An extra-Ward-inary city

The contentious history of city council elections in Alexandria, Virginia

Located just a few miles south of Washington, D.C., the City of Alexandria has a complex and compelling history. General Edward Braddock launched his ill-fated expedition here during the French and Indian War, a Union garrison was based here during the Civil War, and activist Samuel Tucker organized one of the documented sit-in protests of the Civil Rights era here in 1939.

Given Alexandria’s long history, it is only natural that current policy debates often involve discussions of the city’s past. A while back I got the chance to participate in a panel focused on the history of elections in Alexandria and what reforms are needed regarding how we vote, who we vote for, and when we vote. One of the topics discussed was ward elections vs. at-large elections for city council. In an at-large system, voters vote for a slate of city council members, so if the city council has 7 seats, I would vote for seven people out of all the nominees on the ballot. By contrast, in a ward system, a locality is divided into several districts (i.e. wards) with residents of each ward electing their own representatives. Alexandria currently has an at-large system for city council elections (and a ward system for school board elections, but that’s a topic for another day).

While the panel covered many other topics relating to elections, the question of whether the city should return to a ward system of electing city council has recently come up in community conversations again. In fact, one of the questions asked by The Washington Post in a recent profile of the candidates for mayor and city council was whether the candidates favored a ward system or an at-large system. Along with this discussion has also come some misinformation and some arguments that could use a little more historical context.

We a-ward you a new system of government

When Alexandria was founded in 1749, the Virginia House of Burgesses appointed a board of trustees to govern the new town. How did one become a trustee? Either be a part of the initial group appointed by the Burgesses, or be asked to join by the current trustees. There were no elections or term limits for trustees, and they stayed in office until they either resigned or died.

Alexandria historian T. Michael Miller accurately described this as an oligarchic system, and, unsurprisingly, it didn’t last forever.1 During the American Revolution, the Virginia legislature formally incorporated the town and allowed it to switch governments. An elected city council replaced the board of trustees.2 Council members selected a recorder, a mayor, and several aldermen from their ranks. Who could vote, however, was still limited. State law restricted the franchise to white men who met certain property requirements.

