"Fix Your Bayonets"

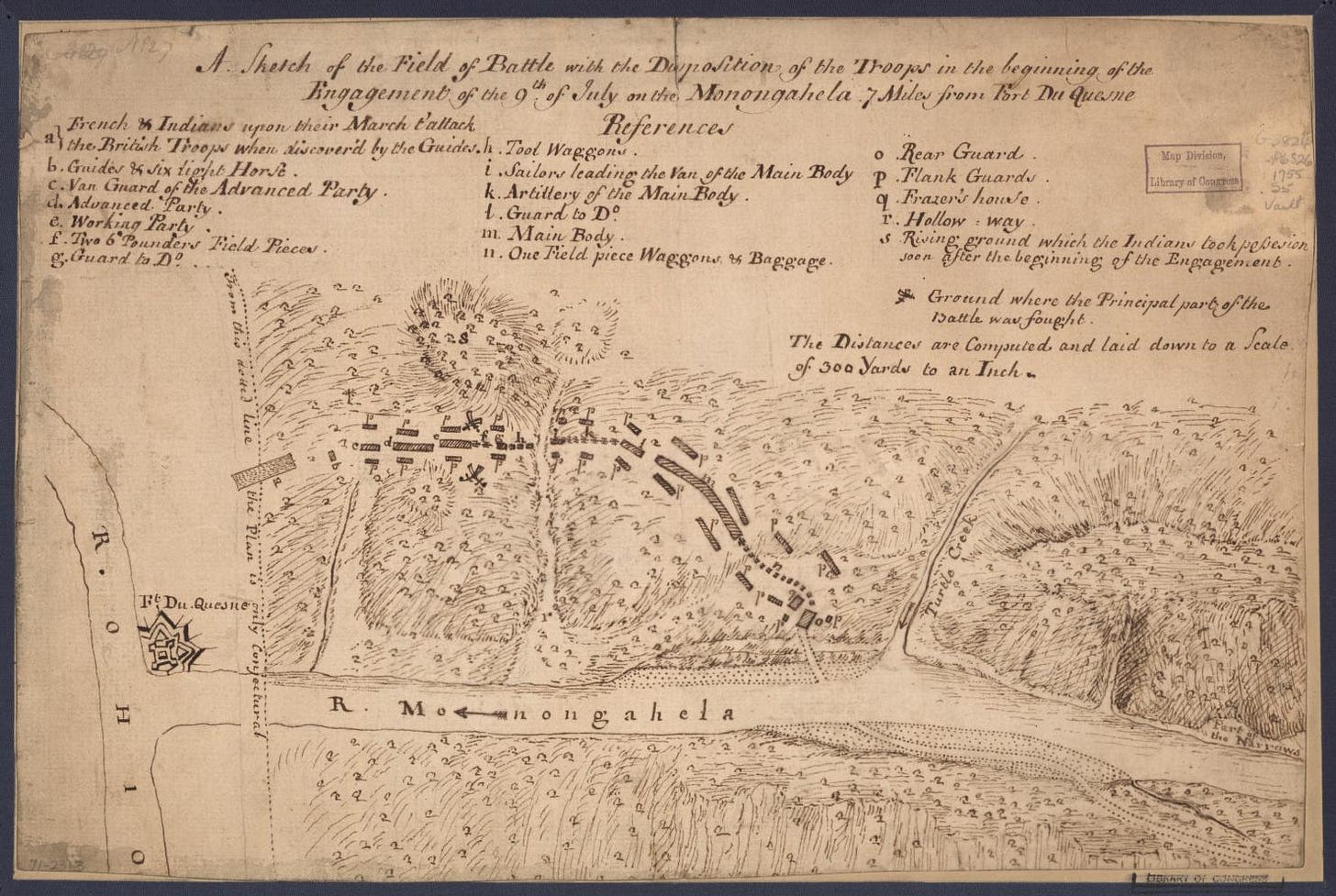

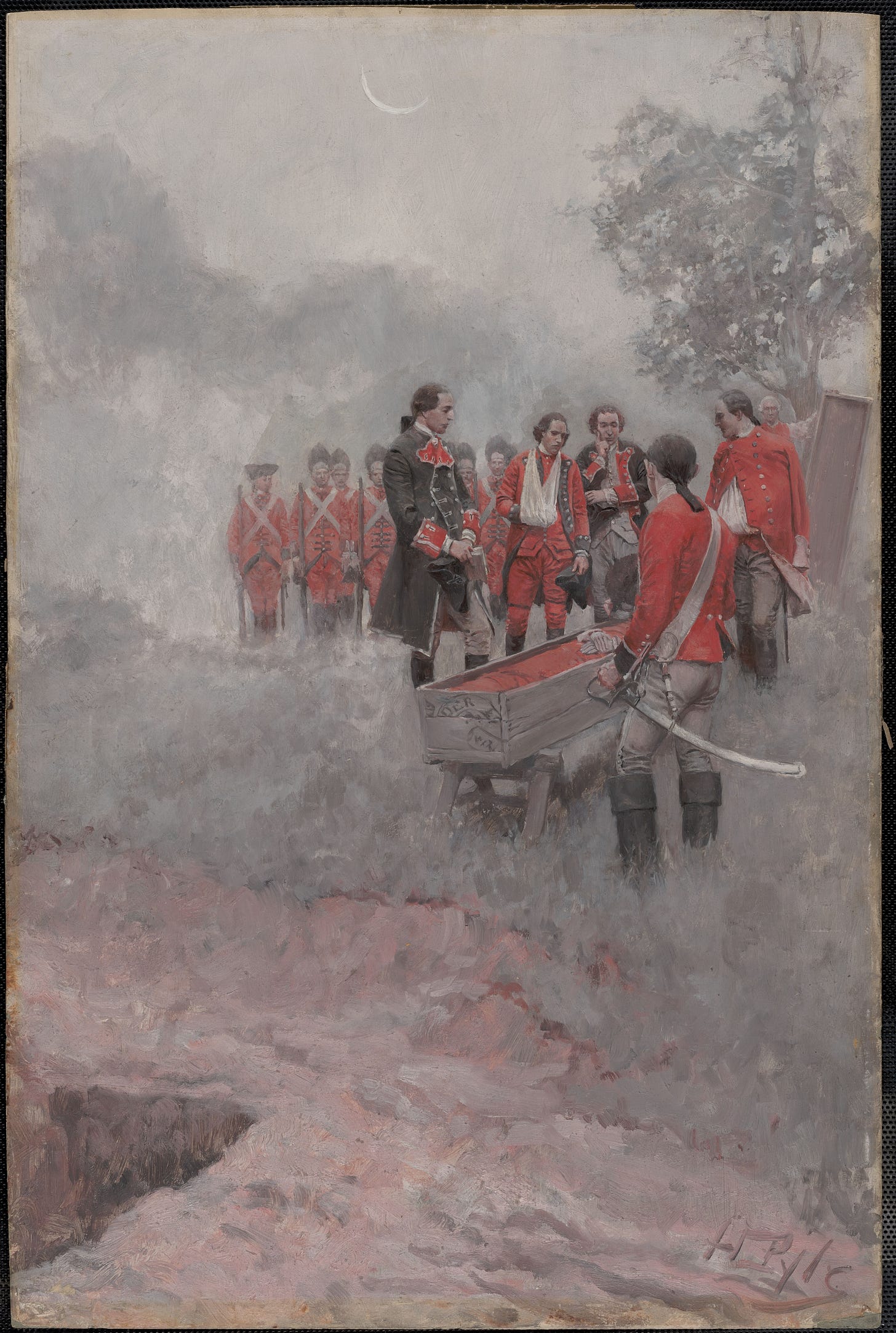

On July 9, 1755, the British army crossed the Monongahela River in present-day western Pennsylvania without incident. The French had been delayed in leaving Fort Duquesne, dashing their plans to ambush General Edward Braddock's army at the river crossing. Undaunted, the French commander Captain Daniel Hyacinthe Liénard de Beaujeu adjusted his plans. The marines and militia under his command would confront the British head-on, while his indigenous allies would fan out to attack the flanks of Braddock's forces.

