The Confederacy and the Slave Trade

A review of "An Unholy Traffic: Slave Trading in the Civil War South"

You’re reading History’s Confluences, which features historical research, trip reports, book reviews, and public history opinions and analyses.

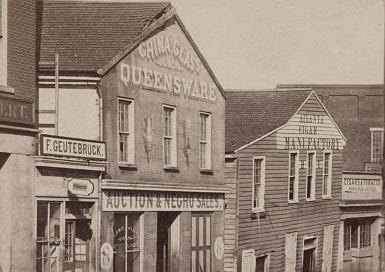

During the first half of the nineteenth century, 1315 Duke Street in Alexandria, Virginia served as the headquarters for a succession of slave trading companies. For decades, the firms that operated the complex imprisoned thousands of men, women, and children before forcibly transporting them to markets in the Deep South. Trafficking in human misery made the slave traders rich.

Thanks to the work of local historians and the Office of Historic of Alexandria, we know a considerable amount about 1315 Duke Street, including how it was finally put out of business.1 On May 24, 1861, the day after Virginia seceded, several Union regiments advanced on Alexandria. Upon reaching the slave-trading pen, the soldiers encountered several enslaved people (sources differ on the exact number).2 The soldiers also encountered a “well-dressed gentleman” who attempted to grab one of the enslaved people and leave.3 The Emancipation Proclamation was still two years away, but the soldiers, perhaps guessing that the belligerent slaveholder was no friend of the Union, chased off the man and liberated all the enslaved people in the building. The Union Army took full possession of the complex and turned it into a military prison for both captured Confederates and disorderly Union soldiers.4 1315 Duke Street’s time as a slave trafficking site was over.

But had the Union Army not occupied Alexandria at the beginning of the war, 1315 Duke Street might have remained in business for a few more years. In An Unholy Traffic: Slave Trading in the Civil War South, Robert Colby, a professor of history at the University of Mississippi, documents in extensive detail the continued existence of the slave trade during the Civil War.5 Despite, or perhaps because of, the uncertainties of war, organized slave-trading thrived throughout the conflict. Colby’s book provides an in-depth examination of how this “unholy traffic” functioned and shines a light on the stories of the enslaved people trapped within it.

Wartime Adaptions

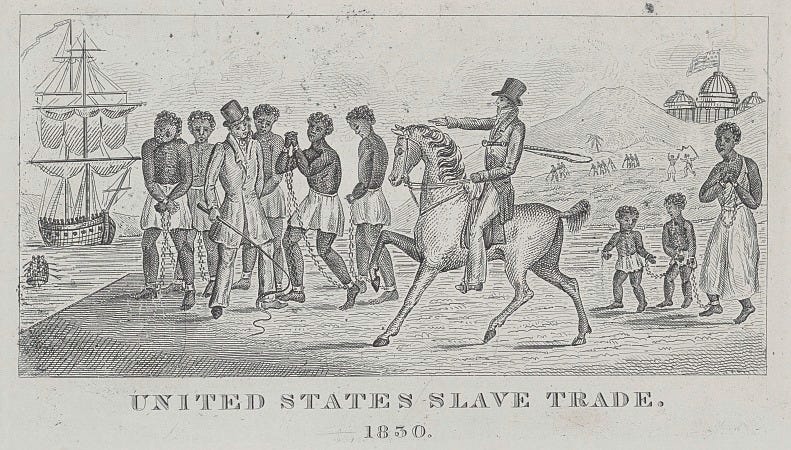

That the slave trade would survive the beginning of the Civil War is not surprising. The highly-lucrative trade enabled the perpetuation and expansion of chattel slavery in the United States, as traders sold enslaved people from the Upper South to the Deep South to meet ever growing demands for labor. Being a part of the interstate slave trade was a powerful incentive for enslavers. During the secession crisis of 1860-1861, commissioners from the nascent Confederate government reminded the Upper South that failing to join the Confederacy risked cutting off their access to this profitable market.6 The slave trade helped keep chattel slavery in the United States alive, and slaveholders and slave traders had a vested interest in its continuation, regardless of the difficulties posed by the war.

While the start of fighting created some disruptions in the trade, it soon rebounded and continued to the end of the Civil War. As Colby highlights, many in the Confederacy considered buying people to be a safe investment, especially when compared to the other options available. Confederate money was subject to hyperinflation, and land was immovable and could not be transported away from advancing Union regiments. The book is full of examples of people telling family members to buy enslaved people because they believed it would secure their financial future.