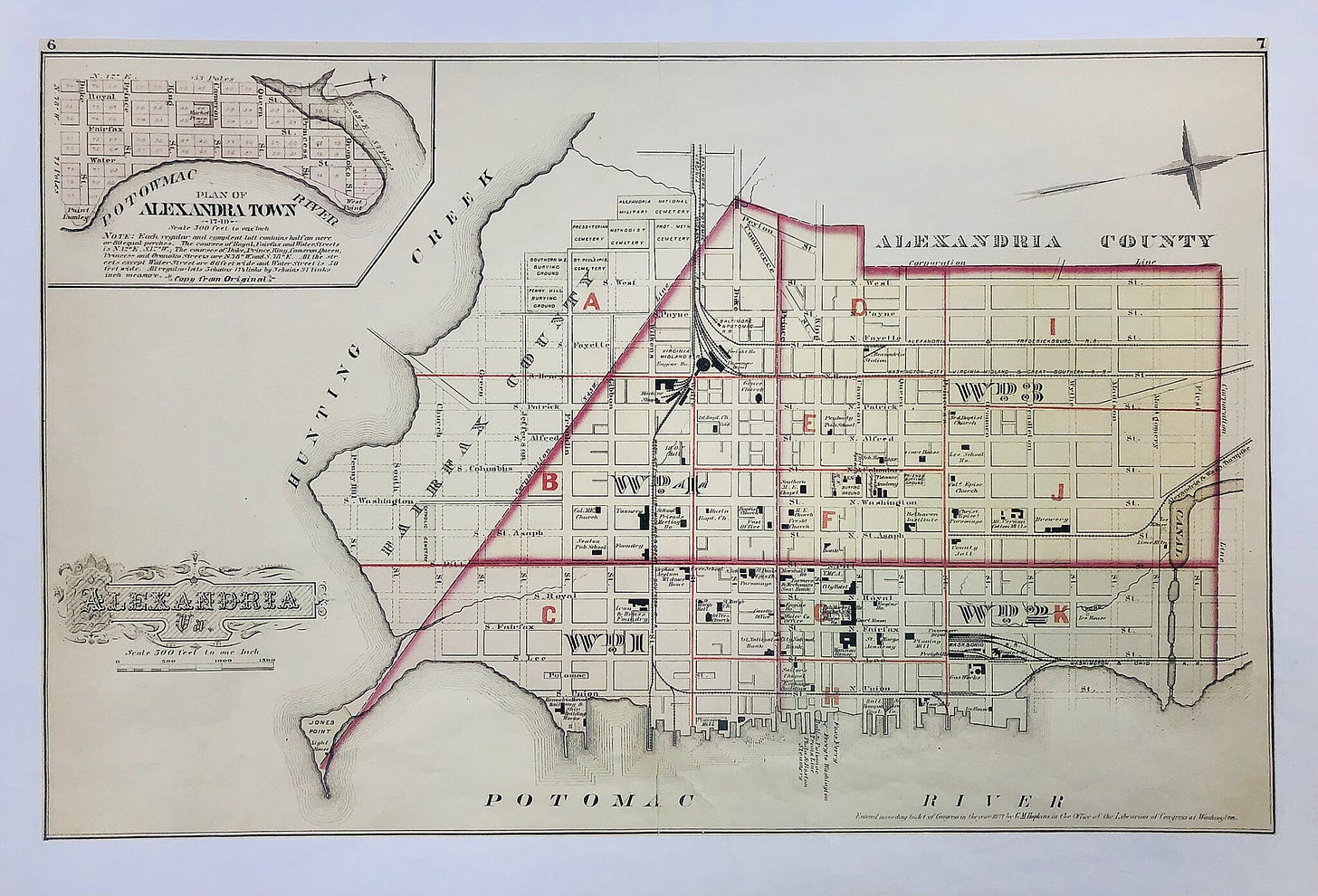

This early city government was elected through an "at-large” system of elections, but after being transferred to the new District of Columbia, the US Congress gave Alexandria a new charter in 1804, which mandated a ward system. The city was divided into four wards, with each ward electing four council members.3 In 1852, a few years after the city was retroceded back to Virginia, the Virginia legislature gave it a new charter that retained the ward system and brought back the board of aldermen to govern the city alongside a mayor and city council.4

In 1921, Alexandria moved to a city manager form of government, a system in which the day-to-day administration is overseen by a hired professional.5 The elected governing body was reduced to a five-member council elected at-large, with the mayor selected by the council.

This system lasted for around a decade until 1932, when a new city charter brought back the ward system in modified form. The city was divided into six wards, with each ward electing a member of the city council. There were also three other council members who were elected at-large. Alexandrians elected city council members this way until 1948 when, following a referendum, the law was updated to make all council elections at large [note: some sources have the switch occurring in 1950 when the charter was updated, but it was in 1948 when the referendum and the first elections under the new at-large system were held]. In the 1950s, the city’s charter was updated to allow direct election of the mayor.

Not enough to Ward off debate

Just because the city’s current method of electing the mayor and city council has been in place for almost 75 years doesn’t mean it no longer inspires controversy. In fact, debates about ward vs. at-large systems of elections seem to come up every few years, and while they have yet to inspire an actual change to the voting system, it is possible that one of these efforts might succeed in the future.

For that reason, it is important to get the historical facts straight. If history is to inform the creation of good public policy, then said historical analysis needs to be built upon well-researched and accurate information. Right now, two points being made in the ward debate deserve either correction or further reflection: how long the city historically had a ward system and whether it was abolished as a tactic to maintain white supremacy.

Wards and all

The first point is easy to debunk. As noted earlier, the city had an at-large system for most of the 1920s, and we have old government documents and newspaper accounts supporting this fact. While it’s accurate to say that the city had a ward system for most of its history, it is not true to say that it had one for an uninterrupted 150 years. The ward system itself also changed over time, including an era when at-large representatives were elected alongside ward representatives and a time when each ward elected four representatives instead of one.

Why the confusion? It might come down to the fact that Alexandria continued to use wards as administrative areas, so someone reviewing documents from the time would still see the term mentioned, even though voters of different wards were all voting on the same slate of candidates.

The second question of what motivated the switch back to an at-large system in 1948 is more complicated. A 2021 article in Alexandria Living Magazine states that “A large part of the reason Alexandria moved to an at-large system in 1950 was to intentionally limit minority voices. The move, after nearly 150 years of ward representation, was part of widespread resistance to school desegregation to ensure fewer voices from minority neighborhoods.”6 However, the article doesn’t provide any sources or evidence for this.

