Folks, just a heads up, today’s post includes unsettling images and descriptions of a Civil War prison camp. Reader discretion is advised.

“I dreamed of Eva last night, it was a sweet and pleasant dream,” Sergeant Jacob Osborn Coburn wrote on November 12, 1863. “I thought I made her a visit ‘in my suit of blue’ and that we were finally married before we came back.” Unfortunately for Coburn, reality soon intruded, “I awake and it was all a dream and I in this miserable camp.”1 Coburn was a prisoner of war, his fiancé Eva Aldrich was far away, and his dreams were only momentary escapes from the nightmare that was his daily life on Belle Isle.

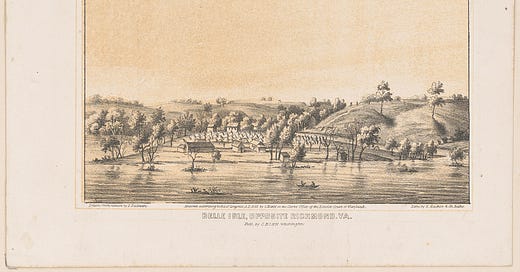

Located in the middle of the James River, before the Civil War Belle Island was a place for Richmonders to go, relax, and take in the area’s natural beauty. Research by Ranger Michael Gorman of the National Park Service indicates that the island also had businesses and several residents living there.2 After the war began and Richmond began to fill with captured United States soldiers, authorities determined that the picturesque island would be an ideal place to hold POWs. The James River provided water, yet also served as a deterrent against escape, and the island was close to the railroads that could bring in supplies or transport prisoners in and out. However, it wasn’t long before Belle Isle transformed into a place of misery, violence, and death. Confederate authorities couldn’t handle all of the prisoners arriving on the site. Not enough food and not enough shelter meant that the prisoners often went without food and protection from the elements. Some resorted to attacking and stealing from their fellow soldiers, further increasing the misery in the camp.

Coburn arrived in Richmond in November 1863 and spent the winter in the Belle Isle POW camp. Writing in his journal, Coburn described “From 3000 to 4000 lay out of doors with no protection from the cold, and those in tents have to lie upon the ground which is damp and cold.”3 Not surprisingly death rates were high. During the winter that Coburn was trapped there more than twelve soldiers died every single day.4