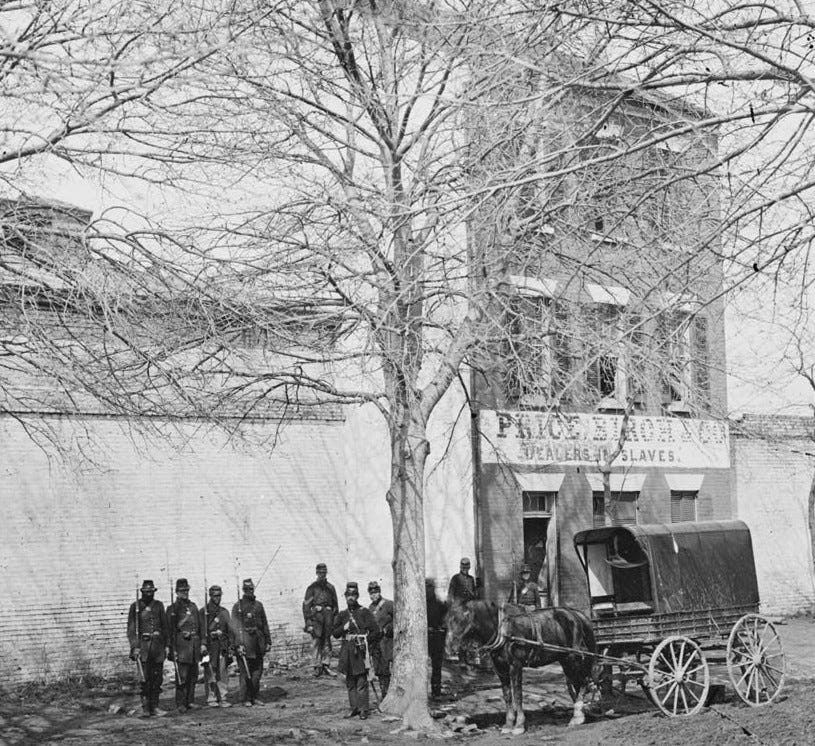

With many people eager to buy, slave traders proved to be highly flexible in responding to the challenges of wartime. Joseph Bruin, for example, moved his headquarters to Richmond once it became clear that the Union garrisons in Alexandria and New Orleans rendered his operations in those two cities unprofitable.7 Still, as Colby documents, there were limits to how much the traders could adapt, particularly once large numbers of soldiers in blue arrived.

“Thank God, that Yankees Come”

While organized slave trading thrived in areas controlled by the Confederacy, it rapidly imploded in areas controlled by the Union Army. Even before the Emancipation Proclamation (and even in areas like New Orleans that were exempt from President Lincoln’s order), the arrival of United States soldiers, as Colby notes “undercut municipal and state police powers, hindering the legal and extralegal mechanism that governed enslaved life and punished transgression against the white power structure…Federal invasion thus empowered enslaved people’s freedom-seeking and made slavery property so fundamentally risky a proposition that investment in it disappeared.”8 While not every Union soldier was supportive of emancipation (and some even attempted to make money by becoming kidnappers and slave traders themselves), the disruptions caused by Union occupation were enough to allow many enslaved people to challenge the structures that kept them in bondage and secure their freedom.

Selling While Richmond Burns

Reading the book, two separate stories emerge. One is of the buyers and sellers who kept the slave trade alive throughout the four years of war. The other is of the people trapped within the trade. The stories of the latter group include Black Union soldiers captured in battle and sent to an auction block rather than a POW camp, families torn apart when their enslavers needed money, and people sold away by their enslavers right before before the Union army arrived. Colby acknowledges that we have fewer records about the people caught up in the slave trade than we do about the people perpetuating it, but his research is able to illuminate the human suffering at the heart of the system. The book also highlights the efforts of Black Americans in the years after the war to undo some of the trade’s damage by reuniting with separated family members.

When it comes to the people perpetuating the slave trade, it’s hard not to scoff at their many pronouncements about what a good investment they’re making even as the Confederacy collapses around them. Still, it’s important to keep in mind that hindsight is 20/20 and both the outcome of the war and the fate of the institution of slavery hung in the balance for much of the conflict. While buying people in the later days of the war seems shortsighted to us (in addition to being morally repugnant), Confederates were analyzing the situation with the limited information they had. Colby does a good job of placing this all in context and laying out the motivations of the trade’s various participants. Still I’ll confess that reading about the enslavers who remained optimistic even in 1865 reminded me of The Simpsons episode where the out-of-touch Mr. Burns decides to review his antiquated stock portfolio and cheerily asks, “Confederated slaveholdings, how’s that doing?”

Documenting the Lingering Scars

In the aftermath of the Civil War, former Confederates set about rewriting history, doing everything in their power to present a narrative that the bloody conflict had nothing to do with slavery and that enslaved people were happy and content. An Unholy Traffic deals yet another blow to the Lost Cause narrative by shining a light on how vital the organized buying and selling of human beings was to the Confederacy. The book illuminates the deep scars left by the last few years of the slave trade and the the postwar efforts by freedmen and freedwomen to repair some of these wounds by trying to locate and reunite with the loved ones sold away from them. This is a text that both academic historian and casual readers will find valuable and approachable. Colby’s research is extensive and and his skill as a storyteller is on full display. Even as he takes the reader around the Civil War South, introducing new individuals and historic developments every few pages, he keeps the narrative accessible and engaging. I finished An Unholy Traffic with a better understanding of the Civil War, the Confederacy, and the slave trade, and with an appreciation for the copious research Colby did to make this book a reality.

A great addition to any Civil War bookshelf.

All views expressed in this article are my own and do not represent the views of any of my employers, past or present.

The Office of Historic Alexandria operates the Freedom House Museum, which interprets both the story of the slave trade and the history of Alexandria’s African American community. The museum is housed what remains of the complex.

Robert K.D. Colby, An Unholy Traffic: Slave Trading in the Civil War South, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2024), pg. 45-46.

Ted Pulliam, True Tales of Old Alexandria, (Charleston: The History Press, 2023), pg. 110.

Records indicate that it was mostly Union soldiers confined in that structure, although a few Confederates were imprisoned as well.

Obligatory disclaimer: Colby and I both worked for History Associates, Inc. However, our tenures never overlapped. I did meet him at a book talk once, and he seems like a nice guy.

Charles B. Dew, Apostles of Disunion: Southern Secession Commissioners and the Coming of the Civil War, (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2016) pg. 90-91.

Robert K.D. Colby, An Unholy Traffic: Slave Trading in the Civil War South, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2024), pg. 77.

Unholy Traffic, pg. 62.