The critique that an at-large system disempowers minority groups is neither new nor limited to Alexandria. In 1969, Preston M. Yancy writing in The Baltimore Afro-American noted that in Richmond, Virginia, “When it became impossible to gerrymander the city a switch was made to an at-large method of electing City Council.”7 There have been a number of successful court cases where judges have ruled that at-large systems disadvantage minority voters. A few years ago, a court declared that the City of Virginia Beach had disempowered minority residents by using an at-large system rather than a ward system.8

Yancy’s argument about Richmond noted that the city was reacting to the demographic growth of the city’s Black population by switching from wards to an at-large system. Was something similar happening in Alexandria that prompted pro-at-large campaigners to advocate for the change in representation? In 1940, the census listed Alexandria as having 5,281 Black residents, representing about 15.8% percent of the population.9 In 1950, the census listed Alexandria as having around 7,622 Black residents, but due to growth in the city’s white population (which had nearly doubled during this decade), their percentage of the total was only 12%.10 The “Economic Summary of Alexandria, Virginia, a report from 1947 found in the papers of Alexandria politician Armistead Boothe, declares, “the colored population has grown very little since 1940.”11 The city’s Black population was scattered between the various wards, and it seems unlikely that all of the population growth occurred in only one section of the city. While at-large campaigners may have been motivated by a “perceived” growth in Alexandria’s Black population, the fact that all official data showed the opposite suggests that the question deserves further review.

The 1948 referendum owed much to the efforts of Delegate Armistead Boothe. Boothe speared the effort to have the General Assembly bGeneral Assembly authorize a referendum, something that apparently took the Alexandria City Council by surprise.12 Why did Boothe move so quickly to get the referendum on the docket? Was he concerned enough about preventing Black Alexandrians from voting that he felt the need for a referendum as soon as possible?

When it comes to civil rights, Boothe’s record is mixed. As city attorney, he vigorously prosecuted the activists involved in the 1939 Alexandria Library sit-in demonstration. As one historian put it, Boothe:

“personified tradition, continuity, and the status quo. As city attorney and vice president of the library board, he vigorously prosecuted the demonstrators and forcefully represented the interests of city and library officials. His exuberance led him to present questionable arguments rejecting the Fourteenth and Fifteenth amendments.”13

However, Boothe was also a thorn in the side of the powerful, pro-segregationist Byrd Political Machine that governed Virginia during this era.14 Boothe supported poll tax repeal, and tried to pass a law that desegregated the state’s transportation system, even though many white Alexandrians opposed him.15 In 1950, Boothe received a commendation from the Third District of the Omega Psi Phi Fraternity, a historically African American fraternity, for his civil rights legislation.16 To be sure, Boothe was no radical. In the legislature, he promoted a gradual move away from segregation and, as the sit-in case demonstrates, was not opposed to standing against civil rights activists. Still, it is doubtful that he was so concerned about limiting Black voting rights in 1948 that he would go behind the city council’s backs. After all, the city council at the time (which ended up being divided on the at-large vs. ward question) was hardly a bastion of racial progressivism.

Ultimately, the documents I reviewed did not include any overt or coded language suggesting that racism was the primary motivator of Alexandria’s shift to the at-large system in the 1940s. Instead, the arguments focused on how wards were based on “‘drawing an imaginary line around a few city blocks,’ and preventing those residents from voting for councilmen from other parts of the city.”17 The wards could be an administrative headache. In 1944, Virginia’s attorney general rebuked Alexandria for not updating the boundaries to account for the city’s shifting and growing population, noting that Ward Two had 992 voters while Ward Six had 3347 voters.18 The ward system could also be uncompetitive, as councilmembers for office in several wards sometimes ran for reelection unopposed.

The city held two referendums on the ward question. In 1944, the majority of voters supported the ward system, while in 1948, they opposed it. Both referendums occurred during the era of Jim Crow segregation and disenfranchisement, so the vast majority of Alexandria voters would have been white. In the space of those four years, were the voters suddenly convinced that wards represented a threat to white supremacy? Possibly, but local anger about scandals and mismanagement seems more likely. Evidence suggests financial mismanagement and higher taxes in the 1940s appear to have hurt the system’s credibility.19 The selection of Nicholas A. Colasanto as city manager, whom critics viewed as unqualified, was used by one business group to advocate for moving to an at-large system and was later cited by a reporter as being the spark that started the campaign to do away with wards in the city.20

In the 1948 referendum, the at-large system won a majority of voters in five out of the six city wards. In the Sixth Ward, voters overwhelmingly opposed it. Was this because this ward was a bastion of equal rights in a Jim Crow city? Quite the opposite.