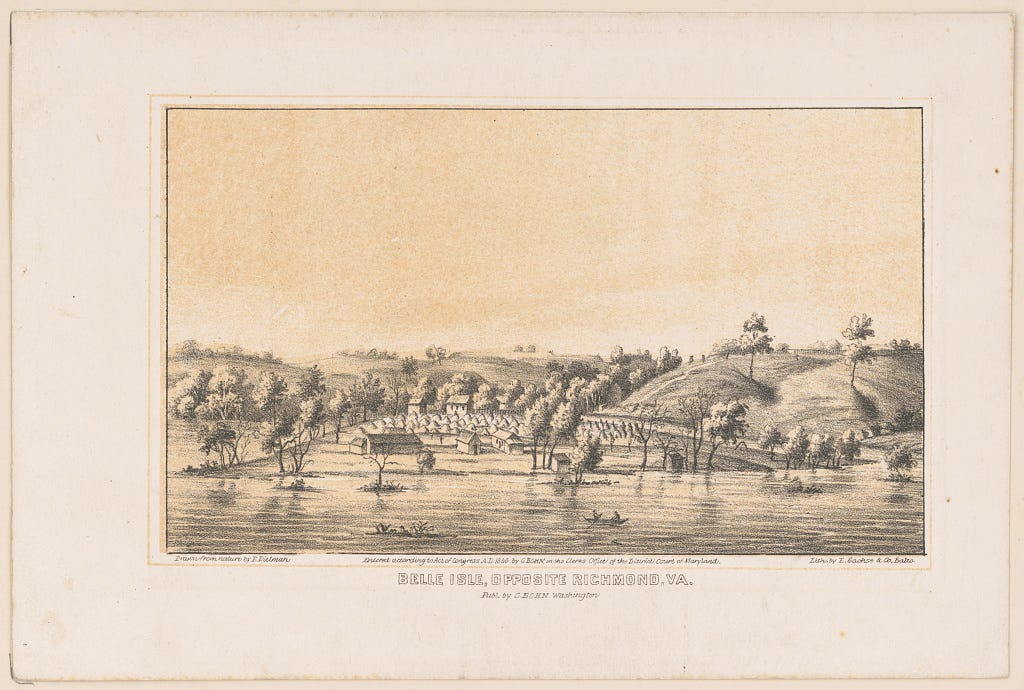

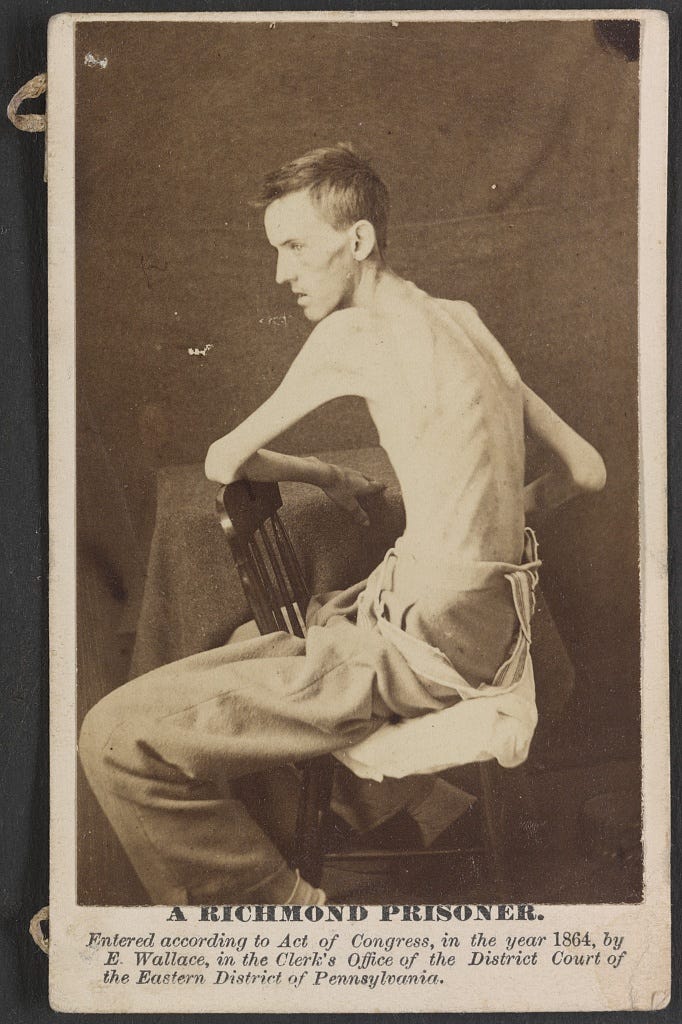

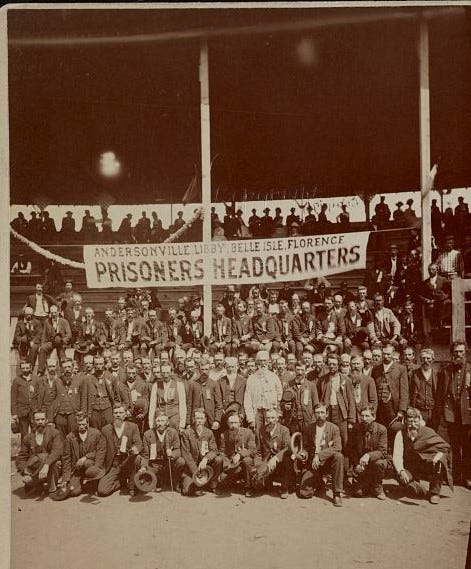

According to the National Park Service, around 1,000 POWS died during the time that Belle Isle was open out of a total of 20,000 US soldiers interned there between 1862 and 1864. The camp closed for good in the spring of 1864, although for most prisoners this was not the end of their ordeal. The Confederate authorities transferred many of them to Andersonville Prison in Georgia, where conditions were just as bad if not worse. There’s a good amount of debate about how much of the prisoners’ suffering was caused by Confederate authorities’ deliberate neglect and mistreatment versus how much was caused by the supply issues and lack of food that impacted the Confederacy’s war effort. I don’t have the space to cover the arguments of that debate here, but regardless of the cause, the prisoners on Belle Isle suffered through extremely harsh conditions, and it is not surprising that so many did not make it. Photographs of prisoners released from Belle Isle and other prison camps depict a harrowing picture of what they endured.

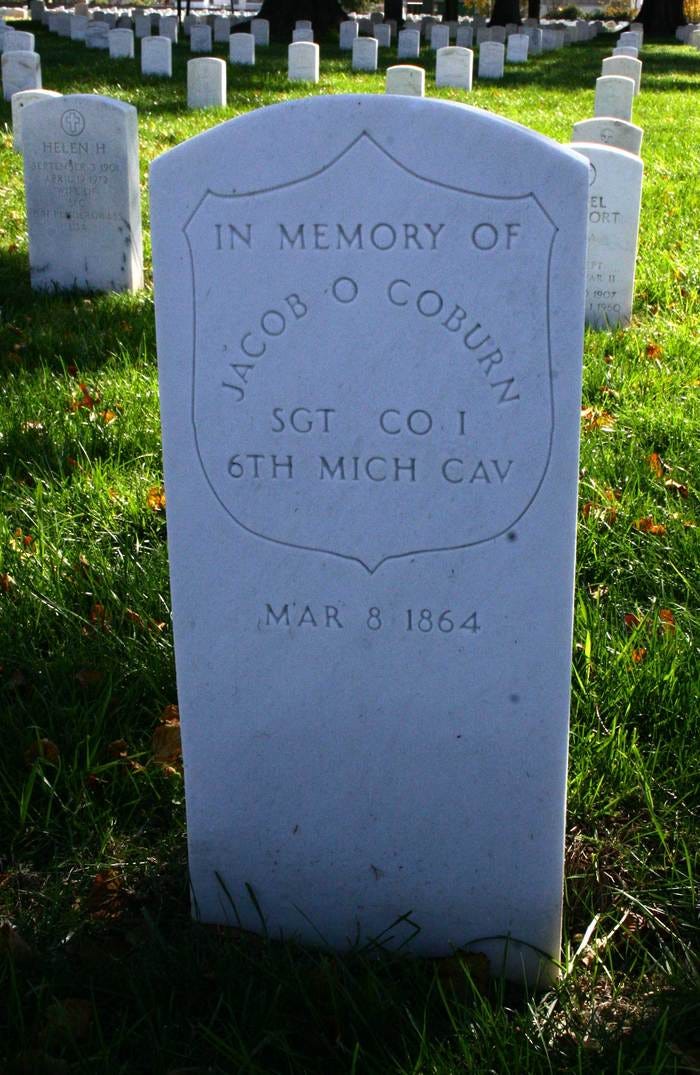

Sergeant Coburn never got the chance to go home and marry Eva Aldrich. Plagued by sickness throughout the winter, and growing weaker with each bout of disease, Confederate authorities eventually dispatched him to a hospital in February. By then it was too late, and he passed away on March 8, 1864. Today, his remains rest in Richmond National Cemetery. Hospital steward Albert S. Patrick took Osburn’s journal and returned it to his family, along with a letter to Coburn’s father that read, “Your son fell a victim to the inhuman cruelty and barbarous treatment of our captors and I do not overstate the truth when I say that he literally starved to death on Belle Isle.”5

“The Scene is a Golden One”

Over 150 years later, I stared across the James River. Snow was falling heavily, and I could just make out the outline of the island despite the low visibility. It wasn’t hard to picture Coburn and the other prisoners huddling together, attempting to stay warm. As much as I wanted to, I couldn’t go across the bridge to the island that day. The snow had made the trails impassable, and, since I was in Richmond for a work trip, I didn’t have the time to try and clear a way through the snow.

