alexandria without it. The Metro system has become a part of our city’s history and is used by many locals and out-of-town visitors to travel around and see the area's many historic sites.

Want to learn more about Metro’s history? Back in 2019, the Alexandria Historical Society hosted Dr. Zachary M. Schrag, author of The Great Subway Society: A History of the Washington Metro. Check out his lecture on AHS’s YouTube page.

Preserving the Past

If you’ve ever driven along South Washington Street near the Woodrow Wilson Bridge, you’ve seen the beautiful Contrabands and Freedmen Cemetery Memorial. The memorial marks the final resting place of many of the self-liberated Black Americans who fled slavery to reach freedom behind the Union lines in Alexandria during the Civil War.

The memorial and the preserved cemetery around it exist today thanks to the efforts of Lillie Miller Finklea and her allies. In 1997, Finklea, who had lived in Alexandria ever since she was a child, heard about the cemetery and the threat posed by plans for the new Woodrow Wilson Bridge expansion. Years of neglect and damaging decisions by government officials and private businesses had already disturbed many of the burials there, and Finklea was determined to preserve what remained.

On Memorial Day 1997, Finklea and Louise Massoud, a fellow advocate for historic preservation, hosted a ceremony to lay a wreath at the burial site. The event paid tribute to those laid to rest there and brought press and public attention to the cemetery. To further their efforts, the two formed the Friends of Freedman’s Cemetery and continued to gather support. They built strong relationships with city archaeologists and local historians in order to both protect the site and learn more about the people interred there.

After years of advocacy, their efforts helped prompt the city to acquire the cemetery in order to preserve it. Finklea’s work continued after that, and she helped select the design of the memorial that graces the site today.

Lillie Finklea passed away in December 2022, but her legacy lives on in the cemetery she helped save and the citizens she helped educate and inspire.

Support Local History

In Alexandria and throughout the country, local historical societies work to preserve and share the histories of their communities. They serve as valuable centers of historical knowledge for academic researchers, journalists, public servants, and the general public. While some receive government support, many do not and rely on the contributions, in both time and money, of dedicated supporters and volunteers to stay afloat and advance their missions.

Interested in learning more about Alexandria’s long, complex, and compelling history? The Alexandria Historical Society is active on Facebook, Instagram, and LinkedIn. The society also holds lectures, hosts special events, publishes a journal featuring original research, and provides grants for the study of Northern Virginia history. Want to support the society’s work and receive exclusive discounts? Memberships start at only $20 a year. Interested in learning more about the history of the place you call home? See if your area has a historical society. They’re treasure troves of historical knowledge and valuable community institutions. While not every city is 275 years old, every place has a history that is worth exploring, and your local historical society is a great place to start.