The Ward on the street is…

The argument has been made that it was the move to the ward system in the 1930s, rather than the move away from it in 1948, that was driven by a desire to limit Black political power. In 1930, Alexandria annexed a section of Arlington County which included the Town of Potomac. In a 1924 publication, the town boasted that it was “perhaps the only municipality in the United States in which ownership of real estate is limited to persons of the Caucasian race, and it is also the only municipality so far as known, that does not number among its residents persons of African descent.”21 Many residents of the Town of Potomac fiercely resisted being annexed by the City of Alexandria. While Alexandria itself was also deeply enmeshed in Jim Crow racism, it did have a sizable Black community, so it is possible that racial resentment in Potomac motivated both the fight against annexation and the effort to move to a ward system.

However, it is also possible that neither the move to the ward system in 1932 nor the move away from it in 1948 was primarily motivated by racism. In 1932, while Alexandria was more diverse than the Town of Potomac, the poll tax and other voting restrictions locked the city’s Black community out of power, so it’s not as though Potomac residents had to worry about being governed by a racially diverse council (Alexandria’s first post-Reconstruction Black member of the city council wasn’t elected until 1970). The Town of Potomac had feuded with Alexandria over municipal issues even before the annexation controversy, so it is possible this influenced their desire for a dedicated representative on the city council. Residents of Potomac also cited the fact that none of the members of the city council lived in their community as a primary motivator in their fight for ward representation. Opponents of the ward system in the 1930s included the Alexandria city council and the chamber of commerce, hardly beacons of integration and voting rights for all.22 Could racism have been the primary driver for Potomac residents’ desire for a ward system? Possibly, but the desire for more representation in a governing body that had annexed them against their will seems like the more plausible reason.

Moving forWard (with or without wards)

Despite being locked out of elected office, Alexandria’s Black community fought back against the racist rules of Jim Crow. Activists protested and initiated lawsuits to integrate schools and libraries, repeal the poll tax, and push back against urban renewal projects that disproportionally impacted their communities. As the Civil Rights Movement notched victories at the national level, changemakers in Alexandria continued to combat Jim Crow and its legacy. However, returning to a ward system did not appear to be high on their list of priorities, even when their allies at the state and national level were advocating for it.

In the 1980s, the Virginia chapter of the NAACP embarked on an ambitious plan to improve representation on city councils and county commissions around the state by urging a switch from an at-large to a ward system for electing local officials. Over the next few years, they and the ACLU would initiate a series of court cases that would compel many municipalities to adopt ward systems. However, even though Alexandria was on their list of localities, the reception from the local NAACP branch was mixed. President of the Alexandria NAACP Ulysses Calhoun, when asked for his thoughts on the proposal, tepidly offered that it “might help here” before stating, “I really don’t know why Alexandria was picked.”23 Lionel Hope, who at the time was the only Black representative on city council, echoed Calhoun, “in a city like Alexandria a ward system wouldn’t be practical. There are some neighborhoods that are solidly Black but not to the proportion that would make me feel that we would need to go to the ward system.”24 While the local chapter of the Virginia Urban League offered their support, most of the local civil rights activists quoted in the sources I found offered a tepid “meh.”

This ambivalence towards wards by local civil rights activists has continued in more recent years. In 1992, as a city commission studied potentially bringing back the ward system, the local NAACP chapter again did not take a side on the question.25 When I was participating on the Alexandria elections panels, one of my fellow panelists, the current president of the Alexandria NAACP, was very cool to the idea of wards in Alexandria and did not appear to see them as a tool of fostering greater representation or correcting past injustices.