The two armies met in the afternoon. Initially, the British did well; their volleys devastated the French forces in front of them. Beaujeu fell dead and some of the militia from New France fled. However, flanking fire from the indigenous warriors soon began taking its toll on the British vanguard and they began to fall back...

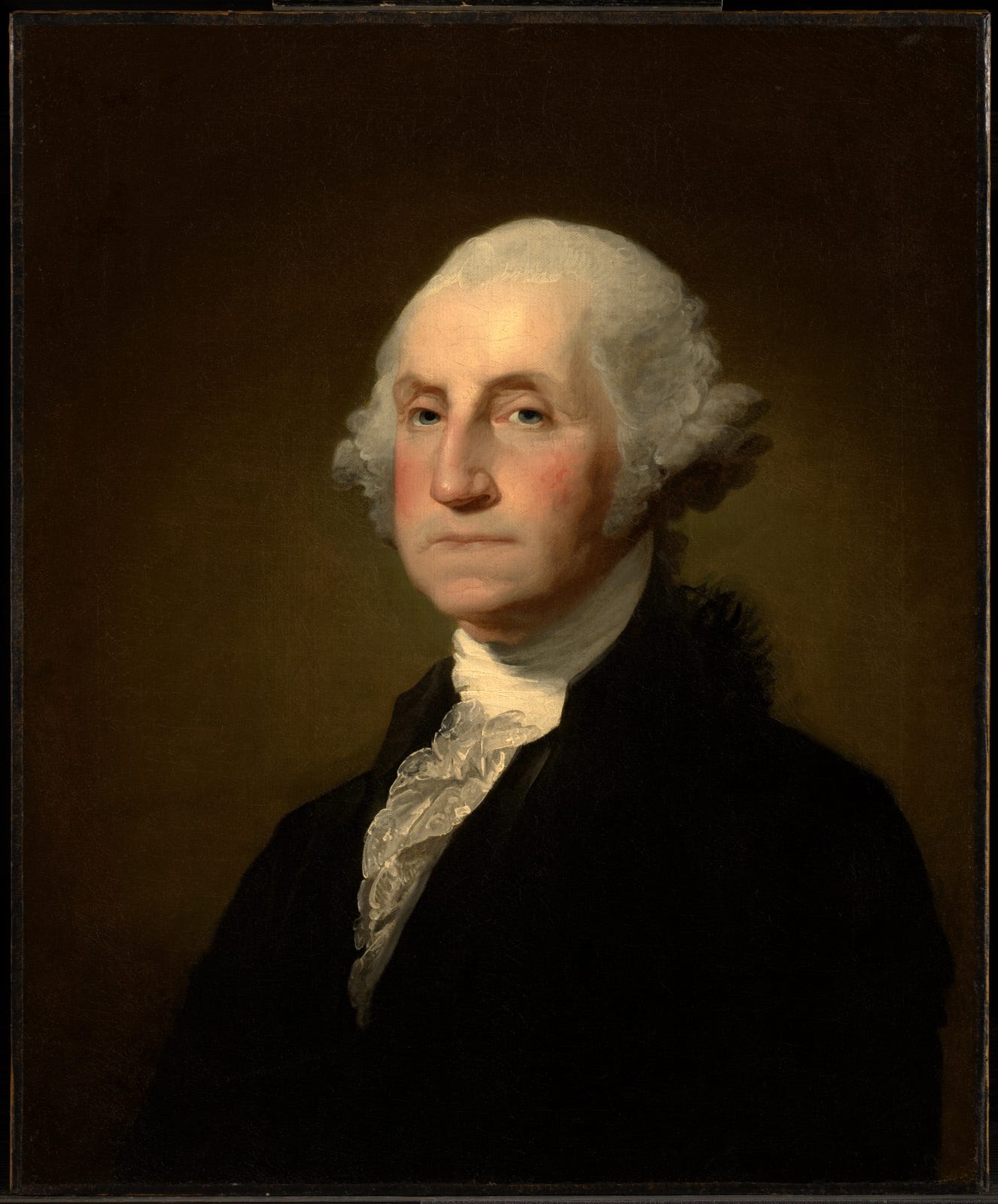

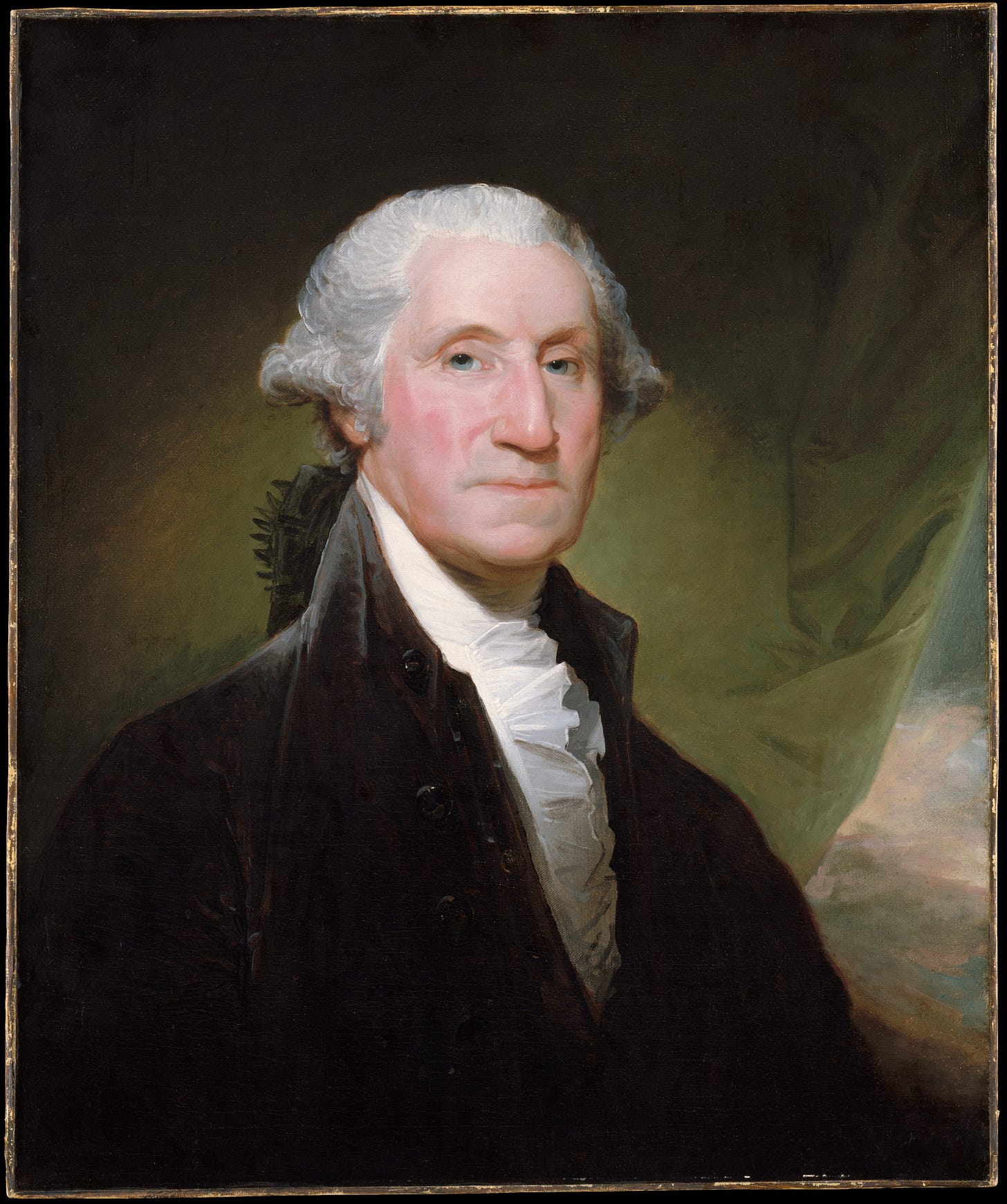

...and collided with other advancing British units. As more and more gunfire erupted from the woods, the British soldiers drew closer and closer together, making them easy targets. Things went from bad to horrible for the British as more and more soldiers fell. As chaos reigned, friendly fire killed many soldiers, including troops from the Thirteen Colonies who were attempting to fight the enemy while taking cover behind rocks and trees rather than staying in tight formation in the open. A young George Washington, serving as a volunteer aide, and several of the other officers begged Braddock "before it was too late... engage the enemy in their own way," but Braddock refused.1