A few months after my first glimpse of Belle Isle, I returned to Richmond with a friend. After leaving the National Park Service Visitor Center and Museum at Tredegar Iron Works and the American Civil War Museum (both well worth a visit), we made our way to the island. Winter was long gone by now, and where once had only been a hazy outline, now there was a fully formed island covered in greenery and surrounded by the waters of the James. Walking across the bridge, it seemed that all of Richmond had turned out to enjoy the beautiful weather. We saw children carrying fishing rods, adults walking on the paths around the island, and everyone seemed to be having a good time. Laughter and smiles were everywhere. The history of Belle Isle wasn’t forgotten either. Waysides told the story of the prison camp, and a map of the island noted the former burial location for the soldiers. Still, the island itself seemed to have moved on. If the Belle Isle of Sergeant Coburn’s time was a place of death, the Belle Isle of the 21st century was a place of immense life and laughter.

Many Paths for Preservation and Interpretation

There is a belief that once a historically significant event happens, the space where said occurred is immediately preserved in amber. The opposite is often true (otherwise preservation organizations like the American Battlefield Trust would have very little work to do). For the unlucky farmers who had their farms turned into battlefields, repairing the damage and returning their fields to a state suitable for planting was an economic necessity. Historic houses often have multiple owners before they become dedicated tourist destinations. Even sites like Mount Vernon and Gettysburg have had extensive restoration work done to try and return them to how they might have looked during their periods of significance. However, for many sites comprehensive historic restoration is out of the question, whether due to budget constraints, land ownership rules, or local zoning realities.

After the prison closed for the final time in 1864 previous property holders reclaimed ownership of Belle Isle, and most of the evidence of the prison camp was destroyed or buried. The Virginia Power Company operated a power plant there for many years before the site became a park. Today, the Friends of the James River Park advertises the park as a place to bird watch, bike, hike, fish, picnic, climb, and enjoy scenic views in addition to learning about the island’s history.6

Historic preservation can be a tricky business. On the one hand, recreational activities can impact historic resources or be disrespectful. In other jobs I’ve held, I’ve had to tell multiple visitors to please be respectful of historic burial sites or to stop climbing on historic structures. At the same time, one needs to be mindful of the needs of the community and the history of a place after its main period of significance. Belle Isle has been a public park for decades. Attempting a full restoration of the park and prohibiting all recreational activities could lead to community blowback.

To be clear, this is not an either/or question. Most outdoor historic sites allow some recreational activities. At no point during my career have I ever said, “Birdwatching at a historic site!? Have you no shame?” The challenge is finding an appropriate balance. Most site stewards are probably fine with having someone jog on the trails of their site, but would understandably frown if said runner left the trails and ran on top of a cemetery or an archeological site.

Although Belle Isle is primarily marketed as a recreational park today, it’s still possible to have a meaningful experience engaging with the history. A visitor who has been exposed to the history of the site can understand how the beautiful waters of the James River can very quickly become walls if the bridge off of the island is closed off. They can see how cramped it would be if thousands of people had to live on the island at one time, and how quickly the beautiful foliage and abundant wildlife could disappear in the face of thousands of unhoused and hungry soldiers. All of this can happen without the restoration of the site or by banning other recreational activities.

Historical interpretation is about more than simply providing facts and giving visitors a chance to look at “something old.” Good interpretation catches the visitor’s attention, allowing them to make meaningful connections to the resource, and hopefully be excited to learn more. In this, I think the Belle Isle experience is profound. Would I have liked to see more interpretation there? Yes. However, the very fact that the island provides so many recreational opportunities that delight the community allowed me to reflect on how sites of pain and suffering can become places of joy, family, and community. The area’s beauty contrasted with its difficult history fostered a deeply moving experience.

