How is a historic site saved?

Creating and sustaining the battlefields, historical parks, cemeteries and historic house museums we know today

On January 3, 1777, the Continental Army defeated a British force at the Battle of Princeton. As his troops chased after the redcoats, General George Washington surveyed the battlefield. “Future generations should know what happened here,” he thought to himself.

“General, they’re here,” an aide shouted. Right on cue, three employees of the Continental Congress Taskforce for the Preservation of Historic Sites arrived on the scene. It was their job to survey and document the battlefield. Once that was complete, they would pay the local property owners an above-market price for the land. The government would preserve the battlefield precisely as it looked in 1777 for future generations to visit and learn about the past.

“Bless you, gentleman,” George Washington said as he grasped each one by the hand, “I cannot wait to see the visitor center once it’s open.” From that moment on, the Princeton Battlefield was preserved and never faced any threats or challenges. There was just one problem…

That’s not remotely what happened.

Millions of people visit the United States’s many historic sites each year. Ranging from small houses to massive battlefields, these places are run by a variety of organizations, from tiny nonprofits with shoestring budgets to large federal agencies like the National Park Service. Having worked at a couple of these sites myself, I want to dive into the often long and windy road that transforms a historically significant site from private property to public asset. For our purposes, we’ll just be looking at historically significant sites that are preserved with the goal of making them available to the public. There are many historic buildings that are preserved but remain private residences or businesses, but that’s a topic for another post.

Lost like tears in rain

There’s no guarantee that a place with historical value will be preserved for future generations. Benjamin Franklin’s old house in Philadelphia was torn down, as was the cabin where Abraham Lincoln was born and the house where George Washington grew up. Many sections of key battlefields have been built over. At Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park, the approach to Marye’s Heights, where thousands of US soldiers died attempting to take the Confederate position, is now covered in houses, businesses, and streets. As a ranger there once told me, “The city of Fredericksburg has gotten closer to the Confederate position on Marye’s Heights than the Union Army did.” This loss of historical resources isn’t limited to the United States; for years, the Colosseum in Rome was used as a source of building materials, and the Circus Maximus racetrack was abandoned and partially dismantled.

There’s no switch that automatically flips when a site acquires historical significance. A building might be historic, but for many people, it remains, first and foremost, a building. When someone sells their home or business, the new owner typically isn’t looking to turn it into a museum, even if they are aware of its significance; they want a place to live/work/make money.

In some instances, the importance of a place cannot be grasped until many years after the most significant part of a site’s history (also known as the period of significance). The Lincoln family left his birthplace in 1816, so there’s no way that the subsequent owners could possibly have known they’d just bought the former home of the future 16th president of the United States. It would be another 44 years before his election.

For anyone unfortunate enough to have their home become a battlefield, the main goal after the fighting stops is typically not preservation but rebuilding. Going back to the Battle of Princeton, much of the fighting occurred on land owned by the Clarke family. Not only did their farm become a battlefield, but in the weeks leading up to the battle, both British and Patriot forces had foraged through the area and taken food, livestock, and wood. After enduring all of that, it’s only natural that most of their efforts in the days after the armies departed would have focused on fixing the damaged buildings and fences and replenishing food stores taken by the soldiers. Their priority was making it through the winter, not preserving the area for posterity.

There are some places where active historic preservation takes place during or right the period of significance).1 After Theodore Roosevelt’s death, his widow, Edith Roosevelt, worked to ensure that their home in Sagamore Hill was preserved and made plans for the transfer of the site to a nonprofit after her death.2 Still, stories like these are the exceptions.