Throughout the battle, Braddock remained on his horse, a tempting target. Numerous bullets pierced his coat before one finally hit its mark, mortally wounding the general. With most of his officers either killed or wounded, the general realized the situation was hopeless, and ordered a retreat. As the shattered army fled the battlefield, the French and indigenous forces kept up a steady fire.

And then I hit “post.”

A battle and a historical society

Braddock’s defeat has its origin in the struggle to control the Forks of the Ohio (present-day Pittsburgh), where the Ohio River is formed by the confluence of the Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers. In the 18th century the British, French, Haudenosaunee, Lenape (Delaware), and Shawnee all claimed jurisdiction over this strategic area. In 1754, a French force expelled a small group of Virginia militia that had been building a stockade at the forks and began building Fort Duquesne at the site.2 In response, Governor Robert Dinwiddie dispatched Virginia troops under the command of Major George Washington. Together with Mingo allies led by Tanaghrisson (known to the English as Half King), the group ambushed an armed French diplomatic party at Jumonville Glen, kicking off the French and Indian War. Tanaghrisson and Washington’s triumph was short-lived. Disagreements between the two leaders prompted Tanaghrisson to lead his men away, and a much larger French force soon marched out and forced the Virginian forces to surrender after a short siege at Fort Necessity.

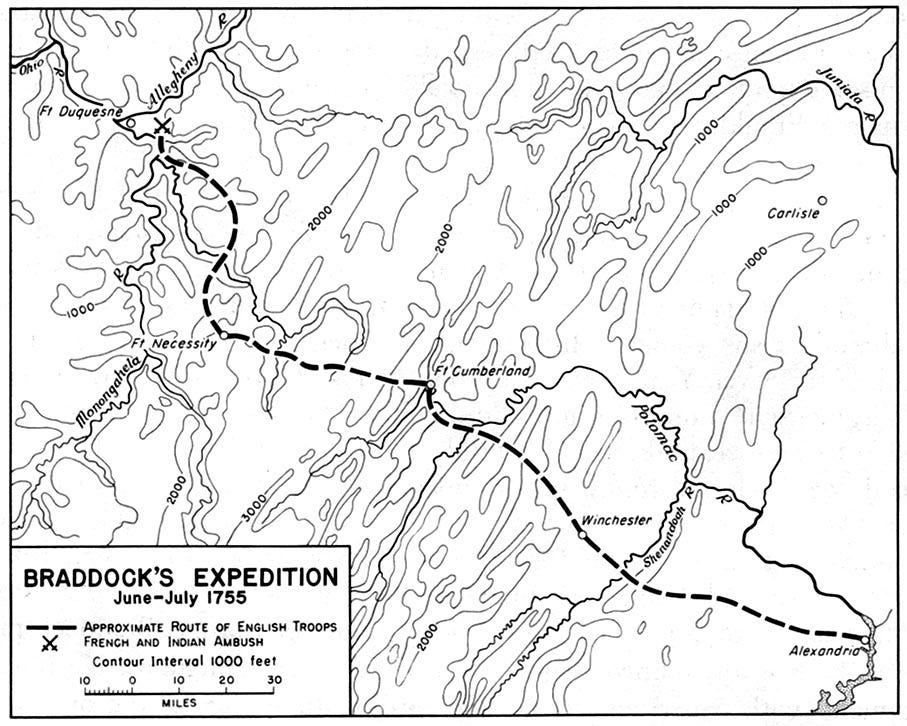

The British government then dispatched a force under General Braddock to take Fort Duquesne. Braddock landed in Virginia, gathered additional troops, marched west, made earnest but ultimately futile attempts to gain the support of local indigenous allies, and made it within striking distance of the fort before being ambushed and defeated. The victorious defenders of Duquesne included French marines, militia from New France, and Ottawa, Ojibwa, Wyandot, Shawnee, Lenape, Mingo, Osage and Otoe warriors.3