The contrast of joy and suffering and beauty and pain are in a way reflected in Coburn’s writings. While he discusses the hardships he endured he also notes how he and his fellow soldiers worked to keep up their spirits and survive to the next day. Writing of the march to Richmond, he describes how, “Oh what a cheerless night, and yet the boys would sing Union songs, and sing them quite lustily, too.”7 Singing allowed the soldiers a distraction from the long marches, poor weather, and skimpy rations, while also giving them a chance to taunt their Confederate captors. While imprisoned in Richmond, but before being transferred to Belle Isle, Coburn looked over to the river and wrote:

“The sun is setting gloriously and from the windows of our prison room the scene is a golden one. The rippling water of the ancient James glistening beneath the soft mellow rays of the setting sun, the gold-tinted leaves of the Shintbery near and distant forest, the milky azure of the blue expanse above are all beautiful and so suggestive of the greatness and grandness of Nature’s works. One feels like seeing but to love them, but God’s works as all else is viewed to a better advantage where liberty and “a full stomach can assist in appreciating them.” 8

Standing in Belle Isle, with both a full stomach and personal liberty, a visitor who knows the story of the island can fully appreciate Coburn’s words and forge their own meanings as they reflect on the history around them.

Interpretation in the Present and for the Present

Every historic site is different and I’m not writing this post to say that rules and restoration don’t matter. Many sites have benefited immensely from engaging in restoration or reconstruction work, and sometimes recreational activities do need to be curtailed in the name of preservation, visitor safety, or respect for sacred sites. This post should not be taken to mean that preservation activities do not matter, they absolutely do. Historic sites that focus heavily on restoration work or those that prohibit recreational activities don’t necessarily need to change things up, provided that they are forging meaningful connections between the site’s history and their visitors.

For those sites that have experienced significant physical alterations to their landscapes over the years or are viewed primarily as recreational areas by their communities, there is no need to despair. What Belle Isle shows is that history, even difficult history, can coexist and even be enhanced by natural beauty and recreational activities. Site managers should ask themselves, how are we engaging the public with this history, what opportunities are we providing visitors with to learn about this history, and what meanings can be drawn from both the past and present of our site?

I’m not sure what Sergeant Coburn would think about Belle Isle today. His writings don’t discuss historic preservation and interpretation, naturally, he was focused on surviving and getting home to his fiancé. The same is true for most people we talk about in history. While in some instances people who lived through historic events are able to provide their perspective on what the historical interpretation should look like, in many cases we don’t know how a person wishes to be remembered. Would Coburn be annoyed that the Belle Isle isn’t fully restored to what he saw in 1863? Would he want his story to be told at all? Would he see the families with children coming to Belle Isle, something he never got to have with Eva Aldrich, as a powerful lesson on how life and joy continue despite all the death and pain in the human story? I don’t know, and I’ll never know. If I was in charge of Belle Isle (which to be clear aside from working on an app many years ago where Belle Isle was one of the stops, I have no formal relationship with the island or its management), all I can do is make sure I’m telling the story in a way that resonates and connects with visitors.

What I do know is that while historic sites tell the story of the past, but they are just as much about the present. A place for the living as well as a space to remember the dead. In that sense, the question becomes less about what a person in the past would think, and more about how we are getting visitors (both physical and digital) to connect with these stories. It can be very moving to walk through a space that looks close to what it did 150 years ago, just as it can be very moving to stand in a space designed for silence and contemplation, and, yes, it can be very moving to be in a space where life, laughter, and happiness coexist with a history that was anything but.

J. Osburn Coburn, Hell on Belle Isle: Diary of a Civil War POW, Don Allison (ed.), (Bryan: Faded Banner Publications, 1997), 86.

Mike Gorman, “Belle Isle Prison, Civil War Richmond, http://www.mdgorman.com/Prisons/belle_isle_prison.htm

Coburn, Hell on Belle Isle, pg. 85

“Prisoners In Richmond,” National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/rich/learn/historyculture/prisoners-in-richmond.htm

Coburn, Hell on Belle Isle, pg. 144

“Explore the Park: Belle Isle,” Friends of James River Park, https://jamesriverpark.org/explore-the-park-belle-isle/

Coburn, Hell on Belle Isle, pg. 42

Coburn, Hell on Belle Isle, pg. 50