It’s worth mentioning that much of the coverage of the ward vs. at-large systems over the past few decades in the wider Alexandria area has focused on which political party would benefit the most from each system. In Arlington County, which borders Alexandria, the local Republican party chapter declared in 1986 that they were in favor of wards, while the local Democrat party chapter remained opposed. Journalists noted that Republicans tended to do better under ward systems.26 However, I’d be cautious to assign partisan politics as the only motivation to the current ward debate. While some of the ward supporters I’ve met are members of the Republican Party, others are Democrats, and several of the candidates competing in the city’s Democratic Council primary have also come out in favor of a ward system.27

A Ward to the wise, always do your research

It’s very possible that more documents might come to light in the future that will better help us understand the evolution of the local election system in Alexandria. If anyone reading this has any primary sources that challenge the account provided in the preceding paragraphs, please feel free to reach out with that info, and I’ll do a follow-up post. It does appear that at-large systems were used in other localities to limit the political power of historically underrepresented minorities, so we can’t full disregard the possibility that such a goal didn’t play a role in 1948. However, until more evidence comes up, we also shouldn’t accept that narrative unreservedly, especially since the available evidence seems to point to other factors driving the decision.

Personally, I don’t really consider myself either pro or anti ward at this point. I grew up in a city and later in a township that used wards for local elections, and they worked fine (the township was in a county that elected its commissioners through an at-large system, which also worked fine). While Alexandria has an at-large system, I’ve never had any trouble connecting with city council members to discuss local issues. I can see the potential value of having a ward system, but I am skeptical of some of the claims made by ward backers of what will happen if a such a system is adopted. Still, I’m open to being convinced strongly one way or the other. In the meantime, my hope is that as this city, or any locality, has policy discussions that involve the past, people make a real effort to do their research. Good history is a valuable part of creating good public policy, so it is worth it to get the facts straight, even if that means updating our historical understanding as new evidence comes to light.

Postscript

An interesting wrinkle in this story emerged after I hit “post.” I was reviewing the collections of the Arlington Historical Society (the county that borders Alexandria to the north) and came across this article about the history of their municipal elections. Among the revelations was that Arlington switched to an at-large system of voting (along with a county manager form of government) in 1930, two years before Alexandria switched back to a ward system for elections. In addition, unlike for Alexandria, there is some evidence that the at-large system was adopted with discriminatory intent. In 1974, George Vollin and Harrison Douglass, two long-time residents, testified as part of a lawsuit that Arlington officials began pushing for an at-large system after several Black residents announced their plans to run for office. According to their testimony, not only did county officials start agitating for at-large elections, but white residents, including the local KKK, conducted demonstrations and made threats in a coordinated effort to prevent Black residents from running for office and winning elections. While neither man was privy to the discussions of government officials, the timing of the demonstrations and the fact that their testimony was taken under oath means that their accounts cannot easily be dismissed out of hand.

So what does this mean for Alexandria? After all, the two jurisdictions shared a border. Many people living in Alexandria had friends and relatives living in Arlington and vice versa. Ultimately, it raises more questions than answers. For one, it's interesting that around the same time Arlington voters overwhelmingly voted for an at-large system, Alexandria voters voted to go back to wards. Jim Crow racism was present in both, yet they chose markedly different voting systems. The fact that Alexandria didn’t return to an at-large system until the late 1940s also limits what comparisons can be drawn to Arlington. Unlike the Arlington story, I couldn’t find any direct accounts from eyewitnesses who stated that the Alexandria 1948 referendum was motivated by a desire to limit Black political power. Of course, just because I couldn’t find a source doesn’t mean that it doesn’t exist. Alexandria has a large oral history collection, much of which is still inaccessible to researchers, and it’s possible that more insights may arise as more of the collection is made public. Still, this article about Arlington is an important reminder of the importance of keeping an open mind and being willing to take new information into account as it becomes available.

T. Michael Miller, Alexandria (Virginia) City Officialdom 1749-1992, (Bowie: Heritage Books, 1992), pg. vii.

William Hurd, “The City of Alexandria and Arlington County,” Alexandria History, Vol. 5, 1983, pg. 4.

Hurd, “The City of Alexandria and Arlington County,” pg. 5.

Hurd, “The city of Alexandria and Arlington County,” pg. 6.

Hurd, “The City of Alexandria and Arlington County,” pg. 8.