The story of Braddock’s failed expedition to the Ohio Valley has obtained almost a mythic status. The grand army, filled with every hope of success, marching to western Pennsylvania only to be mown down by the combined Franco-Indigenous army has captured both popular and scholarly imagination. The fact that so many people who would become famous in later years were present or fought in the battle (such as George Washington, Thomas Gage, Daniel Morgan, and, according to some accounts, Pontiac) also helped it capture interest.

Before marching towards the Forks of the Ohio, Braddock organized his army in Alexandria, Virginia. Located along the banks of the Potomac River just south of Washington DC, the city has grown and changed quite a bit from the relatively small settlement that Braddock saw. Over 200 years after Braddock’s Expedition, the citizens of the city formed the Alexandria Historical Society. The organization is a non-profit that works to support research and interpretation of the city and its past through lectures, published articles, annual history awards, and, most recently, social media. I had the privilege of joining the board of the society in 2022 during a time of post-COVID rebuilding, and as part of my board duties was tasked with rebuilding and enhancing our social media presence. Little did I know when I took the job, that I’d find myself chronicling Braddock’s journey from the Potomac to the Monongahela.

I’m a historian, not an Influencer

The Alexandria Historical Society is an all-volunteer organization, which means there’s no paid social media coordinator person who handles all posting and can stay up to date on trends. Taking over the social media platforms, I had a blank canvas to work with and realized that we needed to prioritize certain goals. Social media is an interpretive tool, so I was able to put some of my interpretive planning training to good use. Since interpretive goals should connect to the organization’s purpose/mission, that was the first place I looked. The Alexandria Historical Society’s purpose is to “promote an active interest in American history and particularly the history of Alexandria and of Virginia” which gave the board and myself a good starting point.4 But the strategies couldn’t just come from the mission, they also had to reflect the current needs of the organization. As discussed previously, the society was in a rebuilding mode, which meant it would be a while before we could go back to regularly publishing new issues of our newsletter and our journal, The Chronicle. Given that, I knew that social media could be a powerful tool to both share stories about Alexandria’s history and promote upcoming events. (I’d be remiss at this point if I didn’t highlight the great work of our president Pam Cressy, our website designer and publications editor Peggy Harlow as well as the rest of my fellow board members. Their jobs were much more difficult than mine). After speaking with the marketing manager at my job who provided many insights and useful advice, I settled on the goals that would guide how we would deploy social media, which the rest of the board approved:

Social media connects followers to the history of Alexandria in all of its diversity and complexity.

Strategies for reaching this goal:

Post content about significant events in the city’s history.

Post content that connects to major city events and holidays.

Post content on noteworthy individuals from the city’s history.

Social media highlights the value of the historical society and encourages membership.

Strategies for reaching this goal:

Use social media to promote AHS events and speakers.

Use social media to promote AHS publications.

Use social media to educator followers about AHS membership options and benefits

Use social media to promote the events and talks of other organizations to strengthen connections with other non-profits and government agencies in the public history field.

Our approach to individual posts was heavily influenced by that taken by the White House Historical Association, the National Museum of African American History and Culture, George Washington’s Mount Vernon Estate, and the National Park Service. All of these organizations pair compelling imagery and video with relevant historical or mission-based information to keep their followers engaged. The National Park Service social media team is also great at working in pop-culture references, puns, and other fun jokes in their posts to make their point. Given our strengths, the board also decided to not try and chase every trend even if it meant hurting our boost rates by the algorithm. Instagram, Facebook, and LinkedIn would be our main platforms and followers on each would see all of our content, while Twitter/X would be used solely to promote events.