Preserving a place

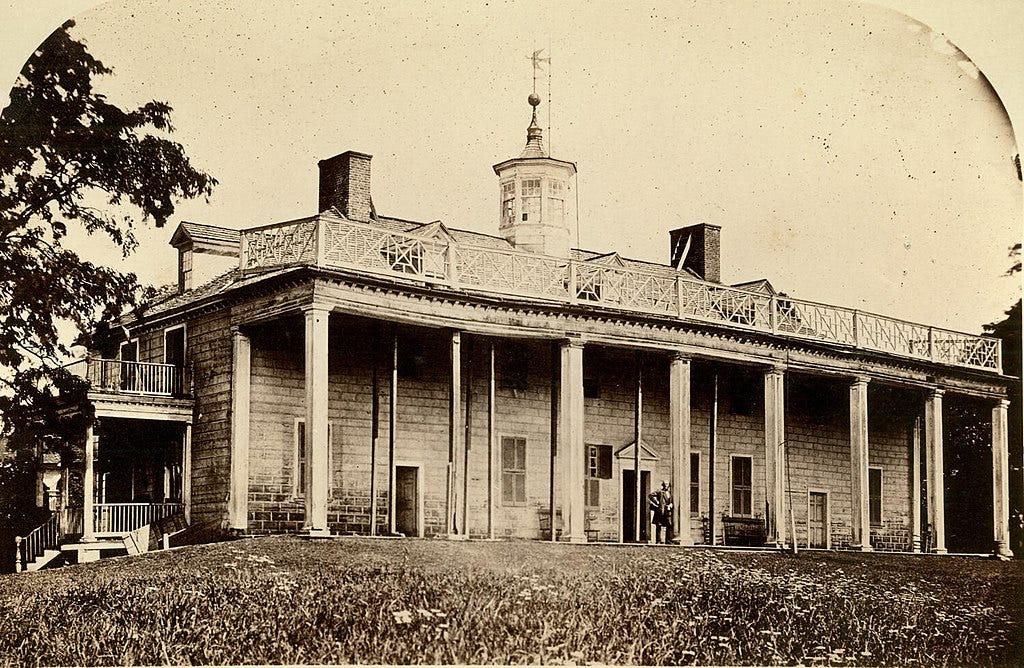

Historians generally date the start of the historic preservation movement in the United States to the nineteenth century, with the Mount Vernon Ladies Association (MVLA) being one of the earliest documented preservation organizations.3 Founded by Ann Pamela Cunningham, the group embarked on a nationwide fundraising effort in the 1850s to purchase George Washington’s former home from its last private owner. Their efforts foreshadowed the work of many later preservation organizations. The group was a nonprofit organization comprised of concerned citizens who fundraised extensively to purchase a historically significant property from a private owner. After the purchase was completed, the MVLA took over the management of Mount Vernon and continue to own and operate it today as a historic site.

Preservation activities began to gain additional steam in the second half of the 19th century. In the aftermath of the Civil War, veterans organizations and their allies worked to commemorate and protect some of the lands where their fellow soldiers had fought and died.4 Due to their advocacy, Congress passed laws to preserve and administer some of these battlefield lands and gave oversight to the War Department (management duties were later transferred to the National Park Service in the 1930s).5 Meanwhile, new preservation groups, often taking inspiration from the MVLA, worked to preserve other historic homes.

In the 20th century, the preservation movement’s progress accelerated. The 1906 Antiquities Act gave the president the authority to protect cultural heritage sites on federal land.6 State and national organizations, like the National Trust for Historic Preservation and Preservation Maryland, were formed to purchase and preserve historic sites. Colonial Williamsburg opened in the 1930s and became the premier living history site in the country, with its original and reconstructed buildings drawing visitors from around the world.7 State and local governments increasingly became involved in purchasing and operating historic lands and buildings. The National Historic Preservation Act of 1966 (NHPA) mandated the creation of state historic preservation offices (SHPOs), established the National Register of Historic Places, laid out a process for assessing if federally-funded projects would negatively impact historic sites, and made federal funds available for historic preservation efforts.8 The portfolio of historic places managed by the National Park Service grew. The 1976 Bicentennial of the United States prompted another wave of preservation efforts.

Many of the homes and structures originally targeted by preservationists were those of the wealthy and powerful. In more recent decades, preservationists and advocates have increasingly worked to ensure that the country’s historic sites reflect a broader portion of the country’s history. Places like the Tenement Museum in New York City preserve the former homes of some of the many immigrants who came to the United States searching for a better life. The Stonewall National Monument preserves the site of a key event in the struggle for LGBTQ+ rights. Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historical Park and the Medgar and Myrlie Evers Home National Monument preserve the homes of leaders in the Civil Rights Movement. Nonprofit, state, and federal programs like Virginia’s African American Cemetery & Graves Fund provide funding to support local efforts to protect historically significant but often overlooked places.

In recent decades, there has been a greater focus on preserving and restoring the surrounding landscapes of historic buildings. This extended focus includes associated structures like sheds, privies, and barns and features like gardens, fences, and natural vegetation.9 In some instances, site administrators will work with nearby landowners to place conservation easements on adjacent lands to preserve historic viewsheds.10

Compared with the 1850s, when Ann Pamela Cunningham began organizing to save George Washington’s house, the preservation landscape looks very different today. The National Park Service manages historic sites throughout the country. National organizations like the American Battlefield Trust and the National Trust for Historic Preservation lead preservation efforts and provide funding, advocacy, and expertise to smaller organizations. In contrast to the early preservationists, who often had to make up best practices as they went along, today, there are universities that offer degrees in historic preservation, and professional organizations like the National Preservation Institute offer classes and webinars for transmitting preservation knowledge and skills.