Beth Lawton, “Citizen Group Advocates for Return to Ward Representation in Alexandria,” Alexandria Living Magazine, April 20, 2021, https://alexandrialivingmagazine.com/news/for-wards-citizen-group-advocates-ward-representation-alexandria/

Preston M. Yancy, “It Seems to Me: Racist Attacks on the Crusade,” Baltimore Afro-American, July 26, 1969. [ProQuest Historical Newspapers]

Angelique Arintok, “Appeals court vacates decision that ruled Virginia Beach's at-large city council election system illegal,” 13NewsNow, July 27, 2022, https://www.13newsnow.com/article/news/politics/elections/appeals-court-throws-out-decision-virginia-beach-election-system-illegal/291-d87242bf-f3af-44d0-8653-6bb0984865c8 (Litigation on Virginia Beach’s election system is ongoing: https://www.wavy.com/news/local-news/virginia-beach/city-of-virginia-beach-responds-to-lawsuit-regarding-10-1-district-voting-system/)

1940 Census of Population: Volume 2. Characteristics of the Population. Sex, Age, Race, Nativity, Citizenship, Country of Birth of Foreign-born White, School Attendance, Years of School Completed, Employment Status, Class of Worker, Major Occupation Group, and Industry Group, Part 7: Utah- Wyoming, (Washington DC: Department of Commerce, 1943), pg. 169.

Negro Population, By County 1960 and 1950, (Department of Commerce Bureau of the Census, Washington DC, 1966), pg. 60 https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/decennial/1960/pc-s1-supplementary-reports/pc-s1-52.pdf; “

An Economic Summary of Alexandria, Virginia, (Charlottesville: University of Virginia, 1947), pg. 1. Found in the Papers of Armistead Boothe held at the Alexandria Library, Box 8, Folder 10.

Michael Pope, “Alexandria’s Failed Experiment with Wards,” Alexandria Gazette Packett, October 1, 2020, http://www.connectionnewspapers.com/news/2020/oct/01/alexandrias-failed-experiment-wards/

Brenda Mitchell-Powell, Public in Name Only: The 1939 Alexandria Library Sit-In Demonstration, (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2022), pg. 155.

James Hershman, "Armistead L. Boothe (1907–1990)" Encyclopedia Virginia. December 7, 2020, https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/boothe-armistead-l-1907-1990/

“Anti-Jim Crow Bills Puzzle Alexandria,” The Washington Daily News, February 7, 1950. Found in the Papers of Armistead Boothe held at the Alexandria Library, Box 8, Folder 5.

“Third District Omegas Commend Truman, Boothe” Norfolk Journal and Guide, May 20, 1950. Found in the Papers of Armistead Boothe held at the Alexandria Library, Box 8, Folder 12.

“Hicks, Squires to Campaign in Alexandria,” The Washington Post, February 21, 1948. [ProQuest Historical Newspapers]

“Bryan Urges Redistricting in Alexandria,” The Washington Post, June 24, 1944. [ProQuest Historical Newspapers]

Michael Pope, “Alexandria’s Failed Experiment with Wards,” Alexandria Gazette Packett, October 1, 2020, http://www.connectionnewspapers.com/news/2020/oct/01/alexandrias-failed-experiment-wards/; Richard Lyons, “Campaign Starts on Ward, at-Large Election Issue,” The Washington Post, February 15, 1948. [ProQuest Historical Newspapers]

William H. Smith, “Fight Flares on Colonsanto,” The Washington Post, November 9, 1947. [ProQuest Historical Newspapers]; “Favors Referendum on Choosing Council Members at Large,” The Washington Post, January 29, 1948. [ProQuest Historical Newspapers]

Michael Pope, “The Hidden History of Del Ray,” Connection Newspapers, March 22, 2019, http://www.connectionnewspapers.com/news/2019/mar/22/hidden-history-del-ray/

“Charter Amending Bill Stirs Battle,” The Washington Post, January 16, 1932. [ProQuest Historical Newspapers]

Michael Marriott, “N. Va. Blacks Differ on Election by Ward,” The Washington Post, June 23, 1983. [ProQuest Historical Newspapers]

Marriott, “N. Va. Blacks Differ on Election.” [ProQuest Historical Newspapers]

Peter Y. Hong, “Wards Considered in Alexandria,” The Washington Post, December 31, 1992. [ProQuest Historical Newspapers]

Leah Y. Latimer, “Va. Voting Rights Suits Boost Black Influence,” The Washington Post, September 8, 1986. [ProQuest Historical Newspapers]

Teo Armus, “A guide to the 2024 Alexandria Democratic primary election,” The Washington Post, May 4, 2024, https://www.washingtonpost.com/dc-md-va/2024/05/04/alexandria-2024-democratic-primary-election-voter-guide/