A bad day for Braddock, a good day for AHS

Months after this initial strategy was decided on, things had begun to settle in at the historical society as everyone acclimatized to their new roles. In social media, we’d had posts on upcoming talks, a new effort called #HistoryinOurBackyard which encouraged followers to submit posts about historical landmarks or markers that they found in the city, and several well-received pieces on various historical stories. When appropriate, we also deployed pop culture references and humor in the style of National Park Service social media. One especially popular source of humor was modifying quotes from George Washington and using them to promote the historical society.5

Our social media followers grew, and most of the comment responses were positive. Together with our slate of events and new issues of the newsletter and The Chronicle, it was clear that the Alexandria Historical Society was back in business. We did get called Maoists by one irate commentator, but that just goes to show you can’t please everyone.

While brainstorming topics, we came across an upcoming event at Carlyle House, “The ‘Grandest Congress’: The French and Indian War in Alexandria,” which interprets Braddock’s time in Alexandria. Carlyle House served as the general’s headquarters, and the yearly event features a recreation of Braddock’s meeting with several colonial governors as well as reenactors portraying British soldiers and camp followers. This seemed like a great opportunity to both promote the event (you’re welcome, Carlyle House) and do a post about Alexandria’s role in the Braddock campaign. However, after starting to research, I realized that there was too much for one social media post. From this came “From the Potomac to the Monongahela, which ended up being a series of twelve posts about the expedition that took our social media followers on the journey of Braddock and his forces.

Figuring out the frequency of posts was the first challenge. Devoting all social media posts from March through July was a non-starter. We attempt to post around every other day (with some exceptions) and had other events to promote and historical topics to discuss. In the months between the anniversary of Braddock’s arrival in Alexandria and the bloody end of his expedition, the AHS hosted several speakers and our annual history awards. Notable anniversaries during this time included the secession of Virginia, Union troops arriving in the city, Lee’s surrender at Appomattox, and the murder of Joseph McCoy by a lynch mob. There were also holidays and month-long commemorations to acknowledge like Memorial Day, Pride Month, Juneteenth, and Independence Day.

Content was another concern. While much happened during Braddock’s expedition, there were also days when the army simply marched and worked on building the military road from Cumberland to the Monongahela. Likewise, some certain key concepts or decisions would be hard to date. Ultimately, major dates in the campaign were marked whereas other important topics were slotted in as appropriate.

Finding appropriate imagery was another challenge. Visuals are key for social media, particularly Facebook and Instagram, and I couldn’t expect our followers to read a bunch of text without some type of graphic to catch their attention as they scrolled through their feeds. Our licensing budget for social media is $0, so public-domain high-quality images were (and are) the order of the day. That ruled out many iconic paintings of the campaign as they would have required licensing fees. Another factor was time. Licensing and acquiring high-resolution images can take weeks and while in some instances I was able to plan ahead, other times it made more sense to use what was readily available. A copy of George Washington in his Virginia Regiment uniform from the Library of Congress was used instead of one from the original repository. Likewise, an image of Seneca leader, Sagoyewatha (Red Jacket) was used even though he would have been too young (or not have been born depending on the source) to participate in Braddock’s conversations with indigenous leaders. The image of him was high-quality and metadata suggested that he’d approved of the portrait artist’s work. Other images for that post were discarded due to either being too expensive to license, low-quality, or stereotypical/historically inaccurate. Of course, we couldn’t completely avoid historical inaccuracies in the visuals we used, but we tried to find the best public-domain images that we could.

It worked out that while I was working on “From the Potomac to the Monongahela,” I had a chance to visit Wills Creek (Cumberland, Maryland). Fort Cumberland was a major staging area for the campaign and Braddock remained here for a time gathering supplies, meeting with indigenous leaders, and drilling his troops. The fort is long gone but there’s an interpretive trail that follows its perimeter, which I was able to share with the Alexandria Historical Society’s social media followers.