Still, the similarities between the early years of the preservation movement and its more recent history remain striking. No matter the decade, the process of preserving a place starts with someone thinking that it should be. That person, whether a private individual or a member of a larger organization, begins to gather allies who agree with them. They then either start fundraising to purchase it themselves or lobby policymakers to acquire the site. If the site is on public land, the group will lobby the government (local, state, or federal) to place the appropriate protections on the site. Sometimes, the group makes a powerful political ally early in the process (or is led by a political figure from the beginning) who helps speed the preservation project to success, but other times, it involves years or decades of effort and struggle. Skills like marketing, public outreach, fundraising, lobbying, budgeting, and project management are all required for a successful preservation effort.

Eventually, if all goes well, the people advocating for the preservation of a site declare victory. Either a government agency has acquired the site, appropriate designations have been put in place, or a nonprofit has purchased the site outright. When that happens, everyone celebrates. But that’s not the end of the story.

Writing a historic site’s next chapter

A key question facing preservationists during the effort to save a place is who will own and operate the site once it is saved. Sometimes, the organization that led the fight to save the site takes on operational responsibilities. In other cases, the site is transferred to another organization, like the National Park Service. Sometimes, a nonprofit later finds that it is unable to properly maintain a site, and a government entity steps in to take over operations (the reverse can also happen when a nonprofit partner of a government-run site takes on additional responsibilities if public funding is slashed). In a few instances, including the Potts-Fitzhugh House in Alexandria, Virginia, site administrators reach a point where they are unable to secure enough funding and support, and the site permanently closes.11

For a historic site to stay afloat, proper planning is crucial. Preserving and interpreting a site after it has been acquired requires the skills of many different people, including historians, cultural resource specialists, preservation architects and landscape architects, strategic planners, economic planners, interpretive planners, and property management specialists, to name a few. It is time-consuming and labor-intensive work.

Managing historic sites is challenging. Maintenance needs are likely to increase as time goes on, and site administrators need to balance preservation with facilitating public engagement and access. Finances are a significant issue for many sites. Since admission fees are rarely (if ever) sufficient to cover all costs, most historic sites rely on a combination of fees, proceeds from gift shops, donations, grants, and endowment funds to stay afloat.

Sites also need to determine what type of work they’ll perform on the structures and landscapes in their care. Since most places have private owners after their period of significance, alterations and changes that postdate the time period of interest are common. The Department of the Interior defines four major types of treatments for historic structures: Preservation (maintaining the structure as is with limited alterations), Rehabilitation (making changes to the structure to facilitate a new use- such as turning an old barn into a visitor center), Restoration (working to return a structure to its appearance during the time period of significance), and Reconstruction (attempting to recreate from scratch a building or landscape that is no longer there).12 Decisions on which treatment to pursue depend on an organization’s budget, available documentation on the original structure, and the needs and goals of its administrators and stakeholders. At Mount Vernon, several generations of owners after George and Martha Washington made additions and alterations to the mansion building. After assuming ownership, The MVLA eventually decided to pursue a policy of restoration for the mansion itself, removing parts of the building that post-dated George Washington’s death in 1799. Around the estate, they’ve also pursued several reconstruction projects to rebuild old structures that were no longer standing, including the Slave Barracks/Greenhouse and Blacksmith Shop.

Site administrators also need to determine how they will connect a site’s story to the public. A place's history is not self-evident. If visitors don’t have the tools to understand its past, then the site, no matter how significant, risks becoming just another old building or grassy field in the public consciousness.

Historical interpretation is the meaningful communication of a site’s history and relevance to the public. Site administrators need to determine what stories from which time periods they want to prioritize and what tools (guided tours, signage, apps, social media, etc.) make the most sense to connect said stories to the public, a process known as interpretive planning. Interpretation is critical to the success of any historic site since it fosters a connection between a place and a visitor and helps create future supporters and donors. It answers the questions of “Why is this place worth saving?'“ and “Why should I care?” ensuring that these sites stay relevant to local communities and the broader public.