Assessing the campaign

Compared to Braddock’s Expedition “From the Potomac to the Monongahela” was a success (granted, that’s a pretty low bar). Engagement was pretty good, social media followers responded well, and we gained a number of new followers. Still, it didn’t quite get the engagement I was hoping for and the overall engagement with the posts in this series was not very different from our regular posts.

What would we do differently next time? For one, we’d probably devote more posts to Braddock’s time in Alexandria. This would’ve meant front-loading the posts and then doing fewer and fewer as the army got further and further away from the city, but it would have allowed us to dig deeper on topics relating to discipline, recruitment, civilian-military relations, and what 1755 Alexandria looked like. I’d also try and see if I could do any partnership posts with some of the historical sites that commemorate Braddock’s march like the Alleghany Museum, Fort Necessity, and Braddock’s Battlefield Museum. That might have been helpful in expanding our reach and attracting more engagement and followers.

Future social media campaigns will probably be less spread out than this one. The nature of focusing on a story that spanned months meant that some social media followers missed posts, and our content had to include enough of a summary to keep people up to speed. More recently, we did a social media series about when the British captured Alexandria during the War of 1812. That story, from when the British ships were first sighted to when American troops bombarded the withdrawing squadron at the Battle of White House Landing south of the city only took around a week and a half, which meant we could be more concise and there was less chance that people would miss posts.

Braddock lives again… in article form!

With “From the Potomac to the Monongahela” concluding, the historical society decided to combine the various posts into one consolidated story. Initially, I pitched this as going into our newsletter, but the society’s president recommended including it in our journal, The Chronicle. Normally when working on social media content, journal articles are a source for your posts. Here the opposite would be the case, the social media posts would form the backbone of the article’s structure.

Of course, there’s a world of difference between a journal article and social media posts (there’s also a difference between a social media post and a more informal article like this one. The opening paragraphs were pulled from one of the posts, but I still had to make a couple of edits. Footnotes needed to be added and proper section titles inserted. The recaps and intros for many of the posts had to be removed as are some of the opening jokes that I wrote for some of the posts. I will miss this intro from a post that focused on the army’s progress through the forests of western PA and Washington coming down with a bad case of dysentery:

"I don't feel so good. Where's the privy?"

"Good question, George Washington. Even though we're marching through the woods, we need to be deliberate about where we dig our catholes. The National Park Service recommends digging catholes 200 feet away from water sources and the trail. Do you have a plastic bag to pack out your toilet paper?"

"It's the 18th century..."

"It's never too early to start practicing proper backcountry etiquette!"

Still, while some content is lost, much is also gained. Expanding this into an article has provided an excuse to do more research and include materials cut from the original posts. The sections on Alexandria in the new journal article will be significantly expanded and will provide a better glimpse into 1755 Alexandria and how it impacted and was impacted by Braddock’s Expedition.

The article is still being researched and formatted so AHS members will have to wait a bit longer to read it. One thing that I’m very excited about is that as AHS moves towards its 50th anniversary, the article will pay tribute to one of its earliest contributing historians. The second edition of The Chronicle includes two articles by historian Ethelyn Cox about Braddock’s march; one a general campaign retrospective and the other a look at the story of Charlotte Browne, a hospital matron on the campaign, whose diary is a valuable primary source. History is a process of reexamination and revision, so not every old article holds up. However, I’m happy to report that much of what Ethelyn Cox wrote remains accurate and relevant, and her articles will be referenced as footnotes in this upcoming article. If we’re lucky, 50 years from now another author preparing a piece on Braddock for the Alexandria Historical Society will judge this upcoming article worthy of the same treatment.

David Preston, Braddock’s Defeat: The Battle of the Monongahela and the Road to Revolution, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015), pg. 253.

Fred Anderson, Crucible of War: The Seven Years War and the Fate of Empire in British North America, (New York: Vintage Books, 2001), pg. 49.

Colin G. Calloway, The Indian World of George Washington, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018), pg. 110.

“Constitution, April 2003, as amended 27 June 2012, Article II,” The Alexandria Historical Society, https://sites.google.com/view/alexandria-historical-society/about-us/founding-documents?authuser=0

Don’t worry, we made sure that it was clear that the quotes were fake.