Properly interpreting a site also means understanding its history. Just because a site has been preserved doesn’t mean its entire past is immediately understood. Often, an organization needs to hire historians, archeologists, cultural landscape experts, and other specialists to get a better sense of a site’s historical significance and context. Conversations with local stakeholders, descendants, and community members often also need to occur as well. Exploring a site’s history is an ongoing process and site administrators, staff, and volunteers often need to revisit their previous understanding of a place’s past based on new information.

For larger sites, like historic towns or battlefields, acquiring additional land or structures often remains an ongoing process even after the site opens to the public. Princeton Battlefield State Park opened in 1946, but not all of the battlefield was included in the park boundaries. The land where George Washington rallied the Continental forces and led a successful counterattack remained in private hands. When the private owner planned to develop this land, it sparked a massive preservation effort that culminated in the American Battlefield Trust buying the land and beginning the process of adding it to the state park.13 Even Gettysburg National Military Park, where preservation efforts started not long after the battle was fought, has battlefield land outside of the park boundaries not (yet) protected.14 Organizations like the American Battlefield Trust work to identify tracts of land and ensure they’re added to previously protected landscapes.

Preserving the past for the present and for the future

Preserving a historic site doesn’t happen by magic, and keeping a preserved site open to the public isn’t a given. Both require detailed planning and management. There’s also no silver bullet for success, and what works for one place might not work for another. Each historic site in existence today represents the cumulative efforts of many different stakeholders and advocates. Ultimately, while having a vision helps get the preservation process started, it is a confluence of practical skills and the hard work of many people that ensures that a site will remain protected and open to the public for generations to come.

“National Historic Landmarks: Glossary of Terms,” The National Park Service, last updated August 29, 2018, https://www.nps.gov/subjects/nationalhistoriclandmarks/glossary.htm

H.W. Brands, Kathleen Dalton, Lewis L. Gould, Natalie A. Naylor, Theodore Roosevelt and His Sagamore Hill Home: Historic Resource Study, (National Park Service, 2007), pg. 134.

John Sprinkle Jr., Saving Spaces: Historical Land Conservation in the United States, (New York: Routledge, 2019), pg. 2. To be sure, people had preserved sites for their religious or sacred reasons in the past, so, to the best of my understanding, the 19th century was when sites of secular significance began to be targeted for preservation.

“A Short History of the Battlefield Preservation Movement,” American Battlefield Trust, accessed on June 9, 2024, https://www.battlefields.org/about/history/short-history-battlefield-preservation-movement#:~:text=Civil%20War%20veterans%20began%20erecting,auspices%20of%20the%20War%20Department.

Harlan D. Unrau, Gettysburg National Military Park and National Cemetery: Administrative History, (Gettysburg; National Park Service, 1991), pg. v-viii.

“Antiquities Act of 1906,” The National Park Service, last updated March 30, 2023, https://www.nps.gov/subjects/archeology/antiquities-act.htm

Anders Greenspan, "Colonial Williamsburg" Encyclopedia Virginia, December 7, 2020, https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/colonial-williamsburg/

“National Historic Preservation Act,” The National Park Service, last updated November 1, 2023, https://www.nps.gov/subjects/historicpreservation/national-historic-preservation-act.htm (Note: the act was later amended to establish tribal government historic preservation offices (THPOs) as well.

Charles A. Birnbaum, 36 Preservation Briefs: Protecting Cultural Landscapes: Planning, Treatment, and Management of Historic Landscapes, (Washington DC: National Park Service, 1994).

“Easements,” George Washington’s Mount Vernon, last visited July 14, 2024, https://www.mountvernon.org/preservation/viewshed/easements

“Robert E. Lee’s Childhood Home is Sold,” The New York Times, March 12, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2000/03/12/us/robert-e-lee-s-childhood-home-is-sold.html

Kay D. Weeks and Anne E. Grimmer, The Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for The Treatment of Historic Properties with Guidelines for Preserving Rehabilitating, Restoring, and Reconstructing Historic Buildings,(Washington DC: National Park Service, 2017) https://www.nps.gov/orgs/1739/upload/treatment-guidelines-2017-part1-preservation-rehabilitation.pdf, PDF pg. 12-13.

“Washington’s Legacy: Transform the Princeton Battlefield, Honor Revolutionary Heroes,” The American Battlefield Trust, https://www.battlefields.org/preserve/washingtons-legacy

“Breaking News: American Battlefield Trust to Preserve Critical Part of Gettysburg’s First Day Battlefield,” Emerging Civil War, October 5, 2023, https://emergingcivilwar.com/2023/10/05/breaking-news-american-battlefield-trust-to-preserve-critical-part-of-gettysburgs-first-day-battlefield/